Sandarmokh, a Symbol of Russia’s Historical Responsibility for Colonial Violence against Ukraine

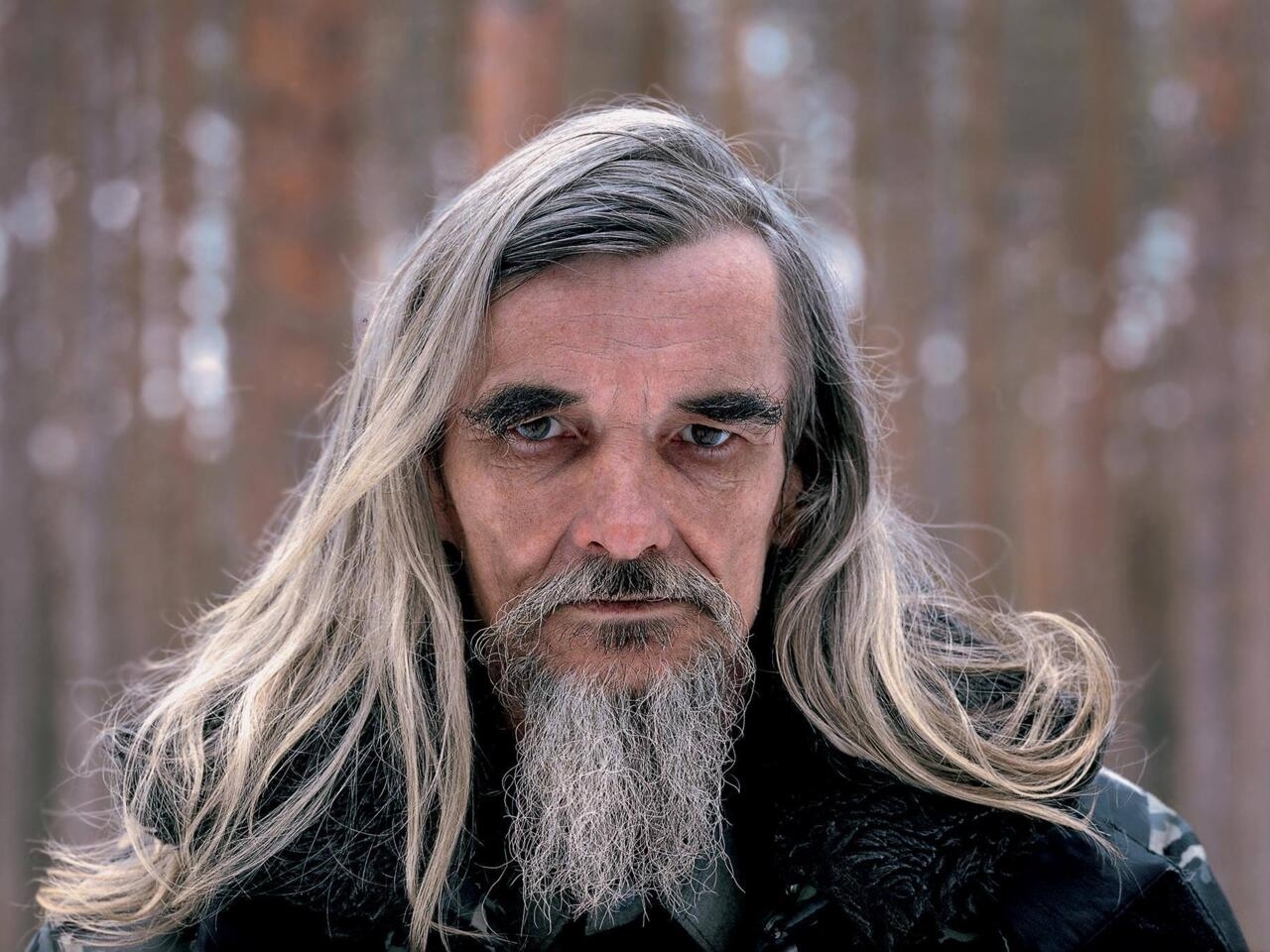

Sergei Lebedev

[This article is part of our research initiative “Russia’s Project ‘Anti-Ukraine’”]

From Sandarmokh to Bucha

After 24 February 2022, it is possible to speak about Russia’s future only in an inseparable connection with the responsibility – political, legal, moral – for its aggression against Ukraine. But in its historical aspect, this responsibility should have an expansive interpretation and include responsibility for other nations that were in the past or presently are objects of Russia’s colonial influence.

