Putin’s Genocidal Quest for Symbolic Immortality

Anton Shekhovtsov

Director of the Centre for Democratic Integrity (Austria), visiting professor at the Department of International Relations at Central European University (Austria)

5 May 2025

This chapter is part of the volume Russia against Ukraine: Russian Political Mythology and the War on Ukrainian Identity, edited by Anton Shekhovtsov

Introduction

As Vladimir Putin started to strengthen his grip on power in the beginning of the 2000s, by taming political opposition, coercing independent voices into silence, and subduing defiant businessmen, a curious development started to take shape in the world of Russian speculative fiction. Fascination with interstellar wars, vampire sagas, and fantasy worlds of elves and orcs increasingly gave way to the intoxication with alternative history and, specifically, with its Russian subgenre of popadanstvo.1

This awkward Russian neologism is derived from the verb popadat’ which can be translated as “to find oneself (somewhere/somewhen)”. A typical popadanstvo novel is centred on a Russian protagonist (popadanets, singular, and popadantsy, plural) who is transferred to, or finds themselves in, a different time and/or space. The closest meaning of the phrases in English would be “accidental travel” for popadanstvo, and “accidental historical tourists” for popadantsy.

As a form of alternative history, popadanstvo is hardly new: as early as 1889, Mark Twain published a novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which is considered to be the first fiction work in this genre. Where the Russian subgenre stands in stark contrast to other forms of alternative history fiction, however, is in its preoccupation with protagonists using their adventures to benefit the Russian state.

Three historical periods are especially popular with Russian authors: Kyivan Rus, the Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union. Protagonists are transferred to those times or have their minds transferred into bodies of prominent people of those periods. Armed with historical knowledge, they help prevent tragic developments in Russian history or secure victories over Russia’s enemies. Thus, hordes of fictional Russian commandos, re-enactors, and even ordinary people travel to the Russian past on the pages of “accidental travel” novels to fight against Turkic nomadic invaders, Napoleon’s army, Third Reich, and other calamities. But sometimes, historical personalities are transferred to the future. For example, in one novel, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s agents travel to contemporary Russia to provide advice to Putin on how to defeat the West and internal enemies.

The surge of alternative history fiction in Russia can be seen as a psychological response to a profound crisis of Russian collective identity. This crisis was born from the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the grinding poverty of the 1990s, and the bitter humiliation of military defeat in the First Chechen War. In weaving tales of personal and national triumph, the fiction industry did more than offer escapism – it tapped into, and perhaps even deepened, a pervasive sense of collective inferiority and the ache of historical disempowerment.

In his writings on myth and ritual, Mircea Eliade argued that by immersing themselves in adventure literature and identifying with fictional heroes on transformative quests, young readers experienced a secular form of rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood.2 Likewise, popadanstvo literature appears to offer Russian readers with illusory compensation for a wounded national self-concept, nurturing patterns of escapism and externalised blame, and subtly transforming its audience into popadantsy themselves.

One infamous real-world popadanets is Igor Girkin (“Strelkov”), a retired officer of Russia’s Federal Security Service (or FSB), who played a key role in the 2014 Russian invasion of eastern Ukraine. A devoted fan of historical literature, Girkin was deeply involved in military re-enactments prior to the invasion. He had a particular fascination with the Russian Civil War, often donning a White Guard officer’s uniform to “act out long-ago battles” against the Bolsheviks – though occasionally, he switched sides – alongside a circle of like-minded enthusiasts.

For Girkin, the Russian invasion of Ukraine became a real-life portal – a chance to find himself in the “future” as “a White Guard officer”, fighting to help contemporary Russia restore the empire lost when the Bolsheviks seized power. By taking part in the 2014 war against Ukraine, he attempted to reverse what he saw as a national catastrophe that had befallen his fatherland in “his” 1917, a past he felt deeply connected to through historical re-enactment.

Although different from Girkin in stature and influence, Putin too can be seen, in a sense, as a popadanets. For Girkin, the pivotal rupture in need of repair was the collapse of the Russian Empire. For Putin, there are two overlapping wounds in the fabric of history. The first is the West’s victory in the Cold War – a triumph that shattered the socialist bloc and hastened the Soviet Union’s fall. The second is Ukraine’s assertion of its own national selfhood, its departure from the gravitational pull of the so-called “Russian world”.

Putin’s war – both against the West more broadly and Ukraine specifically – thus emerges as an attempt to “correct” history, to forge a present in which these ruptures no longer define the historical landscape. In other words, it is a war of “alternative history” – a war to undo the West’s triumph and to erase Ukraine as a nation distinct from Russia.

“Moscow is silent”

A wave of revolutions swept across the Eastern Bloc in 1989. Encouraged by democratic breakthroughs in Poland and Hungary, mass protests in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) gained momentum in autumn that year, demanding political reform and freedom of movement. On 9 November, following weeks of unrest, East German authorities unexpectedly announced that citizens would be allowed to travel freely to West Germany and West Berlin. Thousands gathered at the Berlin Wall from both sides, crossing through checkpoints or climbing over it – marking the beginning of its dismantling and the symbolic collapse of the Iron Curtain.

