Ambitious Goals and Modest Results: RT UK and Its Coverage of the 2019 British General Elections

Vitaly Kazakov

[This article is part of our publication project “RT in Europe and beyond”]

Introduction

Like other arms of Russia Today (RT)’s network, RT UK has had a short yet volatile history.1 The British branch of the Russian state-sponsored broadcaster was created in 2014 with a view to “challenge dominant power structures in Britain by broadcasting live and original programming with a progressive UK focus”.2 The launch for the new UK channel was indeed ambitious in terms of the resources committed and objectives posed. Recording and broadcasting daily news bulletins and special programming from its lavish central London studio, RT UK became accessible to most UK households through several terrestrial and satellite TV channels, as well as via new media platforms. Its newly assembled journalistic and production cast was aiming to “do what statutory regulators are supposed to do – hold power to account”.3

Over the years of its activity, RT UK (and its parent network, RT International) became an object of scrutiny by both the British political establishment and the media regulators. The activities and outputs of the wider RT network, and of RT UK specifically, have been at the centre of several high-profile political scandals and investigations conducted by the UK Office of Communications (Ofcom), which is responsible for monitoring media networks’ compliance with national broadcasting regulations. A range of high-profile British politicians have also accused the network of being a “weapon of (Russia-sponsored) disinformation”.4 In July 2021, RT ceased the production and broadcasting of daily UK-specific news bulletins; RT UK continued to work only on its special programmes and online content.

The end of RT’s UK-focused news production was undoubtedly a blow to the broadcaster’s initial vision for entering the British news media field and being a competitor therein. The history of RT UK presents a unique case for the efficacy of international efforts in influencing information. As a branch of the RT information network, RT UK shares some characteristics with its partner RT channels, such as language (i.e., creating content in English alongside RT International and RT America) and a comparatively narrow national focus (similar to RT America and, to some extent, RT France and RT DE). This chapter aims to provide an overview of some of the factors that shaped features of RT UK operations, its programming, reach, and audience reaction. I will also present some highlights from my case study on the channel’s coverage of the 2019 UK General Election across its programmes and media platforms – this will assist in forming a clearer picture of RT UK and will contribute to some of the current debates concerning this channel.

Programming overview

To match the new network’s ambition of shaking up the established news media environment in the UK, RT UK produced a broad range of programmes via TV broadcasts and through its online channels. One of its key elements were the daily news bulletins (approximately 25-30 minutes long) that aired hourly on weekday evenings. Alongside a full range of RT-produced programming, the bulletins were made available to up to 90 percent of all UK households via Freeview and several satellite channels.5 Prior to the cancellation of its TV news production, RT UK’s daily bulletins covered a variety of local and international topics “that mattered most to Britons”.6 The bulletins were also live-streamed and available to the British and international audiences via RT UK’s dedicated YouTube and Facebook channels, as well as the network’s website. As of the summer of 2021, the RT UK YouTube channel had over 210,000 subscribers; it was still lagging severely behind its sister channels, RT Arabic and RT en Español, which had over 5 million subscribers each. In terms of subscriber numbers, RT UK’s Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram accounts (which also share select news clips in addition to other content) also significantly trail behind their counterpart RT channels as well as other major international media outlets’ accounts. Despite that, these online platforms allowed RT UK’s news content to find some audiences; for example, several of RT UK’s YouTube clips have been viewed more than two million times.7

In addition to its news programmes, RT produced several TV shows featuring a mixture of high-profile and controversial presenters and political personalities. These included the former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond, who hosted his own political discussion show.8 From the outset, Salmond’s employment with RT caused some disquiet in mainstream British media;9 the notorious legal proceedings he was involved in, and the controversy in the wake of the “Russia report”10 will be discussed in more detail below. Another controversial politician-turned-RT UK show host is George Galloway, a former left-wing MP, who was attempting to make a return to parliament.11 He hosted a TV talk-show Sputnik,12 and regularly contributed opinion pieces to the RT’s news website. Securing the services of Salmond and Galloway for its UK programming furthered RT International’s wider strategy of employing “prominent figures at the political margins”, in order to help the network to cover “‘inconvenient’ stories that the ‘mainstream media’ overlook”. It de-emphasizes [RT’s] affiliation to the Russian perspective, and presents itself as the voice of a “transnational anti-imperialist movement”.13 Neither Salmond nor Galloway had obvious links with, or interest in, Russian affairs prior to their RT employment. RT UK’s selection of these two prominent – and controversial – Scottish politicians, who often endorse polarising views as its flagship programmes’ hosts, demonstrates the channel’s interest in exploiting social and political cleavages within British society (such as debates surrounding Scottish independence, and Brexit).14

In addition to such politicians, RT UK became home to several British journalists, including Afshin Rattansi, who previously worked for The Guardian, BBC, Channel 4, and Bloomberg TV.15 His show Going Underground was another long-running RT UK programme, and featured analyses of recent news and developments, and interviews with a range of guests – the aim was to “discover the stories that aren’t being covered by the mainstream UK media”.16 This is an example of what has been referred to as “media-centricity” within the wider RT approach to news coverage, or a strategy designed to present a story through the lens of how other outlets often inadequately report on the issue in question.17 This approach was clearly adopted by RT UK across all its programming. Where some of RT International’s flagship TV shows are often provocative and one-sided in terms of their discussion of controversial international developments, RT UK’s Going Underground has been observed to draw on a pool of more “widely-recognised expertise and more varied opinion” whilst still adhering to the overarching positions and themes prevalent in RT’s reporting.18

Until 2018, RT UK hosted a satirical news discussion programme, Sam Delaney’s News Thing,19 which was similar in its tone and approach to more mainstream late-night shows on Western TV networks. RT UK’s staff also included Polly Boiko, a presenter who hosted a show ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), which was specifically aimed at younger audiences on platforms such as YouTube and Instagram. The show often ridiculed political correctness, and covered pop culture matters, soft news, and “vox-pops with members of the public […] seemingly attempting to stoke a sense of apathy with claims about how awful everyone is, and a sense of foreboding, if hilarious, doom surrounding the ills of modern (Western) society”.20 Additionally, RT UK became home for one of the longest-serving journalists for the network, Martyn Andrews. Prior to moving to the network’s UK branch, Andrews reported for RT from Moscow. As an openly gay journalist, and throughout his RT career (including his reporting from the Sochi 2014 Olympics), he has embodied “a more than symbolic rebuttal of the mainstream western media account” of Russia’s growing espousal of conservative values and homophobic political discourse.21 As a popular culture-focused reporter, Andrews continued to enact and provide – throughout his RT UK news reports and online op-eds – an alternative take on the views held by mainstream British media outlets on a variety of cultural, sport, political, and general interest stories; this alternative view was often aligned with official Russian political discourse.22 Finally, RT UK also benefited from RT International’s ability to capture the services of high-profile football personalities such as José Mourinho, Peter Schmeichel, and Stan Collymore for the network’s coverage of the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia. RT’s contribution to this Russian public diplomacy campaign has been received uncharacteristically positively by British audiences.23 Given such football stars’ notoriety in the UK, such programming undoubtedly helped RT attract new followers in that country.