Russia’s armed attack against Ukraine is not an excess caused by the personal madness of its commander-in-chief, Vladimir Putin. Rather, it is a relapse into the imperialist policy that Russia has pursued for centuries toward Ukraine and other subjugated nations. This policy has not yet been recognised even by the majority of liberal-minded Russian citizens in terms of its systematic nature, duration and severity of long-term consequences. We can say that it is implicitly embedded even in the Russian high culture, which seems to be traditionally opposed to the state – embedded as a hidden or explicit complex of superiority, linguistic arrogance, learned and unlearned ignorance of the history and culture of neighbouring peoples, which generates a “natural” idea of their insignificance, secondary importance, non-subjectivity, and natural belonging to the historical destiny of Russia.

If we look from this point of view at the Russian cultural landscape, which, again, has been formed over centuries, it will be extremely difficult to find a clue, a starting point, a symbol on which to build the concept of responsibility for Ukraine. Of course, the armed aggression that began in 2014, the annexation of Ukrainian territories, and the numerous grave war crimes committed by the Russian army in and of themselves call for responsibility; the spilled Ukrainian blood can neither be forgiven nor forgotten. But it is important – first of all for Russian citizens themselves – to establish the continuity of the criminal policy, to recognise its historical dimension, its heavy inheritance passed on from generation to generation, which now creates the mental fertile soil for the aggravated genocidal sentiments spread by propaganda.

Unfortunately, Russian history (as it is taught in mass educational institutions), which is generally a narrative of “peaceful conquest of lands” or voluntary unification of peoples under the aegis of the Russian state, serves exactly the opposite purpose. Russian culture, with rare exceptions such as Leo Tolstoy’s novella Hadji Murat, ignores or uncritically exploits the colonial aspect of Russia’s expansion, glorifying the enlightening mission of colonisers bringing progress to “backward” regions. For example, there are thousands of streets in Russia named after Ukrainian cities, hundreds of architectural structures (railway stations, bridges, buildings) whose names impose the idea of Ukraine’s dependence and conflict-free unity of Russian and Ukrainian nations.

And there are arguably only two cultural signs in Russia that speak of conflict and symbolise past Russian crimes against Ukraine.

The first is a cross in the Levashovo Memorial Cemetery, a Soviet execution site near St. Petersburg, erected in 2001 on the initiative of the city’s Ukrainian civic institutions. In February 2023, unknown assailants sawed off part of the plaque, removing the words “innocently murdered” from it but leaving “eternal memory to the Ukrainians”: a literal amputation of historical memory and responsibility.1

The second, more artistically and historically significant monument, however, is far away in the Russian North, out of sight of most. The limestone Cossack cross, erected in 2005 and inscribed “To the Murdered Sons of Ukraine”, is located in the Karelian district of Sandarmokh, where more than 6,000 people were executed by the Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (the Soviet interior ministry better known by its Russian acronym NKVD) in 1937-1938.

About 200 of them were Ukrainian cultural figures – writers, playwrights, scientists, arrested in the 1930s in a series of interrelated cases fabricated by the Soviet security agencies (most significantly, the case of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine and the case of the Ukrainian Military Organisation), accused in one or another variation of Ukrainian nationalism, arrested and sent to the Solovki prison camp to serve time, only to be convicted again by NKVD troikas and executed in 1937.2

Sandarmokh is the scene of a crime – Soviet in form (mass execution), but imperial in content: the destruction of the cultural elite of the subjugated people, the bearers and conductors of the idea of cultural self-esteem and independence, the idea of emancipation.

“To eradicate all manifestations of Ukrainian nationality, national life and culture, to liquidate educational and scientific cadres” – this is how the Ukrainian dissident, writer and critic Ivan Dzyuba described the tasks of Stalin’s anti-Ukrainian campaign in his famous book Internationalism or Russification?,3 for which he was persecuted by the Soviet Committee for State Security (better known by its Russian acronym KGB).

And it is no coincidence that the language of Russian military propaganda today is virtually identical to the language of summary executions in the 1930s: in Stalin’s time, the phrase “Ukrainian nationalist” was itself a stigma and a punishment – and today Russian TV channels report on the “extermination of Ukrainian nationalists” in Defense Ministry briefings with the same degree of self-explanatory linguistic impudence: if a nationalist, then he or she deserves to die.

The case of Yury Dmitriev

As a place of remembrance, Sandarmokh became widely known in Russia and abroad because of the ominous series of events that began after Russia’s attack against Ukraine in 2014.

