Between Paranoia and Apathy: Russian Diplomats, Conspiracy Theories, and Ukraine

Boris Bondarev

Former Russian diplomat (2002–2022), who worked for the Russian permanent mission to the United Nations Office at Geneva from 2019 until his resignation in May 2022 in protest over the Russian invasion of Ukraine

26 August 2024

[This article is part of our research initiative “Russia’s Project ‘Anti-Ukraine’”]

Conspiratorial thinking, i.e. the search for someone’s evil intent everywhere and the belief that, as Woland said in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “a brick will never drop on anyone’s head just out of the blue”,1 is characteristic of people who work in the area of combating various threats. First and foremost, these are officers of special services whose duties include counter-intelligence and secret police functions. Members of Russia’s special services, such as the Foreign Intelligence Service (Sluzhba vneshney razvedki, SVR) and the Federal Security Service (Federal’naya sluzhba bezopasnosti, FSB), have largely inherited this conspiratorial mindset from their senior colleagues in the Soviet KGB.

SVR and FSB officers receive their first indoctrination in conspiratorial thinking and the conspiratorial worldview when they begin their training in specialised educational institutions. Then, as they enter the workplace and communicate with their senior colleagues, they become increasingly convinced that there are conspiracies and malevolent intentions everywhere that need to be found and suppressed. Since a critical approach to information is not considered a virtue in such departments (except for some technical cases), their employees rarely question the very idea of the omnipotence of malice and its primacy. Blue-sky thinking unfettered by the limits of logic easily becomes grotesque: we are encircled by enemies, they are everywhere, and above all, all negative experiences in our lives, whether on a national or personal level, are the result of someone else’s evil will.

