RT en Español: How Russian Disinformation Targets 500 Million Spanish Speakers

Daniel Iriarte

[This article is part of our publication project “RT in Europe and beyond”]

If readers are interested in current Russian affairs, they may be familiar with the dramatic transformation of Russia Today in the last years of the previous decade. Launched in 2005 as a mostly benign channel to present Russia in a positive light for English-speaking viewers, it became nonetheless a tool of Moscow’s propaganda during the Georgia war in 2008. The transformation of Russia’s information war doctrine in those years, fuelled by this conflict, led Russia Today not only to be renamed as RT, but also to become the spearhead of Russian state disinformation. But the Kremlin decided not only to put the media it controlled at the service of its goals; it would also go global.

For this reason, RT transmissions in the Spanish language started 24/7 in December 2009 after a short trial period. The fact that RT en Español (its official name in Spanish) was the third language-oriented channel of the network after English and Arabic – and many years before its versions in German and French – gives an idea of the importance that Russia gives to Spanish-speaking audiences, a result of its growing involvement in Latin America. And certainly, Spanish is the fourth most spoken language in the world: it is the mother tongue of 493 million people, including 42 million only in the US. If we include those who have some knowledge of the language, the figure grows to 591 million all over the world.1

As a general rule on Russian propaganda, the closer a topic to the Kremlin’s core interests is, the stronger the disinformation. In this regard, for a casual observer, RT en Español may resemble a relatively serious TV channel reporting on international affairs – as long as it does not address subjects like Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, the status of the Crimean Peninsula or the war in Syria. By focusing mostly on Latin America, its news programs may seem merely informative, although with a marked ideological bias. This last feature does not stand out in the hyper-partisan Hispanic media ecosystem, however, as it is often assumed that every outlet has an ideology, and audiences know what to expect from it. And in contrast to editions of RT in other languages – such as English, French or German – that have a more ambiguous political stance and can appeal both to the left-wing and the right-wing fringes, Spanish RT has a very clear target audience: left-wing viewers, especially those of the so-called “Bolivarian Left”, which had a strong weight in progressive Western circles in the two previous decades and remains significant in Latin America and, to a lesser extent, in Spain.

Nonetheless, as Russia’s geopolitical outreach has expanded in Latin America – mostly in relation to its alliance with the Venezuelan government – so has Russian disinformation done on local issues. This is very visible in the Spanish version of RT.

In January 2020, the U.S. Department of State established that Russia was very active in spreading disinformation in South America against the members of the so-called Lima Group, the alliance of countries opposed to Nicolás Maduro’s regime.2 According to our own observations, this estimation is correct, as conservative governments in the region are constantly targeted by negative reporting in Spanish-language editions of Russian state-sponsored outlets (Sputnik, NewsFront), if not by outright fabrications. In this scheme, RT en Español serves to generate mass content that is then replicated via social media, often with misleading headlines or biased commentaries.

Maximizing the impact of RT en Español

The audiences of Spanish RT’s traditional broadcasting are negligible, and do not reach even the 0.1 percent of the share needed to be reported by Spain’s statistical institutions. However, it has other ways to spread its content, through small cable and satellite TV providers in Spain and Latin America, and partnerships or associations with other channels. Some 70 local or national TV stations fill spaces with RT content, and the company claims to be present in 315 hotels. Several Cuban and Venezuelan channels also transmit Spanish RT for a few hours a day.

In April 2018, RT en Español claimed its audience to have grown 36 percent all over the world since 2015, reaching 18 million people and tripling its audience in Latin America, especially in Mexico, thanks to an agreement to include the channel on one of the main satellite platforms.3 Since then, these figures kept growing. On 28 December 2019, RT broadcast a special programme to celebrate its 10th anniversary.4 The programme claimed that the channel reached an audience of 20 million people in Latin America alone. This growth was fuelled by its own investment in cooperation and expansion. For example, the number of satellite and cable TV networks transmitting RT in Latin America, Spain and the US rose from 660 to over 1,000.5