In previous years, the commemoration on 5 August (the day the executions began in 1937) was always attended by large Ukrainian delegations – observers could see diplomats and yellow and blue Ukrainian flags, and hear Ukrainian speech.

However, in the context of the war, the Ukrainian monument in Sandarmokh and the Ukrainian history of Sandarmokh turned into the witness of prosecution, evidence of the persistent, systemic nature of Russia’s repressive policies against Ukraine.

In 2015, in the presence of officials, Yury Dmitriev, a researcher of the Soviet network of forced labour camps (better known by its Russian acronym Gulag)4 and the head of the Karelian Memorial human rights organisation, spoke about the war in eastern Ukraine – a war that Russia did not acknowledge and waged in secret.5 Dmitriev also spoke about the victims of that war, whose names will one day be made public – as in Sandarmokh – although their killers hope that oblivion will be eternal. He spoke aloud: “My dear brothers and sisters, something must be done with this regime”.6

It was apparently in 2015 when security services started working on Dmitriev. He crossed the red line: he pointed out the monstrous continuity of crimes.

In July 2016, Petrozavodsk historians Yury Kilin and Sergey Verigin unexpectedly came up with an outlandish hypothesis implying that it was not Gulag prisoners who had been buried in Sandarmokh, but Soviet prisoners of war shot by the Finnish army during the Second World War.7 The same year, Russian officials ignored the day of remembrance on 5 August, for the first time since the memorial cemetery was established.

And in December 2016, Dmitriev was arrested. The charges – production of child pornography and, later, sexual misconduct against a minor – were chosen precisely to not only send Dmitriev to prison for a long time, but also to irrevocably blacken his name, compromise Sandarmokh as much as possible as a place of remembrance, and push people away.

In 2018, the Russian Military Historical Society (also known by its Russian acronym RVIO) conducted excavations of dubious legality in Sandarmokh. The RVIO was founded in 2012 with the participation of Russian Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky and President Vladimir Putin, and, since then, acted as a state commissioner in the field of historical memory. During the 2018 excavations in Sandarmokh, several bodies from the mass graves were removed and taken to an unknown place. In 2019, the RVIO publicly announced that the excavation data confirmed Kilin’s and Verigin’s theory.8

At the federal level, the authorities used the case against Dmitriev to discredit the Memorial historical and educational society, and independent research into Soviet crimes as such; to cast a shadow over Sandarmokh and other mass execution sites, questioning their authenticity; and to intimidate activists.

Dmitriev’s trial lasted around five years; the judges changed, the trial began anew, and finally Dmitriev, initially acquitted, was sentenced to 15 years and sent to Mordovia, to Dubravlag, another region of the country with a long and horrific penal history, in fact one of the surviving “islands” of the Soviet “Gulag Archipelago”,9 as Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn put it.10

Given his age and the sanitary conditions of Russian penal colonies, Dmitriev’s imprisonment is legalised murder.

The forest of the executed peoples

In a paradoxical and sad way, it was Dmitriev’s arrest and the public campaign in his defence that revealed Sandarmokh and its story for the Russian liberal public.

Yury Dmitriev and his colleagues at the St. Petersburg branch of Memorial, Irina Flige and Veniamin Ioffe, discovered Sandarmokh in 1997. That was one of the rare cases in which neither the KGB nor Russia’s Federal Security Service “legalised” a special site to pre-empt researchers, but the researchers themselves, despite the regime of secrecy, found their way to the archival data and then made a discovery on the ground. The memorial complex was created far from big cities, in the taiga.11

Among those executed in Sandarmokh were 1,111 prisoners of the Solovki prison camp – the so-called “first Solovki intake” (pervy Solovetsky etap) that consisted of people accused of counterrevolutionary activities while in prison.

It was the search for that “intake” that eventually led Dmitriev and his colleagues to Sandarmokh; it was in that “intake” that most of the Ukrainian prisoners included in the “Sandarmokh List” compiled by Ukrainian historians and journalists had been killed.

That unfortunate Solovki “intake” was a kind of “time machine”, a reliquary of the victims of the earlier repressive campaigns who were arrested in the early and mid-1930s – campaigns with their own, milder (compared to the late 1930s) degree of villainy.

The Ukrainians murdered in Sandarmokh – writers, scientists, artists, painters – generally fell as a collective victim of the Soviet authorities’ turn in the late 1920s from the policy of korenizatsiya that encouraged nation-building to the criminalisation of nationalism and the chauvinistic imperial agenda; a turn that tactically coincided with the Soviet policy of collectivisation and operations against the former elites in the service of the Soviet regime.