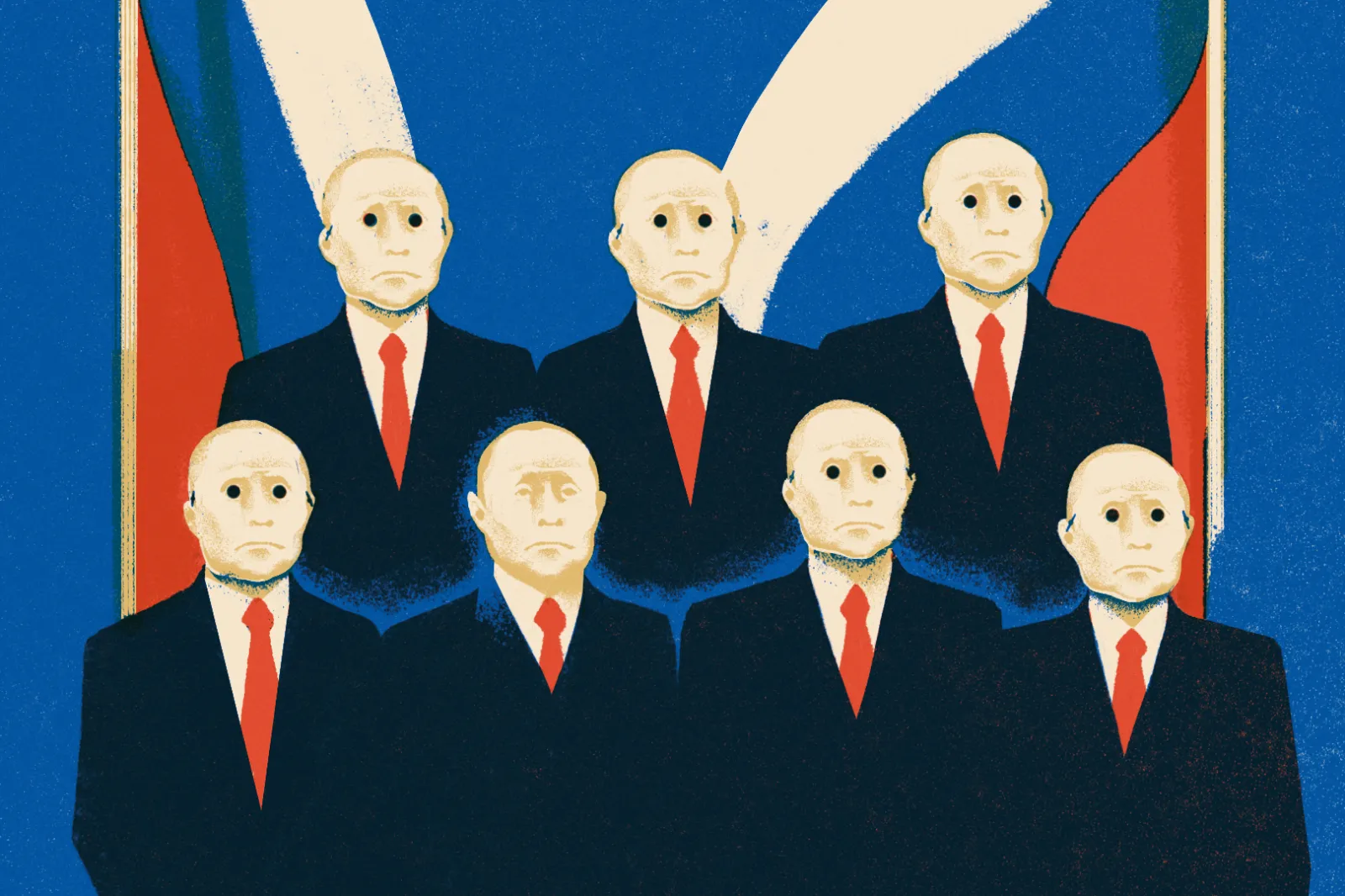

This reaches the point of complete absurdity when even the country’s leadership, which consists of former KGB officers, indeed assumes that Western countries – our eternal enemies – exist only to make trouble for Russia. They have no other function and cannot have any interests of their own. Hence the resentment against the West: it supposedly makes no reckoning of our interests not because it has its own interests to advance, but because the West is simply malicious and dislikes Russia in principle.

But when we talk about the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), which deals with foreign policy, the picture is different. It is precisely because of the specific nature of their work that diplomats are much more open to the world. In contrast to the regime’s “attack dogs”, diplomats need to find something in common in the positions of their country and the countries that they work with. They need to be more open and broad-minded, which is not necessarily the case with counter-intelligence or the silencing of dissent. Diplomats are to see, first and foremost, the interests of their partners and to try to accommodate those interests, rather than seeing them as implicitly hostile.

In the 1990s, as the rapprochement with the West became more tangible, there were also changes in the Foreign Ministry that had little to do with ideology. In the early 1990s, when it became almost impossible to live on the salary of an MFA employee, many of the most motivated and ambitious diplomats left. Those who remained proved to be more inert and less inclined to critical thinking. This worked to their advantage, as there was a huge staffing gap at the middle and senior levels of the MFA, which explains the rapid career rise of today’s MFA leadership – they were in the right place at the right time.

This natural selection has perpetuated the qualities of malleability, servility and fear of responsibility inherent in the diplomatic service. People who showed loyalty and commitment to their superiors were rewarded with privileges, while young people quickly realised that the expression of personal opinions was not welcome. The situation deteriorated further in the 2000s, with many young people using their jobs just to earn money on their first posting and then leave for the private sector.

This certainly contributed to the fact that, in the 2000s, the MFA never saw itself as a political actor, or, more precisely, as a co-author of foreign policy – an idea factory that would meaningfully participate in the formulation of foreign policy goals and objectives. Both Igor Ivanov (Russia’s Foreign Minister in 1998-2004) and Sergei Lavrov (Russian Foreign Minister since 2004) reduced the role of the Foreign Ministry to that of a purely technical body, responsible only for implementing the decisions of the country’s top leadership.

A case in point was Ivanov’s reaction to the famous “March on Pristina” in 1999, a military operation by Russian forces in Yugoslavia to seize Slatina airport in Kosovo. The operation was ordered by Russian President Boris Yeltsin, who did not even see fit to inform his foreign minister. When journalists questioned Igor Ivanov live on air the day after the “march”, he simply did not know what had happened. The only real way out of that situation, which would allow the minister and the Foreign Ministry to save face, would be to tender his resignation. After all, what was the point of having a foreign minister if his professional opinion was not taken into account when crucial foreign policy decisions fraught with grave consequences were made?

A similar incident occurred in 2011 during the First Libyan Civil War, when the leadership of the Foreign Ministry and designated staff, including Russia’s Ambassador to Libya, Vladimir Chamov, categorically opposed President Dmitry Medvedev’s position of agreeing to the UN Security Council resolution on a no-fly zone.2

Chamov wrote cables harshly criticising this policy. As a result of the last telegram, in which, according to rumours circulating in the Foreign Ministry, he directly raised the issue of the Kremlin’s betrayal of national interests,3 Medvedev was outraged and wrote a resolution saying that if the ambassador did not understand the president’s policy, he had no business in his post. Chamov was recalled, and although Lavrov and other superiors in the Foreign Ministry agreed with Chamov, they did not argue with Medvedev.