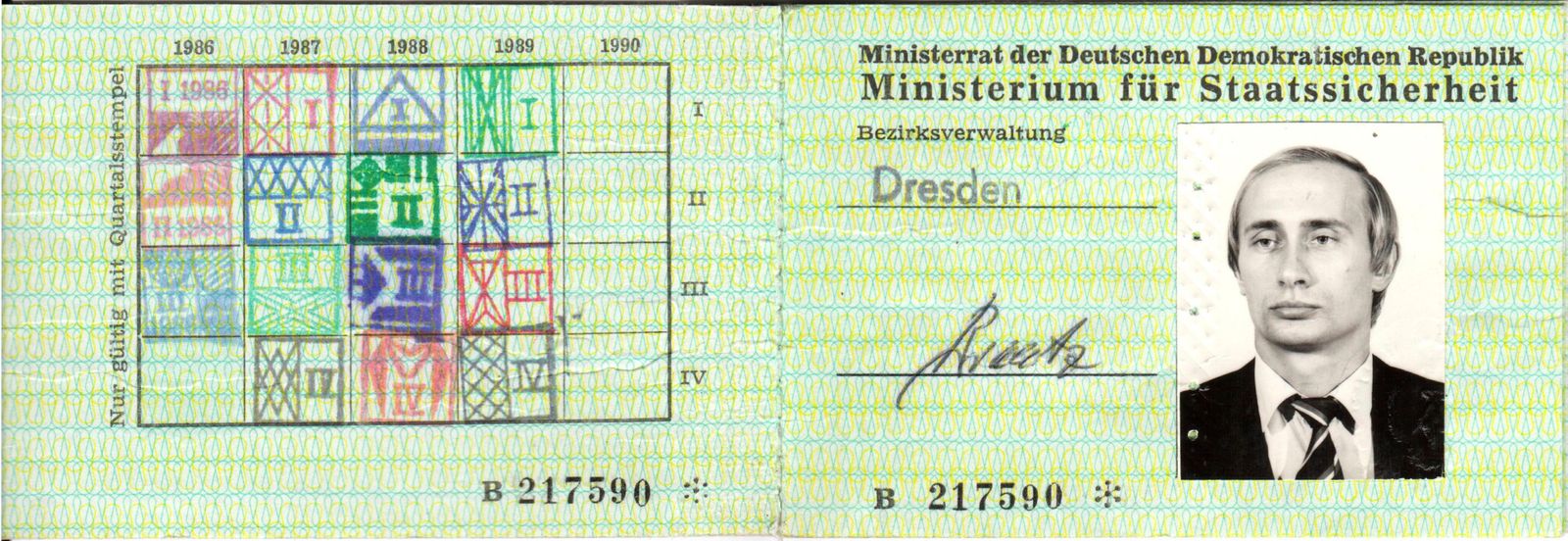

At the time, Vladimir Putin, then a KGB officer in his late 30s, was stationed in Dresden, East Germany. Operating out of the KGB residency located in a villa at Angelikastrasse 4, he apparently managed a network of agents in West Germany from 1985 onward.3 Amid mounting political pressure in East Germany – and following the storming of the Stasi district headquarters in Dresden by pro-democracy demonstrators on 5 December 1989 – the KGB residency in the city was dissolved in February 1990. The same month, Vladimir Putin returned to the Soviet Union.

A decade later, Putin was on the verge of being elected president of Russia for the first time. His campaign leaned heavily on so-called political technologists – specialists who manage and manipulate political processes through strategic communication, media control, propaganda, and electoral tactics to shape public opinion.4 To bolster his image, these technologists began constructing a heroic myth around the final chapter of Putin’s KGB service in Dresden. They built on a historical detail: after protestors stormed the Stasi headquarters in Dresden, a small group of 15-20 German pro-democracy activists made their way to the nearby KGB residency, located just minutes away.

In the mythologised version, this small group became an unruly “mob” of aggressive, predominantly young men determined to break into the KGB villa. Putin, according to the narrative, called the Soviet military command in Dresden to request reinforcements to protect the building and its secrets. The command responded that it could take no action without Moscow’s authorisation and promised to inquire. When Putin telephoned back, they said they had relayed the request but Moscow was silent. In other words, neither the Soviet military command in Dresden nor the central authorities in Moscow were willing, or able, to act.

At that moment, the narrative took on its cinematic tone. Putin stepped outside to confront the crowd. He calmly told them that the villa belonged to the Soviet Army and that they were not permitted to enter. He warned that Soviet soldiers inside had orders to open fire if anyone attempted to breach the premises. Then he turned and walked back into the building. Confused and apparently unnerved, the crowd dispersed.5

This narrative about Putin was built on his earlier manufactured image of a modern Russian manifestation of Vsevolod Vladimirov – the fictional Soviet spy who, under the alias Max Otto von Stierlitz, infiltrated Nazi Germany as a high-ranking SS officer during the Second World War. Originally invented by Soviet writer Yulian Semyonov as a literary character in the 1960s, Stierlitz became one of the most beloved cult figures in Soviet and, later, Russian popular culture thanks to the 1973 Soviet TV series Seventeen Moments of Spring.

Semyonov’s novel, which inspired the TV series, was commissioned by the KGB chief Yuri Andropov. Both the book and its TV adaptation were part of a propaganda effort to glorify Soviet spies abroad, reshape the KGB’s repressive image, and attract young recruits to a more heroic vision of the secret service.6 The TV series inspired many a young Soviet man to join the KGB’s foreign intelligence service, and Putin was no exception.7 A fan of Stierlitz and other Semyonov’s novels, he joined the KGB in 1975, just two years after the series aired.

In the early 1990s, while Putin was working as an adviser in the St Petersburg mayor’s office following his return from Dresden, a local director made a short documentary about him. In that film, Putin publicly acknowledged, for the first time, his past as a KGB foreign operative. Seizing on this, the director suggested he re-enact a scene from Seventeen Moments of Spring.8