It is hard to verify these figures independently. However, social media and Internet monitoring can provide a more objective indicator of its impact. In October 2021, the number of followers of RT en Español was over 3.2 million on Twitter and over 18.1 million on Facebook. Its YouTube channel had 5.35 million subscribers and had reached almost 4 billion plays. A SimilarWeb analysis shows that the RT en Español website reached 19.32 million views in September 2021, with almost half of its traffic coming from Venezuela, Mexico, Argentina and Colombia, plus another 11.1% coming from Spain.6

And it is on social media where RT has a real impact. RT en Español has the capacity to produce a huge amount of content that is then spread and amplified by a network of accounts, especially on Facebook, the most popular social network in Latin America. This has been evident in times of crisis, such as the massive protests and riots in Ecuador (2019), Chile (2019-2020) or Colombia (2021), where the content produced by RT about police violence against demonstrators – in some cases filling an informative vacuum – were widely shared on social media and contributed to further inflaming the situation.

Yet another remarkable element about RT’s influence is the fact that many medium to low sized Latin American and Spanish media use them as a legitimate source – in the same way as, for example, BBC or Al Jazeera – for their coverage of international affairs. As many of those media do not have a proper budget for international reporters, correspondents on the ground or special envoys, their international news desks rely on bigger outlets to gather the facts on global events. And as they include RT among these outlets, this situation heavily influences the reporting on critical issues, such as Russia’s relations with other countries like the US, or the wars in Ukraine and Syria.

Who makes RT en Español?

While in January 2017 most of the work was done in Moscow, Montevideo and Madrid, the channel has since opened its own studios in Buenos Aires, Mexico City and Miami. Besides, it can count on the network of RT English studios in places like Washington or London, which are used to report from those cities whenever necessary. It also has correspondents in Caracas and Havana, among other places.

At the moment of writing, according to its own website, the crew of visible faces on RT en Español is composed of five Russians, five Spaniards, five Argentinians, five Mexicans, four Chileans, three Ecuadorians, two Venezuelans, two Cubans and one US citizen; they are anchormen and anchorwomen, presenters of different TV shows or correspondents and journalists who appear on camera.7 In addition to them, there is a multinational team of several dozen people in charge of production, writing and technical work.

The director is another Russian, Victoria Vorontsova. According to her LinkedIn profile,8 she studied Spanish language and culture in Madrid in 1997 and Science, International Relations and Law in Northern Iowa the following year, complemented with a Master degree in International Relations in Moscow. She has been part of the RT team since 2005, first as a news editor and then as an adviser to the editor-in-chief. When RT en Español was created in 2009, she was immediately appointed to head it. However, she does not have a strong public profile. She has only 3,680 Twitter followers at the moment of this research, and her Twitter and Facebook accounts are mostly devoted to retweeting RT content.

But the most interesting figure in the leadership of RT Spanish is the deputy director of the website, Inna Afinogenova. Over the past five years, she has become a highly influential YouTube star thanks to her ironic/humoristic political clips that were first broadcast during the news shows of RT en Español but then became an independent programme, called “Ahí les va” (an expression that can be translated as “Here you have it”). It first appeared on YouTube and is now be found on the RT website. Through humour, irony and “whataboutism” (an old technique mastered by Soviet diplomats, consisting in pointing to the flaws of others as a way to defend oneself from criticism), “Ahí Les Va” promotes subtle yet highly manipulative narratives about international politics, mostly – but not only – covering Latin American affairs. The underlying philosophy of the programme, repeated almost verbatim on most shows, is “Mainstream media are hiding/not showing/manipulating information on current affairs, but thankfully we are here to explain it to you”.

Afinogenova’s command of the Spanish language is impressive, and the jokes are usually pretty funny, so it is not strange that the programme is a wild success among Latin American audiences. Its outreach should not be underestimated: at the time of this writing, Afinogenova’s YouTube channel has almost 1 million subscribers, a massive increase from the 184,000 it had in February 2020. Her Telegram channel is followed by more than 54,500 people. Most videos reached over 200,000 views, with those addressing the protest and instability wave in Latin America reaching around 300,000 views. An explainer of the crack in Chile’s social, capitalist model, which has been viewed by more than 600,000 people, remains the most viewed clip so far. Several videos about alleged campaigns against the Sputnik V vaccine reached more than half a million views, while most videos about Colombia reached more than 400,000 views.