In summation, through its staffing selections and programming trajectories, RT UK attempted to reach British audiences across both traditional and new media formats. It employed a variety of approaches to news discussions and interpretations across platforms. These ranged from the serious and often polemical tone of Going Underground, Alex Salmond Show, and Sputnik, to the more humorous entertainment- and culture-focused News Thing as well as Andrews and Boiko’s reporting. RT UK’s reporting style was characterised, among other things, by a focus on media-centricity and counter-hegemonic rhetoric.

Tensions between RT UK and the British political and media regulation establishment

RT UK’s strategy did not form and evolve within a vacuum. On one hand, it is linked to the overarching editorial practices and policies used by the wider RT network. On the other hand, RT UK’s content and approach to its programming has inevitably been shaped in response to the specific political environment in the UK, and the need to adhere to the local broadcasting code. The latter has been particularly significant in informing the fate of RT UK over the past few years. The Ofcom investigations, and the broadcaster’s legal battle with the regulator, are an important part of RT UK’s story.

In its nascent years, RT UK was the subject of minor Ofcom sanctions,24 but this scrutiny intensified following the 2018 Skripal affair.25 The regulator launched a detailed investigation of RT’s programmes that were broadcast in the UK during the months of March and April 2018, and subsequently found that in seven of these “RT failed to preserve due impartiality”.26 This key standard of British news reporting prompts news outlets to “include a sufficiently diverse range of opinions on matters of significant controversy”.27 One of the programmes found to be in breach of these standards was produced specifically by RT UK – George Galloway’s Sputnik – while the rest was programming by other RT branches that were shown in the UK. RT launched a formal judicial review of Ofcom’s investigation and rulings, but in 2020, the judiciary sided with the British regulator. Ofcom fined RT UK £200,000 for the breaches, and ordered the channel to convey to its audience a summary of Ofcom’s findings.28

The Ofcom sanctions stopped short of a formal “cease operations” order. The final ruling on Ofcom’s RT UK penalties in early 2020 shortly preceded a further political exposé of Russian activities in the UK, known as the “Russia Report”. This document summarised the examination, by the British Parliament’s intelligence and security committee, of interference in UK politics by Russian state-sponsored actors. The report argued that the British authorities had failed to seriously consider evidence suggesting that programming by RT and the radio network “Sputnik” featured a “preponderance of pro-Brexit or anti-EU stories”.29 The report further proposed that, coupled together with the social media activity of Russia-linked bots and trolls, RT UK had been part of a wider Russian campaign that aimed at influencing the Brexit vote and other democratic processes in the UK – the report stated that the British authorities did not adequately assess the influence of these actors.30

Like its parent international network, RT UK internalised and appropriated such assessments, serving as a “Kremlin propaganda bullhorn” in its self-positioning within the landscape of British broadcasting, and in its branding efforts to reach wider audiences. Nowhere else has this been clearer than during its infamous ad campaigns on the London tube and bus network. The campaign, aiming to drive the British audiences to RT UK’s content in a provocative fashion, featured messages that spanned London underground stops such as “[w]atch RT and find out who we are planning to hack next”.31 This was a clever attempt to use the network’s controversial status to attract viewers and online audiences disillusioned with British mainstream broadcasters and news sources.32 The criticism and outrage resulting from the campaign33 played right into the hands of RT’s messaging strategy; the latter aligns with what has been described as a “strategic humour” approach in Russia’s engagement with international audiences.34 By appropriating the crude labelling given by its adversaries, and relying on satire, humour, and “trolling” across its outputs and self-positioning,35 various branches of RT (including RT UK) attempt to present a self-confident image in “a vicious battle with the Western media establishment”.36

Any success of such audacious challenges to the order of and efforts to enter the British mediascape must be judged according to the level of resonance the content produced amongst British audiences. Herein lies one of the key arguments in the prominent debates around the need to resist and counteract RT UK, and other prominent Russian informational media actors, to protect British democracy and social cohesion. While the activities of such actors should, of course, not be dismissed, RT UK’s audience reach (and their possible effects) may be grossly overvalued. Previous research on this indicates that even at the height of its notoriety, RT UK only reached levels of around 0.01 percent of British TV viewers, despite being easily available.37 Social media platforms helped RT UK reach more people, but the number of followers remained far behind that of other RT network-owned branches, not to mention the followers of other high-profile international broadcasters in the UK and abroad.

For those members of the public whom RT does reach, recent audience surveys found that such content consumption takes place in the context of the viewers’ “awareness of RT’s national affiliation [and] desire to balance out perceived biases of mainstream sources”.38 The high viewing figures of a few of the viral clips shared by RT UK do not necessarily translate into dedicated following of RT’s outputs. In sum, while the presence of RT within the British media environment may have generated significant publicity, and the network did entice a small segment of the media audience in the country, its actual impact seems to have come up short of the initial objective. The following case study, of the mediation of a major political event, may help to illustrate this.

RT UK’s coverage of the 2019 General Election

RT UK’s reporting of a high-profile British political media event – which coincided with some scandals around the network – sheds light on how this broadcaster operates and to what degree its work is resonant with its audience. The British General Election took place on 12 December 2019 and saw the Conservative Party (the Tories) – led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson – heavily defeat the Labour Party and its leader Jeremy Corbyn, thereby gaining a commanding majority in Parliament. Relying on the live media ethnography method,39 I collected a set of outputs produced by RT UK on 6 December 2019.40 The date was chosen as the final Friday of the campaign period, a point at which all the key narratives of the election period reached a crescendo.41 The broadcast materials were recorded or accessed via the RT website, then transcribed, and analysed using content and qualitative methods.42 Additionally, data from RT UK’s website and a variety of relevant social media channels – introduced in more detail below – was collected and coded by the author.