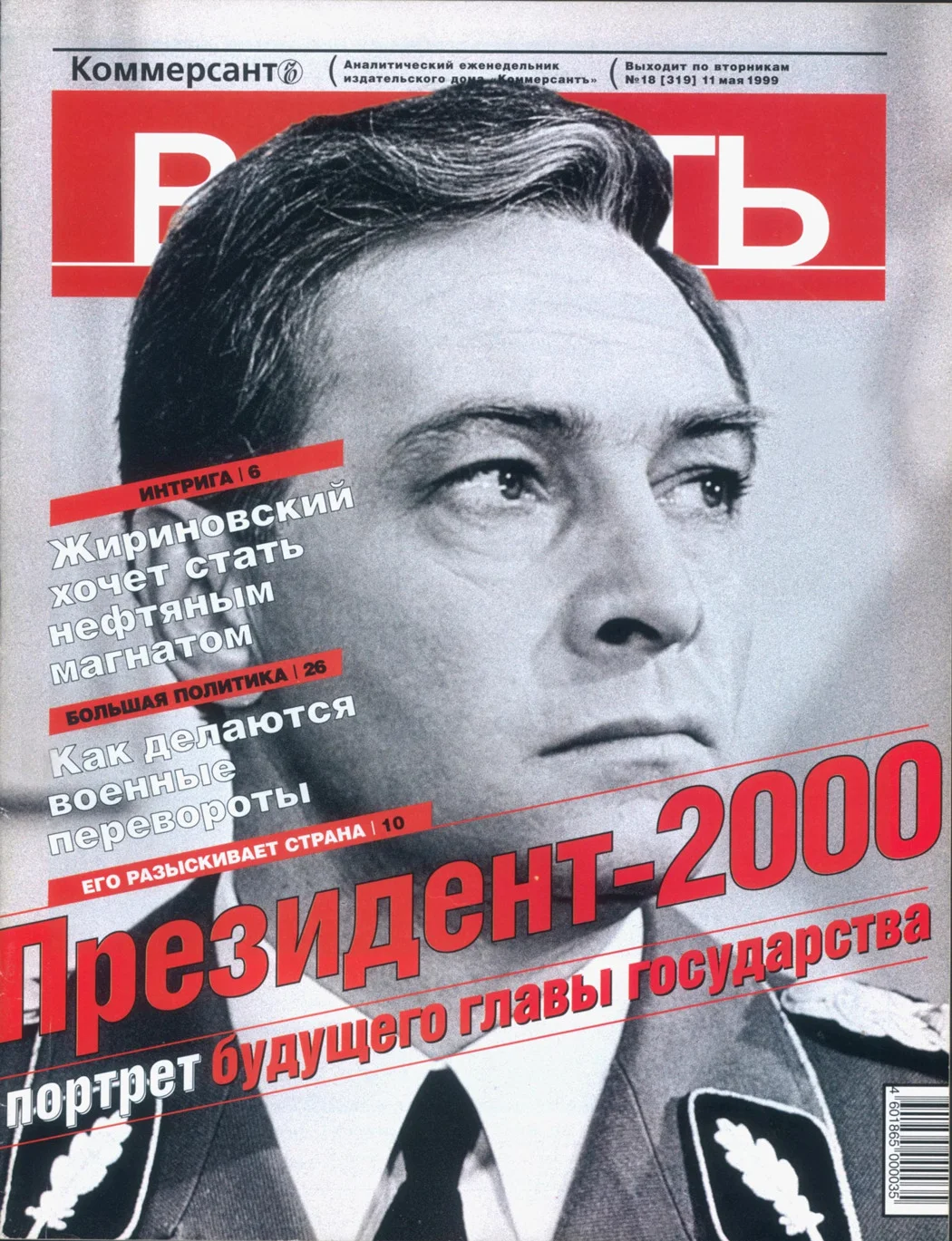

Putin’s early image as a modern-day Stierlitz, though not widely recognised by the public during the 1990s, proved highly useful to the political technologists preparing his presidential campaign in 1999-2000. Humorous public opinion polls at the time showed that Stierlitz ranked among Russians’ favourite fictional candidates for president. One cover of the influential Russian magazine Kommersant even featured, in May 1999, the Soviet TV image of Stierlitz with the caption: “President-2000: a portrait of the future head of state”.9

Putin’s political technologists ensured that, if anyone missed the connection between Putin and Stierlitz, “articles in the press reminded them of the resemblance and helped create the association”.10 By the time of the 2000 presidential election, Putin’s consultants had reinforced the Stierlitz reference by adding the narrative of the Dresden standoff, crafting a seemingly solid and persuasive heroic image: a fearless former spy, capable of calming angry crowds yet unflinching when toughness was required.

There is no independent evidence to verify Putin’s account of the events in Dresden on 5 December 1989,11 but it remains plausible that he witnessed the swelling crowds of German pro-democracy demonstrators in the autumn and early winter of that year. Moreover, the ideas and messages embedded in the narrative about the standoff by the KGB residency may offer more insight into Putin’s political thinking than the facts themselves.

“Wir sind das Volk!” – “We are the people!” – was the defining slogan of the democratic Peaceful Revolution in East Germany that Putin witnessed firsthand. In 1989, it was ordinary people who demanded democratic reforms, and it was ordinary Germans who ultimately dismantled the authoritarian GDR. “Wir sind das Volk!” was the slogan of assertion of popular democratic sovereignty.

For a KGB officer representing the interests of the Soviet Union, the slogan and the events behind it – embodying the triumph of the small over the mighty – must have been profoundly unsettling on multiple levels.

The people’s victory over the Party was, above all, a humiliation. The KGB’s central role at home was to maintain repressive control over the population. This role was executed even more ruthlessly by its East German counterpart, the Stasi – infamous for the sheer intensity of its domestic surveillance.12 These agencies existed to ensure that people could never claim freedom or sovereignty.

Though the regimes of the Soviet Union, the GDR, and other socialist states claimed to speak for the people, in reality they served only themselves – the Party and the security apparatus. This was the ultimate arrogance of the corrupt socialist elites: to pretend to voice the will of the people while using every instrument of coercion, up to and including physical elimination, to crush it. The Party was the supreme authority; the role of the people was to obey. And it was the secret police that ensured they did.

What happened in Dresden and across the GDR in 1989 was a blunt repudiation of the elitist dogma Putin had been trained to enforce. It was the first victorious “colour revolution” he saw up close – and the first of many he would come to loathe, both for what they reminded him of and for popular democratic sovereignty they stood for.