What viewers see on RT en Español

RT programming is not as diverse as it may seem at first sight. It includes many documentaries, usually related to Russian weapons or some aspects about life in Russia’s regions, as well as social issues in different parts of the world. RT en Español also has sports, travel and interview programmes. News shows are constant, broadcast on almost an hourly basis from 1 pm to 5 am.

But the most important feature of the channel is its political shows, such as “RT Reporta” (“RT Reports”), in which RT journalists address current affairs all over the world and interview experts and figures relevant to the subject. While the characteristics of the show resemble objective journalism, the choice of topics is never accidental, often highlighting the uglier aspects of Western societies or Latin American countries ruled by right-wing governments. Another programme, “En la mira” (“In the crosshairs”), is a monthly partnership between RT en Español and Venezuelan state TV channel Telesur, aiming to present Venezuela and other allied nations such as Cuba or Bolivia as the permanent target of the capitalist West, which attacks their sovereignty.

A few years ago, English RT broadcast a much-discussed show hosted by Julian Assange, in which the founder of Wikileaks interviewed figures ranging from Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah to former Guantanamo prisoners to Malaysian politician Anwar Ibrahim. Similarly, from March 2018 to June 2020, RT en Español had a show titled “Conversando con Correa” (“Talking with Correa”), in which the former Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa interviewed leading progressive international figures. They were mostly from Spain and Latin America, such as Pablo Iglesias Turrión, the co-founder and and former Secretary General of the Spanish far-left party Podemos, and Guatemalan Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú, but there were also renowned intellectuals, activists and politicians from other countries, such as UN human rights adviser Jean Ziegler, lawyer and journalist Glenn Greenwald, filmmaker Oliver Stone, musician Roger Waters and former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Some of them even appeared in both Assange and Correa’s shows, such as U.S. intellectual Noam Chomsky.

Although some of the guests are certainly controversial, such as former Catalan president Carles Puigdemont (now a fugitive from Spanish justice), “Conversando con Correa” is mostly a talk show where two strong personalities – the interviewee and Correa himself – exchange views on current or cultural affairs. For this reason, and given the unequivocal ideological stance of its high-profile participants, it is rather harmless and definitely inside the limits of the freedom of expression. But the programme is significant for another reason: it shows the commitment of RT en Español to the political movement of Correa, currently exiled in Brussels after being sentenced in absentia to eight years of prison on corruption charges. Correa’s supporters claim that these charges are fabricated, and Interpol has repeatedly refused to enforce a Red Notice against him on the grounds that it was politically motivated. Ecuador’s former president hopes that a more sympathetic government may pave the way for his return to the country as a free man. For this reason, RT and other Spanish-language Russian state-sponsored outlets devoted enormous efforts to promote the candidacy of Correa’s heir, Andrés Arauz, in the 2021 general election. Although Arauz was ultimately defeated in the run-off by conservative candidate Guillermo Lasso, RT is currently working to undermine the latter’s presidency, accusing him of not having fulfilled his electoral promises despite having been in power for only four months, and suggesting that Lasso’s government may be promoting the recent wave of prison riots to set grounds for a security referendum that would allow the return of U.S. military bases to the country.

Another interesting show, still being broadcast, is “Detrás de la noticia” (“Behind the news”), hosted by Eva Golinger. This Venezuelan-U.S. lawyer and activist became a celebrity within progressive circles after the publication of her 2006 book The Chávez Code,9 which, on the basis of U.S. official documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, claimed to prove Washington’s involvement in the 2002 failed coup d’etat against Venezuelan then-president Hugo Chávez. For some years, Golinger became an informal advisor and advocate for Chávez’s government.10 She reflected on her experiences in her 2019 book Confidante of ‘Tyrants’: The Story of the US Woman Trusted by the U.S.’s Biggest Enemies.11

In every episode of “Detrás de la noticia”, Golinger addresses topics that concern U.S. and Latin American progressives, such as immigration, environmental issues, gun proliferation, inequality or U.S. interventionism abroad, with a striking tolerance towards left-wing governments no matter how authoritarian they are (as, for example, the Cuban or Venezuelan regimes), always portrayed as victims of imperialism. The longevity of the programme, which started in January 2011, is remarkable, as it promotes many of the core topics of RT, such as an image of the U.S. as an unfair, dysfunctional and basically evil state. Compared to such a human rights violator, the narrative seems to go, Russia does not look so bad. However, it would be wrong to consider Golinger a Kremlin employee or outright propagandist: as a prominent activist on her own, she rather fits the category of those who for ideological affinity, anti-imperialist conviction or mere disorientation can be labelled “RT’s fellow travellers”.