The goal was to identify and understand RT’s key messages, and the modes of informing and connecting to the audience that were exhibited in RT’s coverage of these elections. I also attempted to assess whether RT UK uniformly and noticeably spurred its viewers to favour some candidates whilst discrediting others across its media channels and different outputs. Finally, I tried to trace what kind of technologies, formats, and themes were used in the election coverage, and how effective and impactful were RT’s approaches to mediation of the election.

On the whole, all the key topics prevalent in the coverage of this election in other British outlets – including Brexit, business, economy and trade, healthcare, media standards and scandals, and taxation43 – were also evident in RT UK’s coverage. Apart from the network’s closer attention to the business of media scandals, the Russian broadcaster’s agenda-setting mediation contribution to the British election campaign was not markedly distinct from that of the other news outlets. However, upon closer examination, there are traces of overarching messages and political preferences that are exhibited right across RT UK’s reporting of this general election. These are summarised below.

RT UK News Bulletin

I first examined the RT UK News Bulletin that was broadcast at 7pm on 6 December 2019.44 On the surface, the bulletin tried to balance its coverage of the election by reporting the daily news as well as on activities related to all major parties in the election. However, the framing and salience of reporting was notably skewed. The Conservative Party and its leader were the focus of a single report in the elections section of the newscast. In this report, the reporter poked fun at the “Get Britain out of Neutral” slogan adopted by the Tory campaign. Instead of providing an expert guest view on the Tories’ activities that day, RT UK featured humorous tweets about the slogan and the visual mistake made in the unveiling of this campaign. This instance exemplified the noted counter-hegemonic practices regularly employed by RT personnel, who often use humour, satire, and mockery to undermine Western institutions and their representatives whom they wish to discredit.45

Johnson and the Conservatives’ campaign did appear and were given voice in the other bulletin segments that focused on the Labour campaign. Such appearances tended to be given a negative slant. Reporting on other key election topics was similarly presented, through a lens antagonistic to the current Conservative government; for example, a lengthy report and in-studio interview with a “Brexit expert” explained how the government-proposed plan to leave the EU was misleading.

In a sharp juxtaposition, the Labour activities for that day – for example, Corbyn’s press conference – were presented in a more serious and considerate tone. The press conference, held on the morning of 6 December, was widely covered across various RT UK platforms, including the RT UK News Bulletin. Corbyn’s public statement evaluated the nature of a US-UK trade deal document, which subsequently was alleged to have been leaked to Labour from a Russian source.46 The controversy around this document, in general, “fuelled a debate about the future of the NHS and made the headlines for days, particularly after evidence emerged blaming Russians for the leak”.47 The reporting by RT UK about that day’s conference did not touch upon the source of the document Corbyn was discussing. Instead, during an in-studio interview with an RT UK reporter, the host unpicked the points made in Corbyn’s accusations of the government’s Brexit plans. This obviously contrasted with the whimsical tone of the broadcaster’s report on Johnson and the Conservatives’ campaign that was shown prior to this in-studio discussion.

The exchange between the reporter and the news bulletin host legitimised the accusations made by Corbyn, and implied the Prime Minister was lying about his Brexit plan; at the same time, the potential hardships to the British people as a result of this issue was also highlighted. The in-studio exchange suggested that, as a result of the leaked information, Corbyn would have the upper hand during the televised debate between the party leaders that was scheduled later that evening. The notably anti-Brexit, pro-Labour stance of the bulletin supports the findings of previous research: that RT’s editorial policy is mercurial in terms of its political orientation as long as the views expressed challenge Western democratic institutions.48 For example, some reporting across RT’s networks was sympathetic towards Brexit in previous years,49 but RT UK’s election coverage took the opposite stand. Likewise, other branches of RT obviously supported right-leaning rather than left-leaning parties and candidates in previous major election campaigns, such as in the case of RT’s coverage of the 2020 US presidential elections.50

The bulletin covered activities of other political parties participating in the election, but the coverage consisted of mere seconds-long highlights of the respective campaigns. The Scottish National Party, the Brexit Party, the Green Party, and the nationalist Welsh party Plaid Cymru were in primary focus for a total 2.2 percent of the newscast’s length. The rest of the news bulletin’s coverage reflected negatively on the current UK government. Any links to the election were implicit yet evident: stories critiqued Johnson’s and previous Conservative governments but passed no judgement on whether a Labour cabinet would have done a better job. The additional storylines in the bulletin explained that: the threat of Russian disinformation was inflated by the British government and its military command; the current government’s own diplomat was quitting her job because of the Brexit “mess”; the government and local authorities’ handling of the Grenfell Tower incident was “shameful”. Altogether, despite a clear preference for one party over another in the election campaign, the newscast’s messaging was more interested in challenging the current UK government, rather than narrowly serving as a Labour campaign communications tool.

Special programming

Interestingly, RT UK’s two high-profile political discussion programmes introduced above – the Alex Salmond Show and George Galloway’s Sputnik – did not dedicate any attention to the upcoming elections in the episodes aired on collection dates.51 Instead, the former provided a discussion of the issue of Catalan independence, while the latter debated standards of good journalism. Despite the proximity of the election, RT UK’s programming was not completely overtaken by this important political event, and the network continued to engage its viewers by using a variety of subject matter.

The third major political discussion show of RT UK, Afshin Rattansi’s Going Underground (broadcast on 7 December 2019), provided a detailed discussion of the upcoming election – during the host’s interview with the newly-appointed Russian ambassador to the UK. This programme served as a more traditional exercise of public diplomacy by a Russian informational actor. Its goal was to introduce RT UK viewers to the new Russian ambassador, Andrei Kelin, and discuss Russia’s official position on a range of issues concerning the British public. The programme broadly signified RT UK’s own internalised stance on the election and the network’s role within the British media sphere: (a) that its influence was grossly exaggerated (articulated in the ambassador’s dismissive responses to Rattansi’s questions about Russian interference in British domestic affairs); (b) that RT UK presented a balanced and unbiased take on the election and on other British political affairs (through the host’s frank questioning on key controversial issues); and (c) that it provided an alternative voice, on behalf of Russia and its government, compared to other mainstream outlets in the UK (in this case, through the direct public diplomacy appeal of the interview and its subject’s dismissal of popular anti-Kremlin narratives circulating in mainstream British media). The latter point was highlighted by the fact that Rattansi did not push for answers on sensitive questions (brought up similarly by other mainstream outlets) when the Russian ambassador asked him not to. A different interviewer may have prompted the more combative and “truth-seeking” approach sometimes utilised in RT programming, whereas here, the controversial subjects were brought up but not fully explored.