The solution would have been a collective walkout of Foreign Ministry high officials, led by the minister, who would have resigned. This would have saved face and shown that the Foreign Ministry employed people who were capable of having and expressing their opinions. That did not happen: Lavrov unlikely thought of such a step, but even if such thoughts did cross his mind, he probably quickly dismissed them, because his status was more important to him. Many Foreign Ministry staff do not see this as a problem and think that this is the way things should be. They see it as normal to be in complete agreement with the leadership and not have an opinion of their own.

Similar trends have been observed in relations with Ukraine. In the 1990s, Foreign Ministry staff had very different opinions about Ukraine: in informal surroundings, some were shouting that Russia should reclaim Ukraine, others did not care. Official Moscow became more interested in Ukraine in 2004 after the so-called “Orange Revolution”, and many were, in fact, irritated by the abundance of news about Ukraine on television.

But it was one thing to grumble within the team and quite another to express one’s thoughts publicly. The MFA had no serious objections to Moscow’s policies on Ukraine, and the staff followed the leadership’s instructions, confident that the policies were right. Exactly why the policies were right was of no concern to them.

Many Soviet diplomats do not like questions about why they supported the party line so ardently in different periods, whether it was the struggle against “American imperialism” or Perestroika. They always followed instructions and did not think about the meaning of policies. In the 1970s, they promoted “détente”; in the first half of the 1980s, they formidably opposed “American warmongering” and “Reagan’s militarism”; in the second half of the 1980s, they signed disarmament agreements with that same Reagan; in the 1990s, they were passionately friendly to the West; and, under Putin, they broke with the West just as passionately. And yet they never questioned the reasons for such dramatic volte-faces and to what extent they reflected the objective needs of the country and society. Russian foreign policy has always been shaped by a narrow circle of unaccountable top government officials whose views did not pass through the “sieve” of public discussions and parliamentary hearings, as is typical in democratic systems.

However, this can hardly be attributed to conspiratorial thinking, and it would be incorrect to reproach the MFA for developing conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories in the MFA are a phenomenon borrowed and adopted from intelligence officers with whom diplomats work closely, and especially from the higher echelons of power filled with former KGB officers professing the most backward concepts of the world order. The Foreign Ministry simply goes along with it, unwilling to quarrel and afraid to defend its point of view.

Curiously, however, when it comes to vested interests of the leadership or departmental interests, the MFA is capable of strong resistance, using a rich arsenal of bureaucratic tools. Contrary to the widespread belief in the omnipotence of certain agencies, such as the FSB, the Presidential Administration or the Security Council apparatus (formally a subdivision of the Presidential Administration), interagency conflicts with the MFA have not always ended in their favour. On matters of state strategy, however, senior diplomats prefer not to contradict people in uniform. This became especially the case after the start of the “Special Military Operation”.

At the same time, within the framework of their work, the diplomatic service maintained a greater degree of common sense and foresight than the security services.

In 2014, the joint Russian-Ukrainian “Dnepr” project that converted the decommissioned R-36 Voevoda (NATO reporting name: SS-18 Satan) intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) into medium-lift space launch vehicles came to an end. However, the idea of such a conversion, which would kill two birds with one stone – putting a payload into orbit and disposing of an ICBM – continued to attract attention. The demand for such a relatively cheap and simple means of putting small satellites into orbit was quite high around the world, especially in developing countries. Developers and designers had an idea: “Why don’t we sell decommissioned Topol ICBMs [NATO reporting name: SS-25 Sickle] to these countries?”.

These proposals carried a high risk of proliferation of ballistic technology. A nuclear bomb is not so difficult to produce today, and a number of states are in principle capable of doing so in the foreseeable future. But developing an effective and accurate means of delivering such a weapon is a much more advanced technology. Given the developing world’s poor record on technology protection and export controls, there is a non-zero chance that knowledge of how to build an ICBM could fall into the wrong hands. And that is a direct threat to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction technologies. It certainly does not make the world safer.

Some agencies managed to give positive feedback on the idea. However, it was 2016 and times were relatively calm, and the country’s leadership apparently did not want to anger major powers. Therefore, the MFA buried the idea by producing a harsh negative conclusion on it.

Since the introduction of sanctions against Russia in 2014, the idea of “symmetric” revenge against the Americans was in the air: “Let’s stop trading with them!”. Such suggestions were made by almost every second person, whether in the Foreign Ministry or in other departments. The first thing that came to mind was to freeze deliveries of RD-180/181 rocket engines.