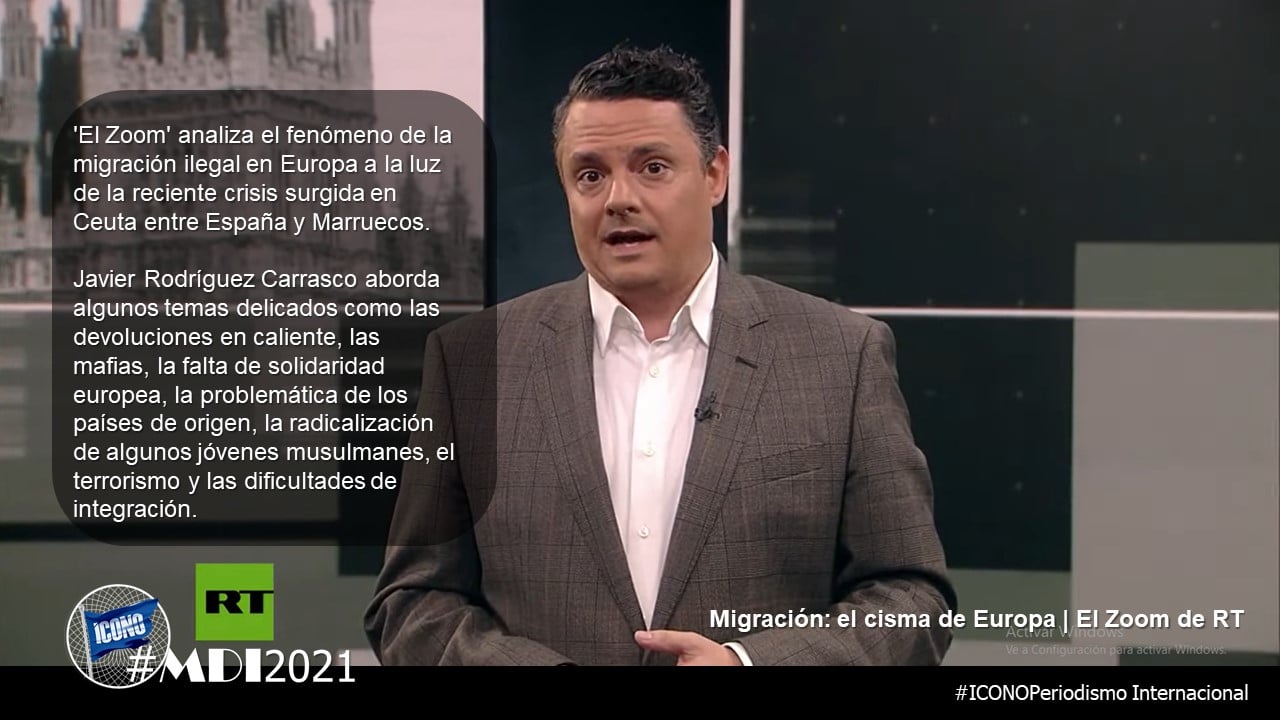

But the true star of the channel is the TV show “El Zoom” (“The Zoom”), a supposedly analytical yet highly manipulative programme in which the presenter addresses current affairs twice a week with the help of some guests. And make no mistake: the topic is always in a top position in the Kremlin’s interests list, be it gas supplies to Europe, naval incidents with NATO warships in the Black Sea or political crises in the Latin American countries, the governments of which Moscow aims to weaken. The show serves for its presenter, Spanish journalist Javier Rodríguez Carrasco – who has been working for RT en Español practically since its foundation in 2009 – to introduce a series of strategic narratives, permanently in the service of Russia’s propagandistic framework. He launches these ideas amid long commentaries, sometimes before asking the interviewees about a totally different issue. This way, these strategic messages (for example, “we all know that the U.S. backs Al Qaeda and the Islamic State”, “the EU is weak and on the verge of collapse”, “the U.S. always betrays its partners because it wants vassals, not allies”, “Navalny and the Russian opposition are stooges of Western intelligence services”) remain uncontested. In general, guests are already sympathetic to these points of view, but in the rare occasions that they are not, or if they dare to challenge an argument expressed by the presenter, Rodríguez Carrasco simply changes the subject and asks a different guest about another topic. Thus, many participants never realise how they are played by this experienced host.

Disinformation campaigns: the case of @spainbuca

RT en Español has played a prominent role in different centralised disinformation campaigns. Probably the most important was the operation unleashed after the downing of the MH17 Malaysia Airlines flight over Ukraine in July 2014. In the hours immediately after the incident, a team from RT en Español, which was on a reporting trip to Donbass, travelled to the place and filmed the wrecked fuselage, while expressing a notorious ambiguity about who was responsible for the downing. More importantly, an alleged Spanish air controller with a Twitter handle @spainbuca, who claimed to be in the control tower of the Boryspil Airport in Kyiv, started tweeting about the alleged presence of two Ukrainian warplanes in the area, among other elements that suggested that Ukraine was behind the incident and was attempting to cover it up. Soon after, “he” disappeared from the public view and “his” account was cancelled by Twitter, leading some internauts with pro-Kremlin views to wonder if he had been “silenced for knowing too much”.