Election coverage on the RT UK website and on social media platforms

Election coverage on the RT website – on and around 6 December 2019 – was more multi-directional when compared with the RT UK News Bulletin and the special programming. There were stories that presented the leader of the Tories in a negative light. One of the headings, for example, was “Pedalling porkies? BoJo claims CYCLING on the pavement is the ‘NAUGHTIEST’’ thing he’s ever done”, which highlighted RT’s tactic of “tabloidisation” and a “click-bait” style of presenting online content.52 There were other stories as well, which were framed in a manner sympathetic with Johnson’s rhetoric and that questioned the Labour campaign. This was not noticeable in the broadcast content.53 Significantly, the news reporting on the website demonstrated a keen interest in the media coverage and in social media reactions to the election campaign: “‘Where’s the grilling you gave Jeremy Corbyn?’ TV breakfast show hosts slammed online for giving BoJo easy ride with ‘cosy chat’”54 and “‘Fairly hefty clanger’: Channel 4 misquotes BoJo as saying he wanted control over migration of ‘people of colour’”.55 The theme of accusing various media outlets of their biased or inaccurate coverage of the election exemplifies RT UK’s media-centric approach to news coverage.

RT UK covered the issue of (perceived) unfair and biased mediation of the campaign across its news outputs and platforms, featuring examples from both anti-Tory and anti-Labour mainstream British media coverage. Such stories might have had more resonance with RT UK’s Labour-leaning audience; as another study argued, Labour supporters were the ones for whom the issue of biased and inadequate mediation of the election was particularly appealing.56 Overall, however, the Conservatives and news related to their 2019 campaign received more attention on RT’s news website when compared with the broadcast news bulletins investigated here. This suggests that the approach to the selection and coverage of subject matter is not in seamless sync across RT UK’s broadcast and web production teams at all times.

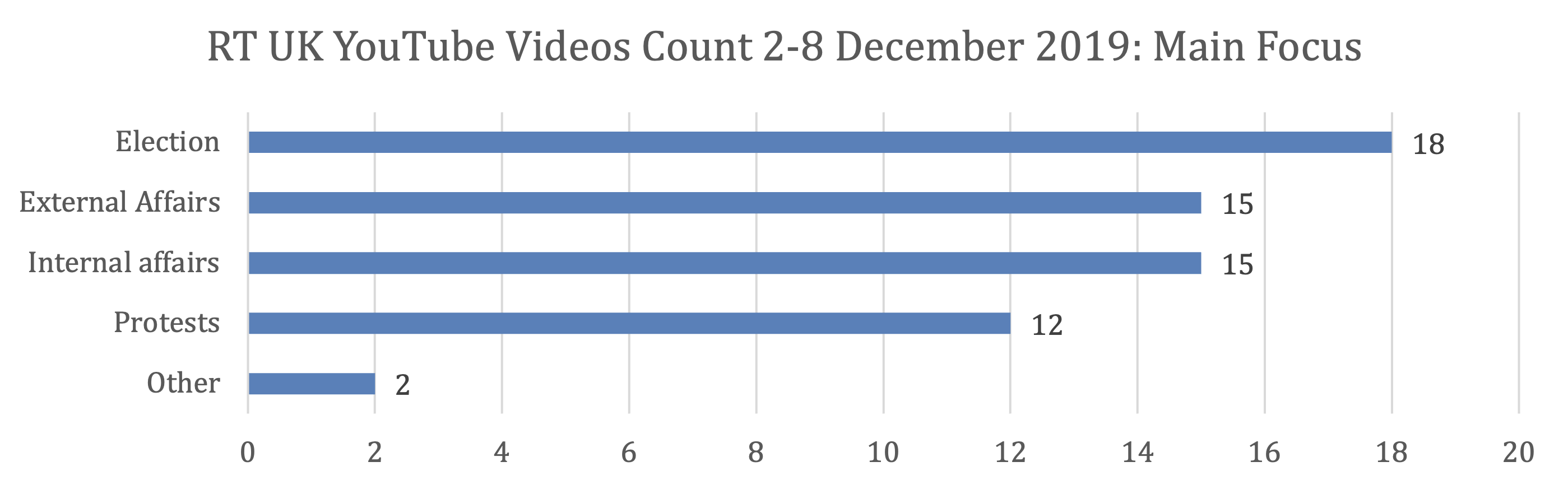

The social media output of RT UK programmes and its employees deserves a more detailed look than may be feasible to fully discuss within this short chapter, but some of the highlights presented below point to important trends: on YouTube, for the week 2-8 December 2019, RT UK’s service shared 62 videos on its channel. The election was the most prominent subject in these videos, with 18 videos in total addressing election-related news and issues. When compared with other RT UK platforms, election-related content on YouTube was not as salient: less than a third (29 percent) of content on this channel directly addressed the election. Compare this with the RT UK broadcast news bulletins studied here, and the RT UK Twitter account, where 41.9 percent of total coverage and 45 percent of the daily coverage on 6 December were (respectively) dedicated directly to the election.

The approach used by RT UK to share election-related and other content on its YouTube channel seemed to have a multi-prong strategy of targeting and engaging a variety of viewers. The live stream of Jeremy Corbyn’s press conference, for example, was one of the most prominent videos posted by RT UK during the investigated week. The same press conference was live-streamed on YouTube by two leading British newspapers, The Guardian and The Telegraph. The Guardian’s stream57 was viewed nearly ten times more than that shared by RT UK (12,100 compared with 1,486 views at the time of analysis), and The Telegraph’s coverage58 attracted about 20 times more views than that of RT UK (30,200 compared with 1,486 views). Despite reaching far fewer online users, RT UK’s version of the live-stream was in fact comparatively very successful in generating online discussions amongst its YouTube viewers. RT UK’s version resulted in 177 public comments, more than The Guardian’s version (167 comments) but fewer than The Telegraph’s (272). This may serve as evidence of RT UK’s content followers being more proactive YouTube users, who are ready to engage in discussions on election-related media content.

No-commentary footage clips were another popular and frequently used type of YouTube videos shared by RT UK. One such clip shared excerpts from Nicola Sturgeon’s campaign appearance, in which she urged Scottish voters to prevent a Conservative majority and the inevitability of Brexit it would bring about. Although much shorter than the live stream of Corbyn’s press conference, the footage of Sturgeon’s appearance and her anti-Brexit claims showcased the general anti-Tory stance of RT UK’s outputs in connection to the election. The video resulted in the highest number of user comments, and showcased a broad division amongst participants on the issues of Brexit, Scottish independence, and party preferences. This example serves as further evidence of RT’s interest and success in causing emotional responses from its online and offline audiences; these audiences were reached by a variety of output formats and platforms through which such content was shared.