The RD-180 engine was developed by NPO Energomash in the 1990s as a modification of the most powerful Soviet rocket engine, the RD-170. The main buyer of these engines was the United States, which used the RD-180 in its Atlas space rockets. They also bought the RD-181 for the first stage of the Antares space launch vehicle. In the 1990s and early 2000s, it was American orders that literally saved Energomash, Russia’s main rocket engine manufacturer, from bankruptcy and closure, as there was a catastrophic lack of budget funds to maintain the unique enterprise. The Americans bought engines by the dozen, bringing Energomash tangible profits in hard currency.

An analysis of the possible consequences of the engine export ban showed that the USA had built up a considerable reserve which would allow them to keep launching rockets for three or four years. During that time, they would undoubtedly accelerate the development of their own engines, which was already underway, and eventually the need for Russian RD-180/181 would disappear for good. Hence, Russia would be shooting itself in the foot, as it would lose money and, at the same time, would not be able to do any tangible harm to America.

Sergei Kislyak, Russia’s Ambassador to the US (2008-2017), regularly raised this issue in his reports. Reporting on yet another “unfriendly” move by the US, he suggested considering options for suspending or completely halting cooperation with America in the space area or, at least, stopping the sale of rocket engines. This went on for quite a while, until eventually Sergei Ryabkov, Deputy Foreign Minister (since 2008), scribbled a resolution on one of the telegrams: “A well-considered decision has been made – keep selling [rocket engines] while they sell!”.

This kind of common sense was also evident in matters of cooperation with Ukraine, despite the deterioration in relations. In 2014, for example, almost all shipments of industrial goods to that country began to be subject to a catch-all control procedure: exporters had to apply to the government’s Export Control Commission for permission to export products that could potentially be used for military purposes. Although gradually decreasing, there was still a large trade turnover between Russia and Ukraine at that time.4 Thousands of companies were closely linked by economic ties, while many Russian companies had contractors in Ukraine and vice versa.

From the very beginning of the 2014 Maidan Revolution, many in Russia voiced the following opinion: “Since we are now enemies with Kiev, let’s stop doing business with them altogether”.5 Those were the voices of people who were completely out of touch with reality, or who were simply looking for PR at any price. An abrupt end to trade relations would have brought a huge number of Russian companies to the brink of ruin. Ukraine was one of the main markets for many Russian products, so only the short-sighted people could dream of a complete break in economic relations.

However, at many interdepartmental meetings on controlling the export of certain types of products to Ukraine, participants often expressed more down-to-earth views. At that time, for example, a joint Russian-Ukrainian project manufactured the An-148 aircraft, which was also to be used for Russian military transport aviation needs. The aircraft was assembled in Russia, but a number of components were supplied from Ukraine. At closed meetings, experts argued that if Russia wanted to produce such aircraft, it would have to continue working with the Ukrainians.

Another example, even more telling, was the situation with the Motor Sich aircraft engine manufacturer based in Zaporizhzhya. This was the only factory in the post-Soviet space that produced turboshaft engines used in all Soviet and later Russian helicopters. After relations with Ukraine began to deteriorate, there was a risk that engine sales would cease, and the entire Russian helicopter forces and industry could be grounded in a short space of time. At the same time, Motor Sich’s products were predominantly aimed at Russia: it produced engines for Mil and Kamov helicopters, and without Russia the plant would not have had the lion’s share of its orders. Russia was afraid that Motor Sich would stop deliveries and cause great damage to the Russian aviation industry and air force capabilities, and Motor Sich was afraid that it would lose its main customer and the company would be on the verge of survival. Therefore, despite the fact that from the very beginning of the Maidan Revolution in Ukraine there were calls to stop any relations with the Russians, especially in the defence sector, Motor Sich continued working with Russian partners until very recently.6 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for its part, facilitated the rapid issuance of necessary permits.

However, this policy was not always followed. Following the Russian annexation of Crimea, Ukraine quickly severed trade relations between Mykolaiv-based Zorya-Mashproekt, the main manufacturer of gas turbine engines for ships, and Russian customers. As a result, the Russian Navy was left without engines, and their production had to be hastily set up at the Saturn engine plant in Russian Rybinsk.

At the same time, conspiracy theories and paranoid views, echoed by various echelons of the security services to demonstrate their “understanding” of the concerns of the top leadership, gradually spread throughout the state apparatus and began influencing decision-making.

One example is the export of samples of blood and other human tissues, which a number of Russian scientific institutes exported to American and British laboratories as part of multi-year joint projects. For a long time, the FSB tried to stop these contacts, openly fearing “the possible creation of genetic or ethnic weapons” against Russians.7 Before 2014, these anti-scientific conjectures were quite easily rejected, but against the background of the escalating confrontation with the West, the backward thinking in the FSB got a second wind and such cooperation was terminated in 2015.