@spainbuca had already made an appearance on RT en Español months before under the same identity, an alleged Spanish air controller named “Carlos” who “had been living in Ukraine for five years”. In an interview with RT news show in May 2014, he claimed to have been forced to leave Kyiv after receiving death threats for his posts on social media criticising the Maidan “coup”.12 Neither of these two interventions was genuine: in 2018, a joint investigation by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Romanian site RISE Project revealed that his real identity was José Carlos Barrios Sánchez, and that he was a conman arrested for fraud in Romania in 2013.13 He had never been an air controller in Ukraine, where, in fact, it had already been established that there were no Spaniards in such a role. In a recorded phone interview with the investigative journalists who exposed him – which the author of this chapter was able to obtain independently – Barrios Sánchez claimed that for his interventions he had received significant amounts of money from the RT team, who told him what he had to say.14

This flagrant falsity was nonetheless widely exploited by Russian disinformation and diplomacy, until it became impossible to continue with the farce. Even Vladimir Putin, in his interviews with U.S. filmmaker Oliver Stone, made a reference to the “specialist of Spanish origin” who exposed “Ukraine’s military aircraft in the corridor assigned for civilian aircraft”.15 And in the years that have passed since this episode, RT en Español has continued spreading different Russian versions of the downing of the MH17 flight, trying to convince its audience that Russia bore no responsibility for the incident and that the international investigation had no interest in uncovering the truth, only in falsely blaming Moscow for the downing.

Other disinformation operations in which RT en Español played a key role are the amplification of Catalonia’s pro-independence movement in the last months of 2017. Although the coverage of the irregular independence referendum organised by pro-independence Catalan authorities was presented as factual and as an attempt to “give voice to both sides”, it usually ignored that the consultation was illegitimate in the eyes of the Spanish authorities and was not recognised by any transnational body or legitimised by international observers. Exaggerations and decontextualised data were a common feature on RT in that period, and when counter-riot policemen sent to prevent the celebration of the referendum beat up voters in front of the cameras, the images – and the reactions to them – were exploited by RT for a whole week. Significantly, the consultation and police repression in Catalonia were not covered on the ground by the usual local correspondents (all of them Spaniards), but by an Argentinian reporter who was sent from Moscow to Barcelona.