The official RT UK news service account on Twitter (@RTUKnews), which had 95,000 followers at the time of writing, shared 22 tweets on 6 December 2019. Only ten of these were directly related to the election (45 percent of the daily coverage). Seven tweets (32 percent of the daily coverage) expressed sentiments, or circulated news stories, that were antagonistic to the Tory campaign or to the current government. Two messages shared positive or supportive updates on the Labour campaign, the same number as positive or favourable tweets about the Tory campaign. Two tweets (nine percent) provided updates on the campaigns of other political parties: the SNP and the Brexit Party. Brexit featured comparatively prominently: four tweets (18 percent) both in the context of the election and from the standpoint of broader economic impact. Mediation of the election by various British media outlets also formed a distinct avenue of RT UK’s Twitter activity: three tweets (14 percent of all daily posts). Overall, while negative undertones in the coverage of the Conservative campaign and the current UK government’s activities were prominent in @RTUKnews’ messages, the election, scheduled to take place in just a few days, made up less than half of all Twitter activity on this channel on 6 December 2019. Stories about crime and justice, sports, international business, and viral Internet content (such as cat videos, and other unrelated topics) jointly made up a larger portion of the daily Twitter coverage than general elections-related news.

The personal account of Afshin Rattansi (@afshinrattansi, 14,400 followers at the time of writing), the host of Going Underground, provided a different case study of the election’s online coverage by RT and its journalists on Twitter. Rattansi was, on average, more active than the RT UK news service account. Between 9 and 11 December, when the data was available, he shared at least 124 tweets: approximately 41 tweets per day. Notably, almost two thirds of all his messages directly addressed election-related issues (77 tweets, 62 percent of the sample). Unlike the @RTUKnews feed, the issues of Brexit, other parties’ participation in the election, as well as any positive sentiment towards the Tory campaign, were virtually absent from the sample. Rattansi’s personal political preferences became clear from the analysis of the collected messages: a third of his tweets (40, or 32 percent of the sample) were sympathetic towards, or directly endorsed, the Labour campaign and/or Jeremy Corbyn. A negative light on the Tory campaign or Boris Johnson’s leadership was shed in 37 messages (nearly 30 percent of the sample). More significantly, however, was Rattansi’s clear intention to expose and showcase the political bias demonstrated by a range of British media outlets during their coverage of the election. More than half of his tweets (63 messages, 51 percent of the sample) directly addressed the issue of unfair mediation of the election. He specifically attacked the BBC, on a range of its programmes and journalists, for their alleged bias and preferential reporting of the Tories, and their unfair reporting of the Labour campaign.

In comparison, the account of the show Rattansi hosted (@Underground_RT, 26,211 followers at the time of writing), dedicated much less attention to the issues related to the election. Between 2 and 11 December 2019, @Underground_RT shared 83 tweets. Among them, just over ten percent (nine tweets out of 83) directly addressed the issue of the upcoming election. Similar to the account of the show’s host, these tweets criticised the Tory campaign, supported the Labour campaign, and questioned the balance of other media outlets’ coverage of the election. RT UK journalists’ accounts, therefore, do not appear to be regulated as strictly when compared with the protocols guiding BBC journalists’ online presence. The RT UK’s staff personal social media activity may be on par with, or even more resonant than, the social media pages of the programmes they host. This emphasises just how important it is for channels such as RT UK to make the right staffing choices.

While there were some differences in the overall approach to delivery, and in the editorial selection of the stories disseminated, through various RT UK platforms, the overarching (and self-evident) message projected in its election coverage aimed at undermining the current government and the Tory campaign; the election itself, though, was far from being the exclusive focus for RT’s content managers. The reach of the channels was modest at best, and even then, as suggested in other research, members of RT’s audiences in the UK consumed the network’s broadcast news and new media content as part of “a varied media diet, which includes mainstream international sources”.59

RT UK’s audience reach during the 2019 General Election

To be comprehensive, any discussion about the outputs of an information network needs a twin consideration of their reach and possible impact amongst its audiences. The Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board (BARB), an audience research agency, suggested that the RT UK TV broadcast audience reached 0.51 percent of all audiences, or 310,000 viewers, in the week commencing 2 to 8 December 2019. An average daily TV viewer audience in the UK was 68,000, while the time spent watching RT’s TV content was negligible, amounting to 0.01 percent of average weekly share of viewing (less than a second, per average viewer).60 The viewing figures for the Facebook live-stream of the Labour press conference on 6 December (discussed above) nearly equalled RT’s average daily TV audience, highlighting the significance of new media platforms in RT UK’s ability to reach viewers in the UK. The BARB report on live-streaming of RT’s content in the UK, via RT’s own app or Sky GO service, reflects how marginal the share of dissemination was of the Russian state-backed channel via online broadcast delivery, when compared with other major broadcasters. The report suggested RT’s content was streamed for a total of 7,363 minutes during that same week, whereas Fox News’ content was streamed for 3.6 million minutes, and BBC for 132.9 million minutes.61

Another report provided a specific reflection on the Russia-backed outlets’ share of online news consumption during the entire election campaign: “[F]oreign sites like Russia Today and Sputnik played a relatively small part with just 1 percent share of the time spent with news, about 0.02 percent of the time people spent online during the election”.62 Such figures provide a sense of the modest audience reach of RT UK’s outputs. The new media channels also have reached a significantly smaller number of online users when compared with the accounts of other major UK media outlets. None of the online content reached viral status – something that happens on occasion with RT’s online satirical posts, licensed video shorts, or videos of disasters63 – but this was not observed for the period of investigation.

Another report provided a specific reflection on the Russia-backed outlets’ share of online news consumption during the entire election campaign: “[F]oreign sites like Russia Today and Sputnik played a relatively small part with just 1 percent share of the time spent with news, about 0.02 percent of the time people spent online during the election”.62 Such figures provide a sense of the modest audience reach of RT UK’s outputs. The new media channels also have reached a significantly smaller number of online users when compared with the accounts of other major UK media outlets. None of the online content reached viral status – something that happens on occasion with RT’s online satirical posts, licensed video shorts, or videos of disasters63 – but this was not observed for the period of investigation.