As early as in the middle of the 20th century, the Ukrainian literary scholar Yury Lavrynenko proposed the general term “Executed Renaissance” (in Ukrainian: Rozstrilyane vidrodzhennia)12 to refer to all members of the Ukrainian creative community who had been executed in various places, sent to camps, silenced under the pressure of circumstances.

However, Ukraine and Ukrainians were by no means the only Soviet nation to suffer in this way. Virtually every Sovietised people, large or small, experienced its own “executed renaissance”. Unfortunately, in the common memory of Russia, these atrocities are very rarely identified as a special type of genocidal crime – crimes against national cultures and languages at a vulnerable stage of development, crimes against the future of nations – represented by their cultural leaders, geniuses of language, masters of art. And here it is important to understand and establish the responsibility of the Russian culture and the Russian language, because those crimes were de facto committed in their favour, because the national was eventually replaced by the Russian as something supranational, universal.

Belarusians and Ukrainians, Tatars and Udmurts, Karelians – if we look closely at the “early” period of repressions, in the late 1920s – early 1930s, we will find in the history of each nation a massive criminal case cooked up by the Soviet state security organs according to one and the same scheme – a case of some non-existent “centre” or “organisation” allegedly linking the national intelligentsia to counterrevolutionary aims on the basis of “bourgeois nationalism”. And in each of those almost identical cases, the accused, who would eventually become the victim, was not the pre-revolutionary, but the Soviet – in fact, the new – cultural elite, that bought into the early promises of the Bolsheviks to turn away from imperial chauvinism and began creating foundations of national cultures: to do ethnography, to compile dictionaries and write textbooks, to reform languages, to write poetry, prose and drama, to launch mass media – in national languages, to make up for what had been lacking, what had not been created in earlier times.

If one reads the list of the “first Solovki intake”, one will find, besides the names of Ukrainians, which are strikingly numerous, other names from the 1930s. There are, for example, names of cultural figures from Tatarstan and Bashkiria who were arrested on the charges of belonging to the “counterrevolutionary nationalist organisation” of Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev; Belarusians who were sent to Solovki in the cases of the Belarusian Peasant-Workers’ Community and the Belarusian National Centre; Finns from the Russian North who were arrested in the “case of the Finnish General Staff”; Udmurt and Komi people, victims of the case of the “Union for the Liberation of Finnish Peoples”. Their names and their biographies are a bitter confirmation of the fact that the mass murder of Ukrainian cultural figures in Sandarmokh was not an exception, not an excess, but a direct consequence of the systematic policy of the Soviet leadership aimed at suppressing the national development and self-consciousness of subjugated peoples, which gave rise to dozens of similar repressive processes and dozens of crime scenes.

The fundamental difference of Sandarmokh is that this place of memory was originally developed in a special way – thanks to Yury Dmitriev and his colleagues.

In Sandarmokh, there is no single, typologically recognisable monument, no wall featuring all the names of the dead. Sandarmokh was developed and purposefully organised as a forest of memory, a forest of individual names on plaques – and individual national monuments erected by countries and national communities. Representatives of about 50 nationalities are buried here, and, over the years, about 450 monuments and memorial signs were erected, including the Cossack cross “To the murdered sons of Ukraine”.13

One could say that Sandarmokh is divided along the national spectrum, and here what is hidden elsewhere becomes visible: not only the class-based, but also the colonial, national character of Soviet crimes, inheriting the chauvinist policies of the Russian Empire.

A symbol of colonial violence

Sandarmokh is located in the Russian North, near the city of Medvezhyegorsk in the Russian Republic of Karelia. From there to the Ukrainian border is at least 1,200 kilometres, roughly the distance from Rome to Brussels. The area itself, though in the orbit of Russian interests for centuries, is an annexed, colonised territory long contested by Russia and Sweden. During the Russian Civil War, there was a mass national uprising of Karelian Finns, which was crushed by the Soviet Red Army. Thus, Sandarmokh is located on the territory where the indigenous population was, first, colonised and, second, hardly shared the state-wide political goals of repressions (Karelians themselves suffered during the period of collectivisation).

Sandarmokh as a topos is the result of the invasion of the will of the Russian state that chose this spot as a place of mass destruction, subverted its historical innocence and cursed this forest district to become a place of execution; the will of the state that came to the North in the form of the Gulag camps, in the form of the yet another stage of the colossal project of internal colonisation.14

In a sense, the national monuments standing in Sandarmokh do not belong there. The place was practically chosen by fate: the executioners could have chosen any other area for their black deed – the taiga is vast. The national monuments of Sandarmokh are, in a way, cenotaphs, although they stand exactly at the place of death.