And this is, very often, the way that RT en Español serves a wider disinformation framework: in many cases, it does not invent falsities or conspiracy theories, which could be easily disproven and would quickly discredit the TV channel. Instead, it identifies highly controversial topics and amplifies them under the mask of “critical journalism”, usually focusing on their most divisive aspects. This is what RT France did with the Yellow Vest movements16 and what RT Deutsch did with the so-called “Querdenken” movement protesting against COVID-19 policies.17 Besides Catalonia, RT en Español used this same strategy, for example, with the incarceration of rapper Pablo Hasél in February 2021 for the crimes of “praising terrorism” and “insulting the Crown” in his lyrics.18

The Hasél case is complicated and controversial, and many human rights defenders, including Amnesty International, have called to abolish the legislation that led to his imprisonment. However, he had also been previously sentenced for a crime of aggression against a policeman, so as a convicted felon he had to go to prison after being found guilty of this second series of charges. RT, as one could expect, not only failed to explain the nuances of the case, but also compared it unfavourably to the alleged tolerance showed by Spanish authorities towards a neo-Nazi march that took place in Madrid in these same days.19

Targeting Latin America

The same modus operandi has been successfully applied in Latin America. Social upheavals in the region have multiple causes, so attempting to blame protests on “Russian interference”, as some officials tried to do,20 sounds ridiculous (and indeed helps to reinforce the narrative that “Russia is always falsely accused”, as Russian propaganda dutifully reiterates at any opportunity). However, there is a large body of evidence showing that when these sorts of upheavals take place, Russia’s propaganda machine is well placed to exploit and amplify them, and it does.21 By siding with the protesters, whose demands are seen as legitimate by wide sections of the population, RT manages to establish itself as a credible source, unlike pro-government media that are perceived as biased.

As a result, the audiences of RT en Español have grown exponentially in these years, peaking during periods of instability in these countries. During the two most intense weeks of the protests in Chile in 2019, RT en Español entered the ninth position in the ranking both of the most influential media and most shared content in the country, according to a social media analysis of the private Spanish firm Alto Analytics commissioned by the Chilean government.22 When riots exploded in Colombia in April 2021, RT en Español ran dozens of stories and videos about police violence and repression against demonstrators. As the protests were not initially covered by international media, these materials filled an information vacuum and became viral immediately, also helping to fuel discontent against Colombian authorities. Previously, in face of a similar context in November 2019, the government of Ecuador cut off the broadcasting of RT en Español and Venezuela’s Telesur on the basis that they were contributing to inflame the situation.23

Interestingly, in contrast to other editions of this channel, RT en Español did not contribute much to spread coronavirus disinformation or anti-vaccination narratives, according to a July 2020 analysis by the Stanford Internet Observatory.24 “A study of Russian disinformation across the six languages covered by RT suggests that RT en Español is, unlike other RT outlets, not a primary vector for influence operations; instead, Russia-aligned disinformation is funnelled into Spanish-speaking communities through other ‘grey’ propaganda channels”, the report states.25 The reasons are unclear, but we can speculate that progressive audiences in Latin America and Spain, the target audience of RT en Español, tend to be much more pro-science and pro-vaccine than their counterparts on the Right. Instead, RT en Español focused strongly on promoting the virtues of the Sputnik V vaccine and denouncing “international campaigns” against it.26 When Sputnik V was launched, several Latin American governments like Argentina and Mexico immediately showed interest in purchasing it. Since Moscow was trying to use the vaccine as a vehicle for influence in the region, spreading anti-vaccination narratives would have been a shot in the foot. Whatever the motives, independent observers including the author of this article soon noticed that any information related to the Sputnik V was shared many thousands of times on social media, when other articles were usually shared only in the dozens or in the hundreds at most. Whether this was partially the result of a coordinated campaign has never been properly determined, but we can be sure that the interest of Spanish-speaking audiences in the Sputnik V was genuine.