To assess the role of RT UK in influencing UK domestic affairs, it would help to have: (1) a better understanding of the makeup of RT’s audiences, and (2) wider patterns of voter preferences and attitudes towards political news consumption during election periods in the UK. Some of the audience reactions and engagement patterns observed in my analysis suggests that voters across the political spectrum followed and engaged with RT UK’s content, and with one another, on the network’s online platforms. Fletcher and colleagues argue that the major problem around mediation of the 2019 election was not that media organisations drove polarisation of public opinion on key issues such as Brexit but “that many people do not engage much with news at all, spending just 3 percent of their time online”.64 RT UK’s coverage presented an alternative option for UK voters to obtain and discuss election-related news, even if its reach was comparatively small.

More credit needs to be given to the audiences of political news content in being able to engage with and make judgements based on reported news. As suggested in a study on the patterns of news consumption during the British 2019 elections, “most news users accessed a variety of sources, including both sources aligned with their own political views and sources that challenge them”,65 thus breaking through the mooted echo chambers of election-related information. The same should be true of RT UK’s audiences. The network’s influence on British voter preferences should not be overestimated, yet its role should not be disregarded entirely. It has reached a segment of UK voters and provided them with a particular framing of election-related news. RT UK also supplied multiple platforms for its viewers and audiences to interact with one another ahead of the December 2019 election.

Conclusions

While RT UK has not officially endorsed any of the participating parties in this election, the cross-platform outputs on and around 6 December 2019 suggest the overarching leaning of the network and its employees in supporting the Labour campaign, though the salience of this leaning did vary across platforms. In contrast, the Conservatives’ campaign was lacking the same rigour of coverage, and Boris Johnson was often mocked. Brexit, one of the key issues surrounding the election, was persistently portrayed in negative tones. It would be inaccurate to state that RT UK’s coverage was entirely entrenched in its pro-Labour, anti-Tory configuration. There are stories that “side with” the Conservative campaign, but these were noted when RT UK attacked the biased coverage of the mainstream media, helping the channel to challenge the status quo of the British news media landscape. There were cases of simple, factual reporting on the Tories’ activities, and those that provided a seemingly balanced overview of the two parties’ positions on key election issues, thereby prompting audiences to decide for themselves. RT UK’s news coverage of the election did feature overviews of activities of other participating political parties, most notably, SNP and the Brexit Party, across various platforms, but these were comparatively marginal. The total coverage of the Green Party’s activity across all investigated RT UK platforms consisted of a five seconds-long mention in the evening news bulletin.

Such a slant in RT UK’s reporting contrasted sharply with RT’s approach to coverage of the 2020 US presidential elections, in which the network’s reporting leaned strongly towards endorsing the right-wing Republicans. Moreover, whereas the standards of RT America’s coverage of the election across the Atlantic was found to be seriously flawed on multiple occasions,66 my analysis of RT UK’s coverage of the UK elections did not uncover obvious signs of unacceptably low standards of journalistic practice. This supports the experts’ previous conclusions that, “content produced for RT UK (under Ofcom’s remit) is markedly more balanced than content produced for RT America”.67 The ability of the British media regulatory system to keep the activity of such foreign informational actors as RT UK in check, is therefore key in endorsing adequate standards of news reporting during such important periods of democratic processes such as election campaigns.

A major distinctive feature of RT UK’s reporting of the UK 2019 election was the salience of stories that questioned and undermined the coverage of the campaign by other mainstream media outlets. Such a strategy fit well with RT’s overarching counter-hegemonic ethos, both with respect to its own self-position in the global media sphere68 and in its appeal to audiences interested in assaults on established media institutions.69 This may explain RT’s apparent interest in exposing the biased and questionable expertise of rival outlets, even when it advances the position of the Conservative party and its leader (such as in the case of the Channel 4 misquotation of a Boris Johnson speech). In this case, the apparent need to emphasise the supposed misstep by a rival media organisation trumped an opportunity to engage with the subject matter of Johnson’s speech in question, thereby highlighting RT’s interest in reporting controversial and potentially viral content.

A report exploring the mediation of the election in the same period by major British outlets found that the “final week of the campaign saw the highest levels of newspaper negativity towards the Labour party. Negativity also increased towards other opposition parties, whereas the Conservatives’ position improved on that of the penultimate week”.70 This could be explained by the fact that Labour-endorsing mainstream media outlets were significantly fewer in number compared with the outlets openly endorsing the Conservative Party during this election.71 This election-reporting landscape could have facilitated RT UK’s situational alignment, and the network’s staff’s personal biases, in this instance. This may be a consequence of Moscow’s delegation of journalistic and editorial agency to subordinate actors, especially when foreign staff are not fully acculturated to Kremlin positions. RT UK’s overarching sympathetic view of Labour activities in the studied period may be explained not only by the personal political preferences of reporters captured in this study, but also the network’s counter-hegemonic positioning vis-à-vis mainstream British news sources, and a desire to present the British government in a negative light.

Overall, there are signs of RT UK’s obvious continuity with the mode of operations of its parent network; this is apparent in its activities across its news production and dissemination, the style and content of reports, staff hiring practices, and other features. Yet, given the close oversight of its activities by British media regulators, RT UK does constitute a unique case within RT’s international network, and prompted the need for a more careful approach to news dissemination and discussion. In this context, RT UK’s coverage of the 2019 elections presents an excellent case study of the network’s efforts to at once integrate in, and shake up, the existing media environment within which it operated. This instance showcases the channel’s initial ambition in its multi-pronged and cross-media approach to informing British audiences of significant political developments both in the UK and internationally. The “media-centricity” of RT UK’s coverage of the election, or the persisting interest in pinpointing how mainstream outlets misreport on issues of significance,72 illustrates how the network challenges the alignment of the British media sphere.

The prominence of the debates around RT UK’s activities as a threat to British democracy73 is a sign that this element of RT UK’s ambition is successful, at least to a degree. At the same time, its 2019 election reporting presents clear evidence that the perceived damage the channel could cause to the British democratic practices may have been overblown. Being burned by Ofcom’s close monitoring and sanctioned for previous missteps, RT UK’s coverage of the election was often factual, situationally supporting the Labour campaign and being biased against the current British government. Tiny TV audiences reached modest success in terms of the deployment of new media platforms, and showcased that RT UK, as of the end of the 2010s, was far from reaching the initial goals that were self-proclaimed by the network upon its launch. It suffered a further setback in the form of the recent discontinuation of the broadcast news production.