Accusations against Ukraine of developing biological weapons such as “mutant mosquitoes” and the like became a proverbial parable. These accusations began appearing en masse after the start of the Russian full-scale aggression in 2022.8 However, they did not come out of nowhere: years of tendentious observations, by members of the Russian Security Council, of US cooperation with the CIS countries in the field of biology contributed to the growing paranoia about US intentions.

Even though the USSR had signed the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention in 1972, many Western countries suspected that research into the development of biological weapons had not ceased in the Soviet Union. It is known that the test site Aralsk-7 on the Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea operated until 1992, when it was officially closed by decree of President Boris Yeltsin and all equipment was dismantled.

Given the recent history of chemical weapons development in Russia,9 it is difficult to be certain that similar developments are not now underway in the biological field too. At the same time, the growing concern and anxiety of the Russian authorities, especially the special services, about biological developments in Western countries can also be interpreted as a fear that NATO military biologists will surpass their Russian counterparts in the field of biological warfare.

Moscow’s main fear is US penetration of Russia’s “underbelly”, i.e. invasion of Russia’s “primordial and exclusive” sphere of influence. In the 1990s, after the collapse of the USSR, the risks of losing control of Soviet weapons of mass destruction and related technologies increased dramatically. The US and other Western countries began to assist the new post-Soviet states in establishing national control systems, notably through the famous Nunn-Lugar programme.10 This led to the establishment of biological laboratories, including those with the highest level of protection, in a number of CIS countries. Such facilities were built in Ukraine, Georgia and Kazakhstan. According to Russian agencies, these laboratories are intended to develop special types of weapons, primarily directed against Russia and the Russian population, under the guise of medical-biological research.11

Sometimes, when reading documents and reference materials on this subject from various agencies,12 one had to scratch one’s head and check whether they had really come from the Defence Ministry or the FSB, and not from some conspiracy theory resource on the Internet. Those materials featured discussions about the development of genetic or ethnic weapons, as well as documents on joint research by American and Ukrainian or Kazakh universities on the spread of various pathogens in specific regions. As for the latter, those unclassified, publicly available scientific papers were presented at that time as obvious evidence of the development of banned biological weapons.

It was not easy to oppose the Americans and their laboratories in the CIS countries. Firstly, the states themselves did not object, at least not to the US helping them to build up their health care systems and strengthen their anti-epidemic and sanitary capacities. Russia was unwilling or unable to offer competitive projects, but for some reason expected Russian interests to be more important to the CIS countries than their own.

The Russian MFA came up with a “reliable” and “efficient” way to obstruct allegedly dangerous US biological activities in Russia’s “underbelly”. The idea was to conclude a bilateral intergovernmental memorandum of understanding on biological security with each CIS country. Such memoranda would commit the parties not to allow any third party to conduct biological activities on their territory and to cooperate in every way possible. It was the provision on the “third party”, i.e. the United States, that was the key to the document.

Thus, Russia offered its partners to stop any cooperation with other countries, especially those with developed biotechnologies. Those memoranda were an example of imposing an unequal partnership, in which the CIS states would have to sacrifice their interests in the field of economic development, specifically the development of scientific, industrial and technological relations with other states, just because Russia was scared that the Americans would supposedly use them to breed mutant mosquitoes capable of carrying diseases that would exclusively affect Russians or any other ethnic group living in Russia.

However, not all MFA officials were “hooked” on such arguments either in the biological weapons-related area or in general. For example, in a conversation with a colleague at the Russian Embassy in Kyiv in 2017, I heard a curious theory about the origins of the “Ukrainian crisis”:

Broadly speaking, the conflict between western and eastern parts of Ukraine is a struggle between the city and the countryside. The west has always been more rural, while the east has always been more industrial and therefore more urbanised. There are more people in the west who speak Ukrainian, while the east, because of its industrial development, was much more integrated into Russian society and the Russian-speaking space.