But it is not the local taiga forest that has suffered losses. Death of Ukrainian artists, Tatar writers, Udmurt ethnographers orphaned and robbed other lands – their homelands.

The national monuments of Sandarmokh are a kind of a map, a compact model, a universe of memory in a compression point, which one day will have to be unfolded – on a nationwide scale. Because down to the present – and the criminal war against Ukraine and the denial of Ukraine’s historical and cultural subjectivity are the best proof of this – Russia, especially Russian-speaking Russia, still does not realise to what extent imperial consciousness determines its political structure, to what extent institutionalised colonial violence is the unnoticed reality of today.

Two wars against Chechnya. The war against Georgia. The war against Ukraine. These are visible proofs of Russia’s aggressive, invasive, revanchist politics. But even in the minds of opposition-minded Russians, these are disparate episodes rather than successive stages of a single plot: the initial suppression of national emancipation within the borders of the Russian state – and the transfer of repressive practices outward, from the soft “absorption”, “erasure” of the national subjectivity of Belarus – to the attempted genocidal destruction of Ukraine.

However, wars are still recognised as crimes by Russian citizens with a sense of civic responsibility. Much less attention is paid to – and fewer questions are raised about – the internal Russian practices of institutional suppression of national cultures, the daily routine of cultural inequality that creates a chauvinistic tone, a flux of Russian-speaking culture that goes unnoticed by its bearers.

Today, soldiers from Russia’s national republics are fighting in Ukraine, and, as military experts point out, their participation is disproportionately high.15 De facto, Russia is cynically exploiting colonised nations – Tatars, Buryats, Kalmyks, Chechens, and many others – just as empires of the past exploited subjugated peoples in their armies (French Zouaves or British Gurkhas).

The difference is that the soldiers of the national republics of Russia are fighting, as the official propaganda claims, for the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine, allegedly oppressed and deprived of language rights.

This is a classic example of accusation in the mirror, because in reality it was the national republics of the Russian Federation that lost a lot in 2018 when the Russian parliament adopted, at the behest of Vladimir Putin, the law “On native languages”16 that effectively made the study of national languages in the schools of the respective regions voluntary (previously, it was compulsory). It is obvious that the law provokes language migration, rejection of the local language in favour of the supranational one, and seriously violates cultural autonomies.17

However, the issue of teaching national languages has not become part of the opposition agenda because, unfortunately, the problems of national minorities as such are not part of it.

And the situation itself is partly reminiscent of the 1930s in the USSR – a period of imperial reaction after a period of national “revivals” in the 1920s. And in this sense, not only does Sandarmokh preserve memory – it also represents a map of ongoing, simmering conflicts: the questions raised by the national cultures that were destroyed here – questions of national identity, autonomy, history, linguistic and political rights – remain extremist and dangerous in the eyes of the Russian state as they question the existing system of power based on the absolute domination of the centre – not only fiscal, cultural and political, but also linguistic.

This logic suggests that any national movement aimed at emancipation from Moscow, from Russia, from the centre, is inherently sinful, inherently guilty of fascism or Nazism, drawing its strength and ideas from them.

“The black sperm of fascism has spilled on Kiev, the mother of Russian cities”, wrote Alexander Prokhanov, the mad anti-Ukrainian hate monger and ideologue of the “Russian world”, in May 2014.18

Today, Russia is waging a criminal war against Ukraine, declaring “denazification” as an objective of the war and accusing Ukrainians of Nazism. And the monuments of Sandarmokh testify that this is by no means the latest invention of propaganda.

The perception of any kind of nationalism, the desire for national self-construction as a sin, as an existential threat to the polysynthetic whole of the Russian Federation assembled by violence and force, permeates the historical consciousness and political culture of Russian citizens. This perception is not properly reflected on, not fully realised, and that is why Russian state propaganda is so successful. It appeals to an unconditional ideological reflex, nurtured by generations of those who lived in a political system in which the declared, folklorised “selfhood” (samost’) of peoples was just a façade of national policy that concealed imperialist domination and repressive practices.

In the early 1990s, Russia, Russians, and Russian speakers had a chance to make sense of their own dual situation: a people that was the victim of the imperialist project, surrendering its freedoms to the goals of an authoritarian state, and a people that was the aggressor, bringing unfreedom to others, both internally and externally. However, in fear of the red, communist revanche in the 1990s, Russian intellectuals overlooked the imperialist revanche.