No less humiliating was the sense of helplessness of the Soviet Union in the face of the 1989 events in East Germany, a country the Soviets regarded as their satellite. Moscow was silent – it could not respond the way that Putin and his fellow secret agents hoped it would, as it did during the East German uprising of 1953, or the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, or the Prague Spring of 1968. As the Soviet Union failed to reinforce its domination over satellites, it was the end of the state for Putin. As he would later recollect, he “had the feeling then that the country was no more. It became clear the Union was sick. It was a deadly, incurable disease called paralysis. A paralysis of power”.13

The Peaceful Revolution in the GDR in 1989, and the broader collapse of Soviet domination, were not merely a geopolitical shock but also a deeply personal and existential one for Putin. Even if his career prospects within the system of elitist privilege remained relatively secure, for a KGB officer trained to subordinate himself entirely to the state – to live for and through it – the state’s deadly paralysis marked a profound identity crisis.

It was not just the Soviet system that was unravelling; so was the very foundation of Putin’s sense of self. In 2005, he described the collapse of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century, and urged the Russian elite to “acknowledge” this loss.14 And while many did share his view of the collapse as a national tragedy, for Putin it was, above all, a deeply personal trauma.

It is natural for humans – as the species uniquely capable of understanding the inevitability of death – to seek ways of reconciling the instinct for self-preservation with the knowledge of mortality by identifying with entities greater and more enduring than the individual self: family, communities of faith, nation, state. These collective identities offer a sense of continuity that transcends a single human life, by shielding “ourselves from the devastating awareness of our underlying helplessness and the terror of our inevitable death”.15

We imagine that we will not truly die when our time comes if we believe our soul will continue to live after departing its mortal sheath. Or we imagine that, if we leave descendants behind, we will live on through them – just as our ancestors live on through us. Alternatively, or in addition, we may envision ourselves living on through a collective which we conceive as our nation or our state: by contributing to its prosperity and grandeur, we gain the hope of being included in its cultural memory, and, thus, of securing a lasting place in its story.16

What results from these beliefs is that the more we trust these cultural strategies to evade death, the deeper we internalise them, the less tolerant we become of those perceived as threatening the collective identities with which we associate ourselves.17 The instinct to protect one’s offspring is common across much of the animal kingdom, and in humans it is typically amplified by culture. Defence of one’s nation, religion, or state is predominantly cultural, but is often no less fierce than in the case of protecting one’s next generation, where evolutionary instincts are reinforced by cultural conventions. The reason for this is that we do not defend an abstract identity, national or religious – rather, we defend our pathway to symbolic immortality.

The perceived deadly sickness of the Soviet Union, followed by its dissolution, was not only a geopolitical rupture but also a blow to Putin’s psychological armour that had shielded him from existential dread by promising survival through the Soviet state.

The exact opposite of symbolic immortality is oblivion. Three decades after the Soviet collapse, Putin would draw a direct parallel between the paralysis of power and oblivion, thus indirectly associating the survival of the state with symbolic immortality: “In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union grew weaker and subsequently broke apart. That experience […] has shown us that the paralysis of power and will is the first step towards complete degradation and oblivion”.18

However, the Soviet Union did not simply “grow weaker” and “break apart”. The blow to Putin’s psychological armour came from the West: it was the West that emerged victorious from the Cold War, which ended with the fall of the Soviet Union. Yet the West, while the primary source of this geopolitical trauma, was not the only one. It was also the ordinary people and their pursuit of popular democratic sovereignty who dismantled and humiliated the foundations of the repressive state – and, in doing so, shattered the very structure that had held that psychological armour together.

The underlying logic of popadanstvo is that once a specific historical turning point is identified as detrimental to Russia – whether as the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union – a protagonist can travel back in time to change it and thereby “correct” the present. Over time, Putin appeared to have gradually embraced the idea that alternative history could be transformed into political reality.

His-story of Ukraine

Ukrainian human rights activist Maksym Butkevych volunteered to join the Armed Forces as a lieutenant immediately after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In June 2022, he was captured by Russian forces along with several soldiers from his platoon. As the Russians sought to break their spirit and will, both physical and psychological torture became a routine.

The first time Butkevych was severely beaten in captivity was over Ukraine’s history. He and his fellow soldiers were forced to kneel before a Russian officer. The officer took out his smartphone and started reading aloud from Putin’s speech announcing the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 – focusing on the parts concerning Ukrainian history. The prisoners were ordered to repeat each line word for word. Every time someone stumbled, hesitated, or lost their place, the officer struck Butkevych hard with a wooden stick. By the end of the torture – and long after – Putin’s “history of Ukraine” was etched into Butkevych’s tormented body.19

Much of Putin’s speech was devoted to his multiple grievances about the West and its alleged political, military, and cultural threat to Russia. Western powers, he claimed, ignored Russia’s security concerns. The West is hypocritical and morally bankrupt. It forcefully imposes corrosive values on Russia – values that, according to Putin, run contrary to Russian traditions and weaken Russian society.

Yet the speech also featured Putin’s “historical” explorations of Ukraine – narratives that would later be used as part of the torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Putin denied Ukraine’s sovereignty by portraying it as historically and culturally inseparable from Russia. The idea of a sovereign Ukraine is framed as a Nazi endeavour and, therefore, as dangerous and illegitimate. Ukraine is depicted as a passive object manipulated by the West with the aim of weakening Russia.

Putin’s narratives on Ukraine built on his earlier pseudo-historical article, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, published about half a year before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and widely seen as the “theoretical” preparation for it.20

The article proceeded from the premise that Ukrainians are, in fact, Little Russians (malorosy), who – together with Great Russians (velikorossy) and White Russians (belorusy) – comprise the single, large Russian nation. The Ukrainian national project, which rejects the “Little Russians” construct, is thus portrayed as illegitimate, artificial, and the product of foreign interference. The article concludes that Russia has a fraternal duty to preserve “the unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, casting Ukrainian independence as both a historical error and a geopolitical threat.