Endnotes

1. This work was additionally supported by the AHRC under Grant No. AH/P00508X/1. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) in the production of this report is also gratefully acknowledged.

2. “RT Launches Dedicated UK News Channel – RT UK”, RT, 29 October 2014, https://www.rt.com/uk/200411-rt-uk-channel-launch/.

3. Ibid.

4. Patrick Wintour, Jim Waterson, “Jeremy Hunt: Russian TV Station a ‘Weapon of Disinformation’”, The Guardian, 1 May 2019, http://www.theguardian.com/media/2019/may/01/jeremy-hunt-russian-tv-station-a-weapon-of-disinformation.

5. “RT Launches Dedicated UK News Channel”.

6. Ibid.

7. “RT UK”, YouTube, https://web.archive.org/web/20220124012244/https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC_ab7FFA2ACk2yTHgNan8lQ.

8. “The Alex Salmond Show”, RT, https://www.rt.com/shows/alex-salmond-show/.

9. Graham Ruddick, “‘Be Ashamed, Alex’: Salmond Courts Controversy with RT”, The Guardian, 17 November (2017), http://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/nov/17/be-ashamed-alex-salmond-courts-controversy-rt-russia-today.

10. Paris Gourtsoyannis, “Alex Salmond Comes under Renewed Pressure to Abandon Russian Channel RT”, The Scotsman, 23 July (2020), https://www.scotsman.com/news/politics/alex-salmond-comes-under-renewed-pressure-abandon-russian-channel-rt-2921504.

11. Nigel Morris, “George Galloway’s Result at the Batley and Spen By-Election Proves He Can Never Be Written off”, INews, 2 July (2021), https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/george-galloway-batley-and-spen-by-election-results-votes-candidates-1083223.

12. “Sputnik Orbiting the World”, RT, https://www.rt.com/shows/sputnik/.

13. Stephen Hutchings, “RT and the Digital Revolution: Reframing Russia for a Mediatized World”, in Andy Byford, Connor Doak, Stephen Hutchings (eds), Transnational Russian Studies (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2019), pp. 283-300 (287).

14. See, for example, the debates around Galloway and Salmond’s RT contracts in Scottish media: David Leask, “Strange Case of George Galloway, Unionism and Putin’s RT Mouthpiece”, The Herald, 12 March (2021), https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/19154093.strange-case-george-galloway-unionism-putins-rt-mouthpiece/.

15. “On-Air Talent: Afshin Rattansi”, RT, https://web.archive.org/web/20220301195333/https://www.rt.com/onair-talent/afshin-rattansi/.

16. “Going Underground”, RT, https://www.rt.com/shows/going-underground/.

17. Vera Tolz, Stephen Hutchings, Precious N. Chatterjee-Doody, Rhys Crilley, “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency: Russian Television Coverage of the Skripal Poisonings”, Journalism, Vol. 22, No. 12 (2021), pp. 2971-2990.

18. Lucy Birge, Precious N. Chatterje-Doody, “Russian Public Diplomacy: Questioning Certainties in Uncertain Times”, in Pawel Surowiec, Ilan Manor (eds), Public Diplomacy and the Politics of Uncertainty (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021), pp. 171-195 (181).

19. “News Thing”, RT, https://www.rt.com/shows/news-thing/.

20. Rhys Crilley, Precious N. Chatterje-Doody, “From Russia with Lols: Humour, RT, and the Legitimation of Russian Foreign Policy”, Global Society, Vol. 35, No. 2 (2021), pp. 269-288 (280).

21. Stephen Hutchings, Marie Gillespie, Ilya Yablokov, Ilia Lvov, Alexander Voss, “Staging the Sochi Winter Olympics 2014 on Russia Today and BBC World News: From Soft Power to Geopolitical Crisis”, Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2015), pp. 630-658 (642).

22. E.g. Martyn Andrews, “Recipe for Disaster: BBC Adds Politics & History to Borscht and Serves It up to Add More Bitterness to Russia-Ukraine Relations”, RT, 17 October (2019), https://www.rt.com/op-ed/471139-borscht-bbc-russia-ukraine/; Martyn Andrews, “Snowflake Culture Soars as Children Could Be Banned from Heading Balls in Scotland”, RT, 18 January (2020), https://www.rt.com/op-ed/478436-children-ball-ban-scotland/.

23. Rhys Crilley, Marie Gillespie, Vitaly Kazakov, Alistair Willis, “‘Russia Isn’t a Country of Putins!’: How RT Bridged the Credibility Gap in Russian Public Diplomacy during the 2018 FIFA World Cup”, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Vol. 24, No. 1 (2022), pp. 136-152.

24. Jasper Jackson, “RT Sanctioned by Ofcom over Series of Misleading and Biased Articles”, The Guardian, 21 September (2015), http://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/sep/21/rt-sanctioned-over-series-of-misleading-articles-by-media-watchdog.

25. For more details see Stephen Hutchings, Vera Tolz, Precious N. Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge: How to Respond to Russia’s International Broadcaster”, Policy@Manchester, July (2019), https://reframingrussia.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/reframing-russia-policy-brief-july-2019-.pdf; Stephen Hutchings, Rhys Crilley, Precious Chatterje-Doody, “Ofcom’s Latest Ruling on RT Is More Significant than You Might Think”, HuffPost UK, 21 December (2018), https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/ofcom-rt-bbc-latest_uk_5c1ce1b8e4b08aaf7a87c17c.

26. “Ofcom Fines RT £200,000”, Ofcom, 26 July (2019), https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom/latest/media/media-releases/2019/ofcom-fines-rt.

27. Hutchings, Tolz, Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge”.

28. “Russian Claim against Ofcom Dismissed”, BBC News, 27 March (2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-52066359.

29. Dan Sabbagh, Luke Harding, Andrew Roth, “Russia Report Reveals UK Government Failed to Investigate Kremlin Interference”, The Guardian, 21 July (2020), http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/21/russia-report-reveals-uk-government-failed-to-address-kremlin-interference-scottish-referendum-brexit.

30. Ibid.

31. The campaign also ran in New York and at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport.

32. Hutchings, “RT and the Digital Revolution”.

33. Jessica Elgot, “RT Spent £310,000 on London Transport Ads, TfL Figures Suggest”, The Guardian, 14 December (2017), http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/dec/14/rt-london-transport-ads-tfl-transport-for-london.

34. Dmitry Chernobrov, “Strategic Humour: Public Diplomacy and Comic Framing of Foreign Policy Issues”, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2022), pp. 277-296.