I also heard some curious impressions of Mikhail Zurabov’s work as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to Ukraine (2009-2016). Contrary to the negative public opinion about him in Russia, he turned out to be a very smart ambassador, according to some colleagues who had worked with him. “He is a mathematician and has done research on decision-making algorithms”, said one colleague, describing his impressions of Zurabov. Zurabov had studied Ukraine’s political life closely, and long before the Maidan Revolution, he had used some of his mathematical models to conclude that a social explosion in Ukraine and a turn towards the European Union were inevitable. He repeatedly wrote to the Centre on this subject. And a few months before Maidan, according to sources, not only did he write again to Moscow, but also travelled there to personally convince decision-makers of the need to change Russia’s course on Ukraine. But the ambassador’s advice fell on deaf ears: Moscow allegedly knew what was happening in Ukraine better than the people who lived and worked in Kyiv. Zurabov was laughed at and accused of alarmism and scaremongering. Naturally, his advice could not have been perceived otherwise against the background of the most positive reports from other agencies about how the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians loved Russia and President Viktor Yanukovych, and were wary of the West, the EU and NATO.

Zurabov was not a common ambassador: as a former minister and presidential adviser, he had access to high office – unlike the vast majority of other Russian ambassadors for whom a meeting with a deputy minister is the pinnacle of their administrative skills. However, even he failed to persuade the country’s leaders of the fallacy of their Ukraine policies. But even their very own negative experience in 2014, too, failed to convince them of anything.

The Russian leadership’s lack of a reasonable ideology to offer to society (the ideology of “we live large but you can have table scraps” could hardly find widespread support) led those involved in foreign policy to construct their own visions of the goals and objectives of Russian foreign policy in global terms. This sometimes gave birth to odd statements.

At the advanced training courses for senior diplomats held at the Diplomatic Academy, elderly professors, who still remembered the heyday of historical and dialectical materialism in the USSR, spoke of the decline of international diplomacy. The audience was told about the deterioration of international relations, the decreasing level of stability, and the emergence of new centres of power claiming an important role in solving major issues on the international agenda. In that difficult environment, Russia naturally defended its legitimate interests, advocated a multipolar world, and opposed forcing the international community to impose unilateral sanctions.

Discussing the nature of international relations, a very old professor said: “Do you know why international relations are in such a state today? Because the truth has gone out of them!”. And he continued: “There is no more truth in world politics, everything is based on selfishness and national interests. Russia must bring this truth back”.

At the time, in 2015, this speech made a depressing impression on our entire group. There were a few colleagues who diligently wrote down everything the professor said, but most of them just laughed and twisted a finger at a temple. Today, I fear, many would greet a speech on the lack of truth in international relations with loud and prolonged applause.

The second revelation came at the same course during a meeting with the Deputy Director of the Second CIS Department, who was responsible for Belarus. He was talking about the state of our relations with Minsk, which, according to him, were excellent. During the Q and A session, the audience asked if there were any scenarios in case of a repetition of the events of the Ukrainian Maidan in Belarus? What would we do in such a situation? The answer from the diplomat responsible for Belarus was direct and simple: “President Lukashenko is in power; we have excellent relations with him. Nothing will happen in Belarus”. “OK, but what if something were still to happen to such a good president? People are mortal, and above all, they can die suddenly. What then? What is Plan B?”.

As it turned out, there was no Plan B. There was only one plan – to support Lukashenko. That was the height of strategic planning for Russia’s closest ally, even though it was already 2015. A year earlier, Moscow’s other closest ally and protégé, President Viktor Yanukovych, in whom Russia had invested dozens of billions of US dollars, was overthrown, quite unexpectedly for the Russian leadership. It would seem that we should learn lessons and be prepared for similar things in the future. But no, we will continue to pursue a policy that has proved to be wrong.

This is where the characteristics of the worldview and world outlook of the Russian leadership – Putin and his entourage, whom all other Russian officials, including Lavrov, try to accommodate – are particularly evident. It is the conviction that everything in the world is organised exactly the same way as in Russia. Corruption is the same everywhere, everything is decided by the head of state or government, and no grassroots social activism can exist on its own but is only ever a cover-up for those in power. For example, the take on Lukashenko demonstrated by Deputy Director of the Second CIS Department is the view of one “eternal” dictator, convinced of his irreplaceability, on another dictator who, quite naturally, should also be “eternal”. In this paradigm, occasional failures are interpreted as the intervention of malign external forces, but in no case as proof that the approach itself is wrong.

At the same time, despite the search for malice and conspiracy everywhere, no practical work was done in the MFA to prevent such “conspiracies” and to work out contingency plans in case of unexpected changes. The conspiracy of the intelligence services encountered the perpetual apathy and inertia of the diplomats.