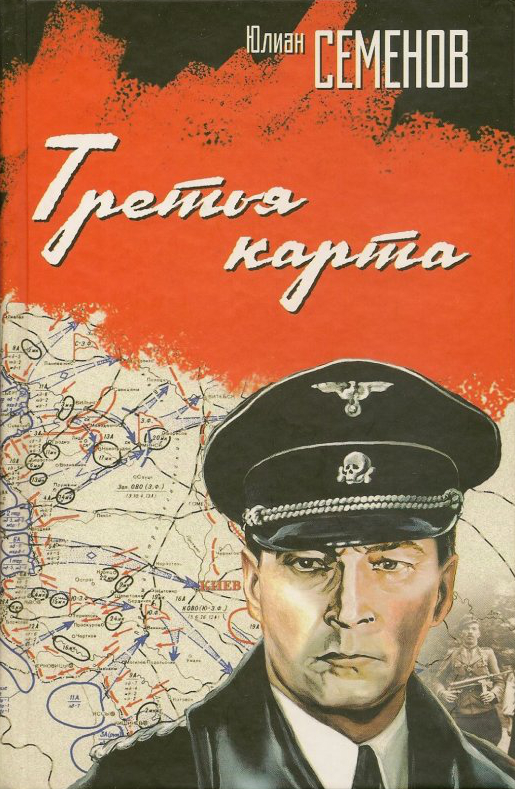

Putin’s “history” of Ukraine is less his own creation than an echo of older, inherited myths. In 1975, the year Putin joined the KGB, Yulian Semyonov wrote yet another novel about Stierlitz, A Third Card, this time placing significant focus on the Ukrainian national-liberation movement – a movement the novel sought to discredit.21

The timing of the publication was anything but accidental. In 1975, nearly all European countries – along with the Soviet Union, the United States, and Canada – signed the Helsinki Final Act, a non-binding political agreement aimed at improving relations between East and West during the Cold War.

The Final Act was the outcome of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, and covered security, economic cooperation, and human rights. In particular, the document argued that all peoples have the enduring right to freely determine their internal and external political status, and are free to pursue their political, economic, social, and cultural development as they see fit. Moreover, the signatories agreed to “respect the equal rights of peoples and their right to self-determination”.22

In several Soviet republics, in particular in Ukraine, Baltic republics, Georgia, and Armenia, the Final Act energised national-liberation and human rights movements that increasingly demanded greater national cultural rights, autonomy, and even independence. The formation, in 1976, of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, was a notable example of the developments. The Group directly cited the Final Act in its attempt to press the Soviet authorities for compliance with human rights and national self-determination. Hardly surprising, the Soviet regime viewed such movements as a threat and unleashed repressions against them.

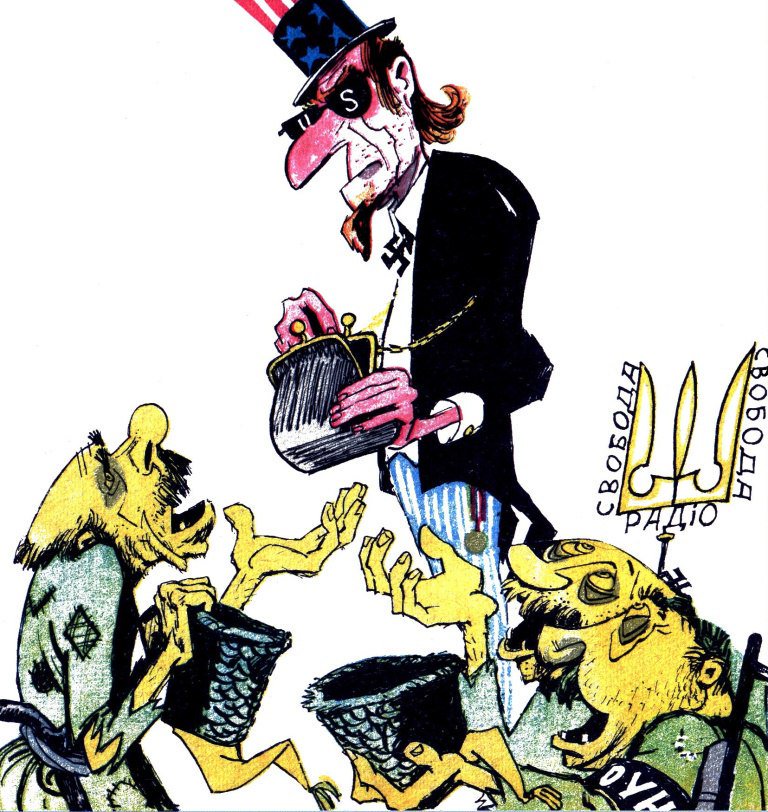

Repressions against members of national-liberation movements – Ukrainian in particular – ranged from “soft” measures such as surveillance, harassment, censorship, and forced emigration, to more severe tactics, including physical violence, long-term imprisonment in labour camps, and punitive psychiatric hospitalisation. There was also a more subtle form of repression: cultural warfare. The novel A Third Card, written by KGB collaborator Yulian Semyonov and aiming to demonise the Ukrainian national-liberation movement through fiction, exemplified this approach.

Like all other Semyonov’s works centred on Stierlitz, A Third Card blends elements of historical reconstruction, spy thriller, and alternative history. The novel transports the reader to 1941 – a key turning point in Soviet history – when Nazi Germany launched its invasion of the USSR. Moscow’s agent, Stierlitz, is tasked with destabilising the enemy from within by exploiting tensions between the SS and the Wehrmacht, and using Ukrainian nationalists collaborating with the Nazis, namely the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) led by Stepan Bandera, to further inflame the divisions within the fascist establishment.