35. Crilley, Chatterje-Doody, “From Russia with Lols”.

36. Stephen Hutchings, “Revolution from the Margins: Commemorating 1917 and RT’s Scandalising of the Established Order”, European Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 23, No. 3 (2020), pp. 315-334 (330).

37. Hutchings, Tolz, Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge”.

38. Ibid.

39. “Close, real-time, observation and logging of a wide range of media material across the network’s platforms and including responses to and contributions from social media users”; see Andrew Chadwick, The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 71.

40. Or the closest date immediately prior or after the day on which relevant RT UK programmes were available.

41. Daniel O’Donoghue, “Nine Key Moments from the 2019 General Election Campaign”, Press and Journal, 12 December (2019), https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/news/politics/uk-politics/1908847/nine-key-moments-from-the-2019-general-election-campaign/.

42. Nelson Phillips, Cynthia Hardy, Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction (London: Sage Publications, 2002).

43. David Deacon, Jackie Goode, David Smith, Dominic Wring, John Downey, Cristian Vaccari, “Report 5: 7 November – 11 December 2019”, Loughborough University, https://www.lboro.ac.uk/news-events/general-election/report-5/.

44. “RT UK News”, RT TV Channel, 6 December (2019).

45. Hutchings et al., “Staging the Sochi Winter Olympics 2014”; Chernobrov, “Strategic Humour”; Crilley, Chatterje-Doody, “From Russia with Lols”.

46. Patrick Wintour, “To Corbyn’s Dismay, the Story of the US-UK Dossier Has Mostly Been Its Origin”, The Guardian, 3 August (2020), http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/aug/03/to-corbyns-dismay-the-story-of-the-us-uk-dossier-has-mostly-been-its-origin.

47. Marco Silva, “General Election 2019: What’s the Evidence That Russia Interfered?”, BBC News, 11 March (2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-51776404; Ben Nimmo, “UK Trade Leaks: Operators Keen to Hide Their Identities Disseminated Leaked UK/US Trade Documents in a Similar Fashion to Russian Operation ‘Secondary Infektion’ Exposed in June 2019”, Graphika, 8 December (2019), https://web.archive.org/web/20200214143338/https://graphika.com/uploads/UK%20Trade%20Leaks%20-%20Updated%2012.12.pdf.

48. See the list of academic outputs of the “Reframing Russia” project for discussions on various manifestations of this feature in RT’s reporting: https://reframingrussia.com/academic-publications/.

49. Mona Elswah, Philip N. Howard, “‘Anything that Causes Chaos’: The Organisational Behaviour of Russia Today (RT)”, Journal of Communication, Vol. 70, No. 5 (2020), pp. 623-645; Emma Flaherty, Laura Roselle, “Contentious Narratives and Europe: Conspiracy Theories and Strategic Narratives Surrounding RT’s Brexit News Coverage”, Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 71, No. 1.5 (2018), pp. 53-60.

50. Vera Tolz, Vitaly Kazakov, “The US Presidential Election through a Russian Media Lens: From Domestic Legitimacy to Global (Mis)Information”, Reframing Russia for the Global Mediasphere, 24 November (2020), https://reframingrussia.com/2020/11/24/the-us-presidential-election-through-a-russian-media-lens-from-domestic-legitimacy-to-global-misinformation/.

51. As both programmes are not aired daily, the episodes examined were shown on 5 and 7 December 2019 respectively, the closest dates on which the programmes were available to the target collection date of 6 December 2019.

52. Galina Miazhevich, “Nation Branding in the Post-Broadcast Era: The Case of RT”, European Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, No. 5 (2018), pp. 575-593.

53. For example, “Boris Johnson Compares Leaked NHS Dossier to ‘UFO Photographs’”, RT, 5 December (2019), https://www.rt.com/uk/475127-boris-johnson-nhs-ufos/.

54. “‘Where’s the Grilling You Gave Jeremy Corbyn?’ TV Breakfast Show Hosts Slammed Online for Giving BoJo Easy Ride with ‘Cosy Chat’”, RT, 5 December (2019), https://www.rt.com/uk/475118-schofield-willoughby-boris-chat-slammed/.

55. “‘Fairly Hefty Clanger’: Channel 4 Misquotes BoJo as Saying He Wanted Control over Migration of ‘People of Colour’”, RT, 6 December (2019), https://www.rt.com/uk/475210-boris-johnson-people-of-talent/.

56. Richard Fletcher, Nic Newman, Anne Schulz, “A Mile Wide, an Inch Deep: Online News and Media Use in the 2019 UK General Election”, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 5 February (2020), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-02/Fletcher_News_Use_During_the_Election_FINAL.pdf.

57. “Jeremy Corbyn on the Election Campaign Trail – Watch Live”, YouTube, 6 December (2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6IjmUz1xD1c.

58. “Watch Again | Jeremy Corbyn: We’ve Caught Boris Johnson “Red-Handed”| General Election 2019”, YouTube, 6 December (2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9SIAzykduUA.

59. Hutchings, Tolz, Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge”.

60. See weekly TV set viewing summary for 2-8 December 2019 here: https://www.barb.co.uk/viewing-data/weekly-viewing-summary/.

61. See numbers for BBC, Fox Networks Group (UK) Ltd. and Russia Today TV UK Ltd for 2-8 December 2019 here: https://www.barb.co.uk/bvod-services/live-streaming-by-broadcaster-group-1-week-open/.

62. Fletcher, Newman, Schulz, “A Mile Wide, an Inch Deep”, pp. 2-3.

63. Hutchings, Tolz, Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge”.

64. Fletcher, Newman, Schulz, “A Mile Wide, an Inch Deep”, p. 4.

65. Ibid., p. 2.

66. See more in Tolz, Kazakov, “The US Presidential Election through a Russian Media Lens”.

67. Hutchings, Tolz, Chatterje-Doody, “The RT Challenge”.

68. Miazhevich, “Nation Branding in the Post-Broadcast Era”.

69. Hutchings et al., “Staging the Sochi Winter Olympics 2014”; Ilya Yablokov, “Conspiracy Theories as a Russian Public Diplomacy Tool: The Case of Russia Today (RT)”, Politics, Vol. 35, No. 3-4 (2015), pp. 301-315.

70. Deacon et al., “Report 5”.

71. Fletcher, Newman, Schulz, “A Mile Wide, an Inch Deep”.

72. Tolz et al., “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency”.

73. Sabbagh, Harding, Roth, “Russia Report Reveals UK Government Failed to Investigate Kremlin Interference”.