Today, when Russian troops have openly invaded Ukraine, and the names of Ukrainian cities and towns are becoming the names of new atrocities, the responsibility of Russian intellectuals is – among other tasks – not only to condemn the immeasurable evil harm done to Ukraine and Ukrainians, but to examine and finally recognise the genealogy of this evil, which, rather than being misplaced or irrational, is the “dark side” of Russian social and political life.

To finally recognise that the crimes committed against Ukraine today are directly and unconditionally connected with the crimes of the past: with the defarming (raskulachivanie) of the Ukrainian peasantry and the Holodomor (man-made famine), with the destruction of Ukrainian cultural elites, including in Sandarmokh, with the suppression of the national armed resistance to the Soviet rule, with the suppression of the national dissident movement in the 1960-1970s and later.

To recognise that not only the victims of Irpin, Bucha and Mariupol, but also the victims of other times – all those who were robbed of culture, language and life in the name of the integrity of the Russian state – are demanding justice.

The seal of disintegration

The USSR could not be reborn in Kyiv, Chișinău, or Tbilisi, but only in Moscow.

Because only in Russia, with its centuries-old imperial heritage, does this fundamental, existential fear of disintegration, this fear of separation exist. And the entire Russian authoritarian state, in all its incarnations, is a frozen, bastioned, prison-walled emanation of that fear.

And that is why an independent Ukraine will never be neutral for the Russian conservative consciousness, no matter how many pacts of neutrality are signed. It will always remain a source of threat and an object of desire, because the very fact of its existence will prove that it is possible to live without Russia, outside of Russia. And this is not a catastrophe, as Vladimir Putin believes, but a norm.

This fear of disintegration is the dark daemon of Russian statehood, its inspiration. And in it lies Russia’s historical destiny, its fate.

This is the fear of a guilty conscience, the fear of illegal, criminal possession, the fear of karma. It drives new crimes – otherwise it will be necessary to recognise the old ones, to revise history, culture and identity, to assume liability for the conquest and subjugation of other peoples.

Many people fell victim to this fear in the 20th century: national deportations, expulsions, cleansing operations, suppression of national resistance movements, Russification. Periods of disintegration, as in the Russian Civil War or Perestroika, were followed by periods of revanche, as after 1945 or in 2014; but Ukraine’s courageous resistance today proves that revanche is impossible – it is only conquest, destruction and occupation that are possible.

Without reckoning with the past

In the 1990s, Russia was unable to overcome its past. First of all, because intellectual elites saw the Soviet totalitarian regime as a deviation, as an unfortunate disease, the elimination of which through the supposedly bloodless collapse of the USSR seemingly guaranteed a return to the right historical path.

Already the first invasion of Chechnya in December 1994, which repeated the pattern of the Caucasian colonial wars waged by the Russian Empire in the 19th century, should have raised the question of the true nature of the new Russian state. But again, the war launched by President Boris Yeltsin, although criticised by intellectuals who called it, for example, “a wild anachronism”,19 was perceived as an isolated case, a mistake, rather than as evidence that the very historical-political structure of the Russian Federation, burdened as it was by the weight of colonial violence, contained the virtually inevitable preconditions for imperial revanche.

Post-Soviet Russia, while paying lip service to democratic principles and the desire to “strive for real guarantees of the rule of law and human rights”, as enshrined in the law “On rehabilitation of victims of political repression” passed on 18 October 1991,20 has in fact not fully dismantled the main instrument of Soviet violence – the KGB.21 Having retained structural, cadre and symbolic continuity, the security services became the leading force of anti-democratic reaction. After all, throughout the Soviet period, one of the main tasks of the state security agencies was to suppress impulses for national emancipation and movements for national independence, both in the republics of the USSR and in the republics within the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

Of course, the late Soviet colonial policies were implemented with the participation of many actors: educational, cultural, and social. The same Ivan Dzyuba describes its mechanisms in detail in the above-mentioned article: Russification, migration and labour policies, cultural assimilation, ideology and propaganda, falsification of history, compulsory military service, professional barriers related to language skills, economic exploitation, etc.22

All of these mechanisms were embedded in the regular functioning of Soviet institutions. Indeed, Dzyuba argued, in particular, that substitution and replacement of the national in favour of the supranational Russian took place imperceptibly, as if by the force of life itself, and it required a special effort of attention to register these changes.