The novel binds the very idea of a sovereign Ukraine, independent of the Soviet Union, almost exclusively to Bandera and his followers (Banderites), portraying the idea of Ukraine’s independence as a criminal enterprise instrumentalised by the Third Reich. In doing so, it strips Ukrainians of both dignity and historical agency. The Abwehr “promises” the OUN an independent Ukrainian state, but among themselves, German officers admit that Ukrainian nationalism is nothing more than a “paper handkerchief” – to be used and discarded once it has served its purpose in the war against the USSR.

In this narrative, the idea of the Ukrainian national project becomes an expendable and ultimately redundant “third card” in the geopolitical games of greater powers. Without the Soviet Union, Ukraine is a territory without a future – effectively a colonial void, to be shaped and occupied by stronger forces. Ukrainians themselves are portrayed as incapable of building or sustaining an independent state.

But the novel also had a twist. A Third Card was Semyonov’s eighth novel featuring Stierlitz, but it was the first to reveal – hardly by accident – that the Soviet spy Vsevolod Vladimirov, who operated under the alias Stierlitz, had both Russian and Ukrainian roots. His father was Russian, while his mother was Ukrainian – the daughter of a “Ukrainian revolutionary” exiled to Transbaikalia by the Russian tsarist regime for his political activities. This detail implied that Vladimirov’s mother had an ideologically correct biography: in Soviet terminology, a “Ukrainian revolutionary” was understood to be part of the progressive Ukrainian forces whose struggle for socialism was seen as aligned with, and part of, the broader revolutionary cause shared with Russians.

Vladimirov’s family background did not, however, make him equally Russian and Ukrainian. Semyonov’s “revelation” simply meant that Vladimirov’s biographical Ukrainian-ness was just a stream flowing into the river of Russian-ness. Vladimirov/Stierlitz embodied the “historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians” as understood through the lens of the Russian colonial paradigm.

Thus, Semyonov’s novel A Third Card presented two very different types of Ukrainians. One type comprised criminal Banderites, manipulated by anti-Russian forces into imagining the creation of an independent Ukrainian state as a means to undermine the Soviet Union. The other type consisted of Ukrainians whose Ukrainian-ness was subordinated to Russian ethnocultural identity and integrated into the “Great Russian” nation. The first type was dehumanised through association with fascism; the second was humanised through its relationship, albeit unequal, to Russian ethnicity. It was Ukrainians of this second type – fully integrated into Russian culture, with their Ukrainian-ness reduced to family names or a slight accent – whom Putin saw around him in the KGB, and who, indeed, differed little from their ethnically Russian colleagues.

It is easy to envision that A Third Card had a direct impact on how Putin, then a 25-year-old KGB recruit, came to perceive the Ukrainian national project. Semyonov’s novels were immensely popular in the Soviet Union – Stierlitz was a Soviet “James Bond” – and Putin himself admitted that he was fond of Soviet spy thrillers in his youth.23

Even if this notion may seem far-fetched, it is worth remembering that Semyonov was a KGB collaborator, and the political themes in A Third Card were not merely random fiction, but reflected the KGB’s prevailing views on the “Ukrainian question” at the very time Putin began his career in the agency. There is little doubt that he internalised the KGB’s stance on the Ukrainian national project through both his service and the literary products of Soviet cultural propaganda.

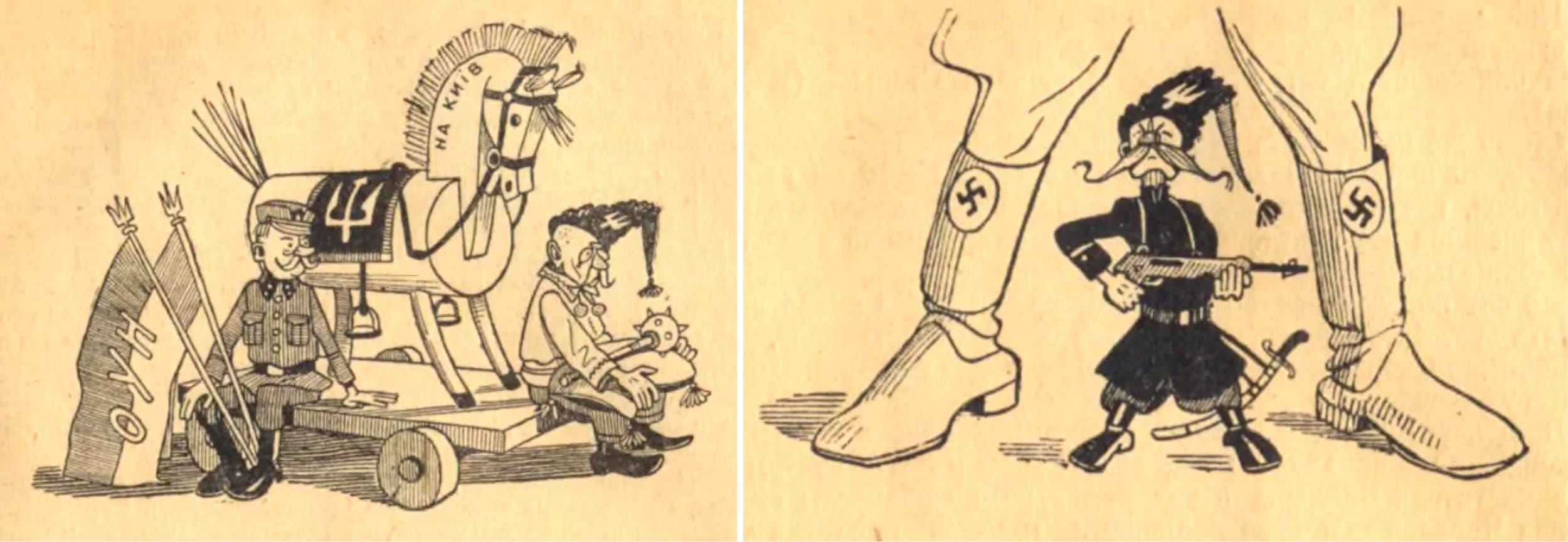

Moreover, Semyonov’s distinction between two social types of Ukrainians was neither his own invention nor that of the KGB. By the time he was writing, these stereotypes had long been established. Mykola Riabchuk traces their origins to the 18th century: on one hand, the “Little Russians” – “educated, loyal and basically integrated into the imperial culture”; on the other, the khokhly – “illiterate local peasants […] with a crude but picturesque aboriginal culture and a strange dialect”.24