But RT en Español does not hesitate to resort to conspiracy theories or outright lies when necessary to promote a “higher cause”. In recent months, for example, it has spread the idea – of course, without proper evidence – that the U.S. and Colombian authorities are somehow behind the murder of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse,27 or that the government of Guillermo Lasso is deliberately promoting the wave of prison riots in Ecuador28 in order to boost a referendum on national security that would allow the return of U.S. bases to the country.29

These techniques could backfire, though: as disinformation gains more prominence in the contents of RT en Español, an increasing number of citizens realises its true nature. It is interesting that, unlike in the early years of the channel, not many reputed Spanish academics agree to be interviewed in RT programmes today, as many of them are wary of past distortions. Unfortunately, this is not the case yet in Latin America, where many real experts still contribute happily to the channel’s shows. However, judging by reactions on social media to RT articles and shows, awareness about these manipulations is growing too. As the channel adopts an increasingly biased approach and its falsifications become apparent to more people, also grows the number of those who can experience first-hand how unreliable RT en Español is, and how its real goals are not to make information public but to lead its viewers to see the world the way the Kremlin wants. Luckily for all, this can only work for so long before one is confronted with reality.

Endnotes

1. Cervantes Institute yearly report on the situation of the Spanish language in the world: “El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2021”, Instituto Cervantes, October (2021), https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/anuario/anuario_21/informes_ic/p01.htm.

2. Lara Jakes, “As Protests in South America Surged, So Did Russian Trolls on Twitter, U.S. Finds”, The New York Times, 19 January (2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/19/us/politics/south-america-russian-twitter.html.

3. “La audiencia televisiva de RT se triplica en Latinoamérica y alcanza los 18 millones de personas”, RT en Español, 3 April (2018), https://actualidad.rt.com/actualidad/267339-ipsos-audiencia-televisiva-rt-crece.

4. “10 años de RT en Español con una millonaria audiencia creciendo”, RT en Español, 28 December (2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQMfMk5T6Zg.

5. “Quiénes somos”, RT en Español, https://actualidad.rt.com/acerca/quienes_somos.

6. “actualidad.rt.com”, SimilarWeb, https://www.similarweb.com/website/actualidad.rt.com/.

7. “Equipo de RT”, RT en Español, https://actualidad.rt.com/acerca/equipo.

8. “Victoria Vorontsova”, LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/in/victoria-vorontsova-059299a.

9. Eva Golinger, The Chávez Code: Cracking U.S. intervention in Venezuela (London: Pluto Press, 2006).

10. The Guardian’s former correspondent in Venezuela included an interesting profile of Golinger in his book on Hugo Chávez, see Rory Carroll, Comandante: Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela (New York: Penguin Press, 2013).

11. Eva Golinger, Confidante of Tyrants: The Story of the U.S. Woman Trusted by the U.S.’s Biggest Enemies (La Vergne: New Internationalist, 2019).

12. The interview is still available online: “Amenazan de muerte a un español en Ucrania por opinar sobre la crisis”, YouTube, 8 May (2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wev4riOHtmc.

13. Carl Schreck, Ana Poenariu, “Catch Carlos if you can”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 14 March (2018), https://www.rferl.org/a/catch-carlos-if-you-can-mh17-russia-ukraine/29065244.html.

14. According to a media source, the total amount was USD 48,000. See Pablo Mediavilla Costa, “Desenmascarado ‘Carlos, el falso controlador aéreo español que esparció mentiras sobre el derribo del MH17”, Vanity Fair, 17 March (2018), https://www.revistavanityfair.es/poder/articulos/carlos-spainbuca-controlador-aereo-propaganda-mh17-putin/29751.

15. Oliver Stone, The Putin Interviews: Oliver Stone Interviews Vladimir Putin (Skyhorse Publishing, 2017).

16. Colin Gérard, Guilhem Marotte, Loqman Salamatian, “RT, Sputnik et le mouvement des Gilets jaunes: cartographie des communautés politiques sur Twitter”, L’Espace Politique, 20 October (2020), https://journals.openedition.org/espacepolitique/8092.

17. Maik Baumgärtner, Roman Höfner, Ann-Katrin Müller, “Germany Fears Influence of Russian Propaganda Channel”, Der Spiegel, 3 March (2021), https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/rt-germany-berlin-fears-growing-influence-of-russian-propaganda-platform-a-b62cb977-fc1a-4d66-8c7c-9859d8d00315.

18. See, for example: “¿’Democracia plena’? Cárcel para el rapero Pablo Hasél y permiso para marcha nazi en España”, Ahí Les Va, 19 February (2021), https://www.ahilesva.info/60524ba9dc76de187771ebea.