In part, the KGB’s activities against national activists can be compared to “social engineering” due to the important role played by the methods of “proactive management” (profilaktika), i.e. prevention of ideological deviations through pre-trial measures, such as exerting influence (pressure) through agents, “preventive talks” with individuals or groups, and open publications in the media.23

It was the KGB that was responsible for the openly repressive component of the Soviet colonial policies: for the creation and dissemination of the image of “nationalists” as unconditional enemies of the Soviet system, and for aggressive operational measures against them: surveillance, “measures of disruption” aimed at discreditation of individuals and disintegration of groups, arrests, trials, and sentences.

In other words, the KGB (and its predecessors) possessed a punitive function based on the demonisation and alienation of the national as an unconditional danger, as a hostile Other that threatened the integrity of the state.

This direction of Soviet punitive policy was almost overlooked in the attempts to analyse the Soviet totalitarian legacy in the 1990s. At that time, the national policy of the Russian state was already de facto following the trajectory set by the KGB.

The ideological justifications for Russia’s ongoing criminal war against Ukraine are also literally borrowed from the Soviet arsenal. The cornerstone of the ideological rhetoric is the notion of “Ukrainian nationalism” interpreted as an existential threat to Russia, and “Nazism”, supposedly inherent to this nationalism because of its historical genealogy and collaboration of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) with Germany during the Second World War.

Here one recognises the old KGB technique, which, in the case of Ukraine, tried to equate the terms “nationalism” and “Nazism”. The main emphasis in the KGB’s public information and propaganda work has always been on denigrating and “exposing”, first of all, the OUN-UPA in the phase of armed confrontation, which, by the very nature of armed conflict, provided the most powerful and sinister images of the opponent. The “exposure” of later nationalist groups, dissidents and social movements was generally carried out by linking them politically or intellectually to the structures of the OUN-UPA and through forced identification of their goals.24

Accordingly, the negative image of the OUN-UPA in the Soviet Union functioned as a common denominator that allowed political differences to be ignored and any manifestations of national, emancipatory sentiments to be given an unambiguously negative meaning. The same denominator was an integral part of the anti-Ukrainian content, linking it to a recognisable historical narrative.

In this context, the Ukrainian graves of Sandarmokh and the fates of Ukrainian intellectuals who died there have become undesirable witnesses for the contemporary Russian authorities, as they manifest the long trend of anti-Ukrainian repressions. Both the graves of Sandarmokh and Sandarmokh itself, as a place of long historical memory, could become the point where public consciousness turns from neglect and denial to the difficult recognition of historical responsibility for the very nature and structure of the Russian state and society that made possible not only the war against Ukraine, but also all other militaristic, political, cultural relapses of colonial violence.

P.S.

Language is power.

Language is secrecy.

The KGB department in the special Soviet camp Dubravlag, where political prisoners were held and where Yury Dmitriev is now imprisoned, secretly recorded conversations that took place in the meeting room.

Conversations in Russian were immediately placed in operational dossiers and used against prisoners.

But tapes with conversations in other languages, such as Ukrainian, Lithuanian or Estonian, were sent for transcription to KGB offices in respective republics by special couriers, so what went on between the two people in the meeting room remained a mystery for weeks.

Language served as the last defence, as a veil in a niche that had no curtain or cover.

Language was a metaphor for the nocturnal darkness of love, a direct expression of intimacy; in language, freedom lived, albeit briefly, no longer than the age of the butterfly.

Language offers a possibility to read the other; language also offers a possibility to not be read by the other. Joseph Brodsky, in his infamous poem “On the independence of Ukraine”,25 behaves not like a poet, but like a suzerain of language who has learned that a province has been taken from him: he feels a personal insult, a damage to his personal power.

That is why it is so important for us, who write and speak Russian today, that the Ukrainian graves of Sandarmokh speak. That the terrible fate of the artists of the Ukrainian language who were executed there, the terrible report of a stolen future, were realised as part of the continuing tragedy of Russia’s aspirations to control Ukraine, as an aggravation of today’s guilt – and a call for taking responsibility.

Translated from Russian into English by the Centre for Democratic Integrity.

An earlier version of this article was published in German in Osteuropa: “Wenn die Gräber sprechen. Sandarmoch – Gedenkort kolonialer Gewalt”.

Endnotes

-

- “Vechnaya pamyat’ ukraintsam. Kto tsenzuriruet memorialy v Levashovskoy pustoshi?”, Fontanka, 25 February (2023), https://www.fontanka.ru/2023/02/25/72088868/.

- “Spysok Sandarmokhu”, Wikipedia, https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Список_Сандармоху.