The rise of nationalisms across Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe at the end of the 19th century, and the collapse of European empires in the early 20th century, gave momentum to the Ukrainian national-liberation movement, which was ideologically diverse, ranging from the far left, through the centre, to the far right. However, in the Russian colonial typology of Ukrainians, the figure of the “illiterate local peasant” – who, under the malign sway of anti-Soviet foreign powers, dared to dream of an independent Ukrainian state – was crudely recast as the criminal, fascist Banderite. The stereotypical “good Little Russians”, however, remained unchanged: they were those who accepted the primacy of “Great Russian” culture and were essentially regarded as part of “the single, large Russian nation”.

Ironically, Ukraine became independent in 1991 not through the nation-building efforts of the “Banderites”, but as a result of Moscow’s “paralysis of power”, which led to the fall of the Soviet Union. However, in the early post-Soviet years, Ukraine’s sovereignty stirred little concern in the Kremlin. As the country struggled through the collapse of the planned economy, hyperinflation, flawed privatisation, energy dependence, and population decline – all exacerbated by pervasive corruption – it remained firmly within Russia’s sphere of influence, with sovereignty more symbolic than substantive. For Moscow, this seemed to confirm a long-standing belief that khokhly were incapable of sustaining a truly independent Ukrainian state. And as long as Moscow-friendly “Little Russians” held power in Kyiv, the Kremlin was content to tolerate the status quo.

Yet as Ukrainian civil society matured, a series of intense popular protests increasingly challenged the rule of “Little Russians” in Ukraine, culminating in the 2014 national-liberation revolution that toppled the regime of pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. For Putin, this was a sinister echo from the past – a replay of the traumatic events he had witnessed in Dresden: a popular movement asserting democratic sovereignty by rejecting the rule of Russia’s puppets in a country Moscow believed to be a satellite state. “Ukraine is Europe!” – the slogan popular during the 2014 revolution – was the Ukrainian version of “Wir sind das Volk!”. The revolutionary movement spoke on behalf of the people of Ukraine and made a clear geopolitical choice: away from Moscow, and towards a united Europe.

However, the 2014 revolution in Ukraine was, for Putin, even more threatening than a replay of the Dresden events. Unlike in the GDR in 1989-1990, it was not merely ordinary citizens who challenged Russia’s political and cultural dominance in the region – it was nationally conscious Ukrainians, representatives of that dangerous type in the Russian imagination, whom the Kremlin immediately identified as fascists manipulated by the West to harm Russia.

This configuration added a new dimension to the blow to Putin’s sense of symbolic immortality, which was centred on survival through the state: Ukraine’s national self-determination. He came to see the very existence of the Ukrainian nation – which clove asunder the “Great Russian” state and, with it, the psychological armour shielding him from existential dread – as yet another rupture that could be repaired.

Unlike in Dresden in 1989, Putin made sure that Moscow would remain silent no longer. The war against Ukraine began.

“A fascist coup!”

Legend has it that when Stalin’s executioners prepared to shoot Grigoriy Zinoviev – a prominent Bolshevik revolutionary and close ally of Lenin who later fell out of favour with Stalin – he shouted that his execution was “a fascist coup”.25 Zinoviev’s life and death were paradoxical: he helped build the Soviet dictatorship, only to be destroyed by the very system he helped create. Equally paradoxical were the political consequences of his use of the term “fascism”, whose interpretation and manipulation may have contributed to many triumphs of inhumanity.

It was Zinoviev, then the chair of the Communist International, who introduced, in 1923, the concept “social fascism” to smear and undermine the Social Democratic Party of Germany as “nothing else than a fraction of German fascists under a socialist mask”.26 The adoption of the concept of “social fascism” by the German communists deepened hostilities between them and the Social Democrats. These hostilities eventually fractured the German left-wing forces and thereby paved the way for Hitler’s rise to power in the early 1930s.27

And it was Zinoviev who, while in exile in 1933, produced a peculiar translation of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. One peculiarity was that Zinoviev omitted sections dealing with Hitler’s autobiographical reflections and discussions of Nazi Party-building. The other was significantly more consequential: Zinoviev manipulatively overemphasised Hitler’s anti-Communist and anti-Soviet positions, portraying fascism primarily as a geopolitical threat to the USSR, while downplaying its broader ideological and racist dangers.28 Zinoviev’s Russian version of Mein Kampf was published as a limited edition “for official use” by the Soviet Communist Party elite and therefore had a direct impact on how the Soviet leadership – including Joseph Stalin – viewed fascism.

Officially and academically, Soviet leaders largely adhered to the Marxist interpretation of fascism as “an open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, the most chauvinistic, the most imperialistic elements of finance capital”.29 However, more casually – and especially after the Third Reich’s invasion of the Soviet Union – fascism came to be seen first and foremost as “anti-Sovietism”.

On a deeper symbolic level, the Nazi invasion of the USSR – which the Soviets referred to as “the Great Patriotic War” – was not perceived as a class war, as the Marxist definition of fascism would suggest. Instead, it became a “sacred war”,30 not against the Soviet system, but against the Soviet people, thus framing fascism as a threat to the nation, rather than to the class-based social structure.

After the Second World War, references to the “sacred” struggle against fascism in the Soviet Union took on clear aspects of symbolic immortality, often intertwined with Soviet nationalism. Phrases such as “the immortal feat of the Soviet people”, “eternal glory to the heroes”, “your name is unknown, your deed is immortal”, and “heroes never die” became integral to the Soviet politics of memory surrounding the “Great Patriotic War”.31 These expressions became indispensable, quasi-religious clichés used in state ceremonies, popular culture, journalism, education literature, and beyond.