19. The neo-Nazi gathering, in which speakers made anti-Semitic speeches with statements such as “The Jew is guilty!”, became a scandal after Russian video agency Ruptly filmed it and passed the images on to a left-wing Spanish publication. The speakers at the event immediately became the subject of a judicial investigation for possible hate crimes, but this was deliberately ignored by these same Russian outlets, as it contradicted their narrative about a “Nazi-friendly Spanish government”.

20. “Russia Was Involved in Online Attacks During Protests, Ecuador Official Says”, The Moscow Times, 18 October (2019), https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/10/18/russia-was-involved-online-attacks-during-protestsecuador-official-says-a67790; David Alandete, “Ecuador y Bolivia tratan de frenar la propaganda rusa”, ABC, 1 December (2019), https://www.abc.es/internacional/abci-ecuador-y-bolivia-tratan-frenar-propaganda-rusa-201912010204_noticia.html; “Rusia rechaza estar tras ataques cibernéticos contra Colombia”, Deutsche Welle en Español, 22 May (2021), https://www.dw.com/es/rusia-rechaza-estar-tras-ataques-cibern%C3%A9ticos-contra-colombia/a-57628466 .

21. See, for example, “Measuring the Impact of Misinformation, Disinformation, and Propaganda in Latin America”, a joint report by Global Americans (New York, United States), Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo de América Latina (CADAL, Buenos Aires, Argentina), Medianálisis (Caracas, Venezuela), Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (Monterrey, Mexico), and Universidad del Rosario (Bogotá, Colombia), 28 October (2021), https://theglobalamericans.org/monitoring-foreign-disinformation-in-latin-america/.

22. The report was available online for some time on the website of Alto Analytics, although it disappeared when this firm changed its name to Constella Intelligence. A summary of its content (in Spanish) can be consulted here in Eduardo Olivares, Francisca Vargas, “El verdadero informe big data de Alto Analytics sobre la crisis chilena”, Pauta, 16 February (2020), https://www.pauta.cl/nacional/verdadero-estudio-alto-analytics-redes-sociales-crisis-2019-chile-colombia. I was able to review a printed version of the original report.

23. “Ecuador Cuts off RT Spanish Broadcast without Explanation Following Minister’s Complaint about Protest Coverage”, RT English, 15 November (2019), https://www.rt.com/news/473584-ecuador-cut-off-broadcast-rt/.

24. Daniel Bush, “Two Faces of Russian Information Operations: Coronavirus Coverage in Spanish”, Stanford Internet Observatory, 30 July (2020), https://fsi.stanford.edu/news/two-faces-russian-information-operations-coronavirus-coverage-spanish.

25. Ibid. This statement is, however, not entirely accurate. According to our own observations, disinformation targeting Western vaccines had a strong presence in RT en Español throughout 2020 and 2021, mostly through misleading headlines about dangerous side effects, even when the article itself clarified that these effects were not necessarily a result of the vaccine.

26. “Pro-Kremlin Media as a Marketing Tool: Promoting Sputnik V Vaccine in Latin America”, EUvsDisinfo, 4 December (2020), https://euvsdisinfo.eu/pro-kremlin-media-as-a-marketing-tool-promoting-sputnik-v-vaccine-in-latin-america/.

27. RT devoted no less than two episodes of “El Zoom” to this idea, see “Haití: caos in final” [“Haiti: unending chaos”], RT en Español, 9 July (2021), https://actualidad.rt.com/programas/zoom/397379-haiti-caos-sin-final; “Haití: crimen organizado” [“Haiti: organized crime”], RT en Español, 16 July (2021), https://actualidad.rt.com/programas/zoom/397978-haiti-crimen-organizado.

28. See “Masacre carcelaria en Ecuador: ¿quién controla las prisiones en el país (y quién lo permite)?”, Ahí Les Va, 8 October (2021), https://www.ahilesva.info/6160a303dc76de08e10f6cb9.

29. In 2009, Rafael Correa refused to renew the agreement that allowed the Pentagon to use the military air base of Manta. In 2014, all remaining US military personnel was expelled from Ecuador, see “Ecuador expels US military staff”, Associated Press, 25 April (2014), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/25/ecuador-expels-us-military-attaches.