- The book was written in 1965 and originally spread in samizdat. It was officially published in 1968, see Ivan Dzyuba, Internatsionalizm chy rusyfikatsiya? (Munich: Suchasnist’, 1968). Quoted here from the English language publication: Ivan Dzyuba, Internationalism or Russification? A Study in the Soviet Nationalities Problem (New York: Monad Press, 1974), p. 130.

- See more in Galina Mikhailovna Ivanova, Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System (London: Routledge, 2000); Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History (New York: Doubleday, 2003).

- “O prigovore Yuriyu Dmitrievu”, Memorial, 29 September (2020), https://www.memo.ru/en-us/memorial/departments/intermemorial/news/465.

- Nikita Girin, “Lyudoedy zakonchili s zakuskami”, Novaya gazeta, 14 December (2021), https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2021/12/14/liudoedy-zakonchili-s-zakuskami.

- Anna Yarovaya, “Rewriting Sandarmokh: Who Is Trying to Alter the History of Mass Executions and Burials in Karelia, and Why”, The Russian Reader, 29 December (2017), https://therussianreader.com/2017/12/29/anna-yarovaya-rewriting-sandarmokh/.

- Irina Tumakova, “Rvy i RVIO”, Novaya gazeta, 12 June (2019), https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2019/06/12/80865-rvy-i-rvio.

- Irina Galkova, “Yuri Dmitriev’s GULAG”, Eurozine, 16 June (2023), https://www.eurozine.com/yuri-dmitrievs-gulag/.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation (New York: Harper & Row, 1974).

- Sergei Lebedev, “On Yuri Dmitriev”, Eurozine, 10 November (2017), https://www.eurozine.com/on-yuri-dmitriev/.

- Yurii Lavrinenko (ed.), Rozstrilyane vidrodzhennya: antologiya 1917-1933: poeziya, proza, drama, esey (Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1959).

- “Memorial’noe kladbishche Sandormokh”, https://sand.mapofmemory.org.

- Aleksandr Etkind, Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011).

- Paul Goble, “Ukrainian War Unsettles Russian Regions and Non-Russian Republics”, The Jamestown Foundation, 8 March (2022), https://jamestown.org/program/ukrainian-war-unsettles-russian-regions-and-non-russian-republics/.

- “O vnesenii izmeneniy v stat’i 11 i 14 Federal’nogo zakona ‘Ob obrazovanii v Rossiyskoy Federatsii’”, Gosudarstvennaya duma, https://web.archive.org/web/20190927002443/https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/438863-7.

- “Russian Bill Threatens Native Languages”, Language Magazine, 10 November (2018), https://www.languagemagazine.com/2018/11/10/russian-bill-threatens-native-languages/; Mihail Kaplan, “How Russian State Pressure on Regional Languages Is Sparking Civic Activism in the North Caucasus”, openDemocracy, 31 May (2018), https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/pressure-on-regional-languages-is-sparking-civic-activism-in-the-north-caucasus/.

- Aleksandr Prokhanov, “Odinnadtsaty stalinsky udar”, Izvestiya, 5 May (2014), https://iz.ru/news/570303.

- “Voyna v Chechne. ‘Izvestiya’ publikuyut prizyv intelligentsii ostanovit’ voynu”, Rastsvet rossiyskikh SMI, http://www.yeltsinmedia.com/events/jan-6-1996/.

- “Zakon Rossiyskoy Sovetskoy Federativnoy Sotsialisticheckoy Respubliki ‘O reabilitatsii zhertv politicheskikh repressiy’”, Fond Aleksandra N. Yakovleva, https://www.alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues-doc/68292.

- Evgenia Lezina, XX vek: prorabotka proshlogo (Moscow: NLO, 2021), pp. 457-481.

- See Dzyuba, Internationalism or Russification?

- Evgenia Lezina, “From Mass Terror to Mass Social Control: The Soviet Secret Police’s New Roles and Functions in the Early Post-Stalin Era”, in Immo Rebitschek, Aaron Benyamin Retish (eds), Social Control under Stalin and Khrushchev: The Phantom of a Well-Ordered State (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2023), pp. 263-297.

- Evgenia Lezina, “Tsel’yu KGB bylo priravnyat’ ukrainskoe natsional’noe dvizhenie k fashizmu”, Republic, 15 January (2023), https://republic.ru/posts/106830.

- “On the Independence of Ukraine”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Independence_of_Ukraine. See also Olga Bertelsen, “Joseph Brodsky’s Imperial Consciousness”, Scripta Historica, No. 21 (2015), pp. 263-289, https://www.academia.edu/26054913/Joseph_Brodsky_s_Imperial_Consciousness.