The crowning achievement of this inadequate view of the world order was the infamous “ultimatum” of 15 December 2021, entitled “Russian draft documents on legal security guarantees from the United States and NATO”.13

The ultimatum demanded that the United States refuse to accept the states of the former USSR into NATO or to establish military bases in these countries, to cease all military cooperation with them, and to rule out further eastward enlargement of the Alliance. Furthermore, it was proposed to withdraw all military forces and weaponry from the territories of NATO members who joined after 1997.14 The US also had to agree not to interfere in Russia’s “internal affairs, including refraining from supporting organisations, groups or individuals calling for an unconstitutional change of power, as well as from undertaking any actions aimed at changing the political or social system”.15

The latter was the main point. All the struggle with NATO and the West was not about the parameters of arms control or the security of Russian borders: Moscow was concerned about, and afraid of, only one thing: support for attempts of “unconstitutional change of power”. In the minds of the country’s leaders, no protest or dissent can emerge on its own: it is always instigated from abroad with Western money, there was no other interpretation.

In essence, it was a demand that the United States recognise Vladimir Putin’s personal sovereignty not only over Russia but also over the entire former Warsaw Bloc – apparently as a security measure, a kind of “sanitary cordon”. The magnitude of the idea and its absolute discrepancy with the reality could only raise questions about the mental adequacy of the author of the text. One had the feeling that the US had just lost a war to Russia and had completely capitulated.

The documents were sent to the MFA by the Presidential Administration,16 and no one in the Foreign Ministry, including Lavrov, even mentioned that the proposals should have been edited in some way so that they would not look so outrageous.

No progress was made at the Russian-US consultations in Geneva on 10 January 2022 because Moscow refused to discuss its ultimatum – “NATO should pack its things and go back to 1997”.17

Devising their “ingenious” moves, Russian strategists failed to remember that in 1997, the year to which they dreamed to return NATO to, there were more than 300,000 US troops in Europe, as opposed to a few thousand in 2021. Was Moscow planning to bring such a number of US troops back to Europe? And what about the other borders of 1997? Whose was Crimea then, for example?

Moscow typically thought only of what it needed, and the simple idea that it would be good to look at the situation through the eyes of its enemy, if only to see the vulnerabilities in their own constructions, simply did not occur to the Kremlin leadership.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 was naturally a turning point for the Russian MFA. The need to provide full foreign policy and diplomatic support for the aggression came to the fore. This is no longer a matter of common sense, let alone a critical approach to the instructions that the MFA receives. For example, after the Russian Ministry of Defence sent, in March-April 2022, materials on the alleged development of biological weapons in Ukraine – the materials were publicly available presentations of US-Ukrainian studies on the migration of birds and insects carrying infectious agents – Russian diplomats were forced to disseminate that nonsense with a straight face.18 Expressing doubts about the quality of the materials and “evidence” of biological weapons could have been perceived as disagreement with the president’s policy.

In the third year of the “Special Military Operation”, the Russian MFA is an inherent element of the Russian propaganda machine; it lacks any subjectivity and is perceived by the Kremlin as a purely technical secretariat. Key foreign policy decisions appear to be made – without any challenge – by President Putin himself. In this context, it does not matter what the staff of the Russian MFA really believe – whether they sincerely share the paranoid ideas of Putin and Nikolai Patrushev,19 or whether they cynically do what is required of them without thinking or revealing their true thoughts – they are not the ones making the decisions.

Endnotes

-

- Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (New York: Grove Press, 1987), pp. 12-13.

- “Resolution 1973 (2011). Adopted by the Security Council at its 6498th Meeting, on 17 March 2011”, United Nations, 17 March (2011), https://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?OpenAgent&DS=S/RES/1973(2011)&Lang=E.

- “Rezhim Kaddafi mozhet proderzhat’sya tri-chetyre mesyatsa”, Moskovskiy komsomolets, 23 March (2011), https://www.mk.ru/politics/2011/03/23/575076-rezhim-kaddafi-mozhet-proderzhatsya-trichetyire-mesyatsa.html.

- See, for example, “Torgovlya mezhdu Rossiey i Ukrainoy v 2013 g.”, Vneshnyaya Torgovlya Rossii, 1 March (2016), https://russian-trade.com/reports-and-reviews/2016-03/torgovlya-mezhdu-rossiey-i-ukrainoy-v-2013-g/; “Torgovlya mezhdu Rossiey i Ukrainoy v 2014 g.”, Vneshnyaya Torgovlya Rossii, 1 April (2016), https://russian-trade.com/reports-and-reviews/2016-04/torgovlya-mezhdu-rossiey-i-ukrainoy-v-2014-g/.

- Editor’s note: For stylistic purposes, in quotes from Russian sources, we hereafter use the Romanised Russian, rather than Ukrainian, versions of the names of Ukraine’s cities and regions.

- Editor’s note: This was a matter of great controversy in Ukraine that officially banned deliveries of Motor Sich products to Russia in spring 2014. In October 2022, Ukrainian security sources arrested Vyacheslav Bohuslaev, the former owner Motor Sich, on treason charges: Bohuslaev apparently collaborated with Russian occupation forces and, in particular, continued to provide Russia with Motor Sich products despite the ban, see “SBU zatrymala prezydenta promyslovogo giganta Motor Sich za pidozroyu u roboti na rf”, Sluzhba bezpeky Ukrainy, 23 October (2022), https://ssu.gov.ua/novyny/sbu-zatrymala-prezydenta-promyslovoho-hihanta-motor-sich-za-pidozroiu-u-roboti-na-rf. A few months before Bohuslaev’s arrest, in May 2022, Russia’s Defence Ministry claimed that Russian “high-precision long-range air- and sea-based missiles” allegedly destroyed production facilities of the Motor Sich plant in Zaporizhzhia, see “Brifing Minoborony Rossii”, Ministerstvo oborony Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 25 May (2022), https://function.mil.ru/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12422983@egNews.

- “Rossiya blyudet chelovecheskiy obrazets”, Kommersant, 30 May (2007), https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/769777. See also Mikhail Gelfand, “Torgovtsy strakhom”, Troitsky variant, 20 November (2018), https://www.trv-science.ru/2018/11/torgovcy-straxom/.

- “‘Razgrebaem avgievy konyushni’. Nikolay Patrushev – o spetsoperatsii na Ukraine”, Argumenty i fakty, 29 March (2022), https://aif.ru/politics/world/razgrebaem_avgievy_konyushni_nikolay_patrushev_o_specoperacii_na_ukraine.

- “Ya sam porazhalsya ‘Novichkom’”, Kommersant, 3 April (2021), https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4743678.

- See John M. Shields, William C. Potter (eds), Dismantling the Cold War: U.S. and NIS Perspectives on the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997).

- “Minoborony RF: v biolaboratoriyakh SShA na Ukraine izuchali peredayushchiesya cherez komarov virusy”, TASS, 16 June (2022), https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/14935641.

- “Response by the United States of America to the Request by the Russian Federation for a Consultative Meeting under Article V of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC)”, United Nations, 5 September (2022), https://documents.un.org/api/symbol/access?j=G2247929&t=pdf; “Military Biological Activities of the US and Ukraine on the Ukrainian Territory in Violation of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BТWC)”, United Nations, 12 December (2022), https://documents.un.org/api/symbol/access?j=G2261022&t=pdf.

- “Press Release on Russian Draft Documents on Legal Security Guarantees from the United States and NATO”, Ministerstvo inostrannykh del Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 17 December (2021), https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1790809/?lang=en.

- “Agreement on Measures to Ensure the Security of the Russian Federation and Member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization”, Ministerstvo inostrannykh del Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 17 December (2021), https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/rso/nato/1790803/?lang=en.

- “Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Security Guarantees”, Ministerstvo inostrannykh del Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 17 December (2021), https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/rso/nato/1790818/?lang=en.

- “‘My russkie i my ne mozhem oshibat’sya’. Kak diplomaty poteryali vliyanie na Putina i ne ostanovili voynu”, BBC News, 3 August (2023), https://www.bbc.com/russian/articles/cxrxlwr2q4ro.

- “Ryabkov zayavil, chto NATO nado sobirat’ manatki i otpravlyat’sya na rubezhi 1997 goda”, TASS, 9 January (2022), https://tass.ru/politika/13380415.

- “Questions to the United States Regarding Compliance with the Obligations under the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction (BTWC) in the Context of the Activities of Biological Laboratories in the Territory of Ukraine”, United Nations, 15 September (2022), https://documents.un.org/api/symbol/access?j=G2248922&t=pdf. Documents collected by Russia can also be found here: https://documents.unoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/WP2-annexes-for-website.pdf. See also “Gosudarstvennaya Duma utverdila itogovy doklad Parlamentskoy komissii po rassledovaniyu deyatel’nosti biolaboratoriy SShA na Ukraine”, Gosudarstvennaya Duma, 11 April (2023), http://duma.gov.ru/news/56830/.

- Editor’s note: On Patrushev see also Martin Kragh, Andreas Umland, “Ukrainophobic Imaginations of the Russian Siloviki: The Case of Nikolai Patrushev, 2014-2023”, Centre for Democratic Integrity, 6 October (2023), https://democratic-integrity.eu/ukrainophobic-imaginations-of-the-russian-siloviki/.