These concepts and sentiments did not disappear from Russian public discourse after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, but their post-Soviet reproduction was transformed: “Soviet” was often either directly replaced by “Russian”, or the two terms coexisted in the Russian politics of memory – in both cases, collapsing the meaning of “Soviet” into “Russian”. The replacement of “the immortal feat of the Soviet people” with “the immortal feat of the Russian people” came to appear natural.

The Soviet-era framing of fascism as an ideology targeting the Soviet people, combined with the post-Soviet blurring of the line between “Soviet” and “Russian”, has organically led to the reimagining of fascism as an ideology directed specifically against the Russian nation. Moreover, the fight against fascism – now narrowly interpreted as anti-Russian ideology or practice – has acquired sacred characteristics, promising symbolic immortality to its combatants, just as “Soviet heroes” were immortalised with the claim that they would “never die”.

Two major political and cultural consequences have flowed from these metamorphoses, especially since Putin came to power and set Russia on an increasingly anti-Western course.

The first is that the Kremlin – along with the agents of its influence – now feels entitled to brand any political development perceived as hostile to Russia or the Russian people as “fascism” or “Nazism”. In the case of Ukraine, this has reinforced the Russian leadership’s portrayal of nationally conscious Ukrainians striving for genuine political independence as inherently anti-Russian – a framing that culminated in the depiction of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution as a “neo-Nazi coup d’état”, necessarily manipulated by the West.32 This, in turn, allowed Putin to frame the war against the Ukrainian nation as an operation of “denazification” – a term conveniently unpacked by one pro-Kremlin political technologist as the straightforward de-Ukrainisation of the territory of modern Ukraine.33

The second consequence is that the “denazification” of Ukraine – essentially a coded way of describing the destruction of a Ukrainian nation independent of Russia – has been cast as a sacred mission, promising symbolic immortality to all those involved in carrying it out. For Putin, in this sense, the elimination of Ukraine represents a way to fortify Russia – and, by extension, to reinforce the illusion of his own permanence.

The twisted logic behind this is rooted, in part, in the belief that a truly sovereign Ukrainian nation is an instrument of the West’s centuries-old “hybrid war” against Russia. By this reasoning, the destruction of the Ukrainian national project neutralises that instrument and delivers a retaliatory blow to the West without confronting it directly.

The erasure of Ukrainian identity thus becomes both an end in itself – an “immortal feat” – and a means to an end: retribution for the West’s Cold War victory over the Soviet Union, which, until its collapse, had shielded Putin from existential dread. One way or another, the eliminationist war against Ukraine became a pathway – direct or indirect – to his own immortality.

The architecture of a crime

An acquaintance of Vyacheslav Volodin, chair of the lower house of the Russian parliament, described him as “not the most intellectual person”, but someone who “is able to sense quite a lot – not with his brain but with his spine. A lot of his moves are made instinctually – he follows his nose and he knows which way the wind is blowing”.34

It was exactly Volodin’s gut feeling that led one of Russia’s most influential officials not only to identify Putin with the entire country, but also to tie Russia’s future to Putin’s personal continuity: “If there is Putin, there is Russia. Without Putin, there is no Russia”, Volodin said during a closed-door meeting in 2014.35

Volodin’s adulation of Putin – likely underpinned by his own aspirations for power – is one of the countless elements in Russia’s feedback loop: a system that has supported, amplified, and reinforced the central myth of Putin’s view of the West and Ukraine – a myth shaped both by Russian and Soviet imperial legacies, and by Putin’s personal experiences. It is precisely this state of mirrors that has transformed Putin’s individual quest for symbolic immortality into a collective Russian war against Ukraine – and has helped turn his idea of changing the past to “correct” the present into the brutal reality of an anti-Ukrainian genocidal endeavour.

This transformation was all but inevitable. As Putin’s regime hardened into deeper authoritarianism – especially after Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 – those around him who dared to suggest less radical paths in dealing with the West and Ukraine were steadily marginalised and silenced. In their place, more extremist voices rose, not just tolerated but ushered into the mainstream. By the time Russia launched its full-scale assault on Ukraine, Putin’s personal vision of the West and Ukraine had become the rhetorical bedrock: politicians and officials were permitted to be more extreme than Putin – but never, under any circumstances, less.

Putin’s real-world popadanstvo has relied on three major, overlapping and mutually reinforcing mechanisms: pan-Russian ultranationalism, historical revisionism, and dehumanising political technology.

The main amplifiers of Putin’s pan-Russian ultranationalism are the so-called siloviki – representatives of Russia’s armed ministries and security agencies. Putin himself is one of them, having come from the ranks of the KGB/FSB. Martin Kragh and Andreas Umland have explored the political ideas of the Russian siloviki, focusing on Nikolai Patrushev, who succeeded Putin as head of the FSB in 1999 and later served as Secretary of Russia’s powerful Security Council from 2008 to 2024.36

Patrushev fully shares with Putin the core mythological view of the West and Ukraine in relation to Russia: “In an attempt to suppress Russia, the Americans, using their proxies in Kiev, decided to create an antipode of our country, cynically choosing Ukraine for this purpose, trying to divide an essentially united [pan-Russian] nation. […] Speaking of denazification, our goal is to defeat the bridgehead of neo-Nazism created by Western efforts near our borders”.37 In other words, the West is seen as having forged the idea of a sovereign Ukraine into a fascist instrument of division and betrayal against Russia.

For Kragh and Umland, the viciousness of Patrushev’s anti-Ukrainian sentiments captures the characteristic posture of the siloviki – a stance rooted in the denial of Ukraine’s legitimate statehood, peoplehood, and leadership. By portraying Ukraine as a country gripped by fascism and Western subversion, Patrushev and his allies seek to explain how a nation they claim does not truly exist can nonetheless resist Russia’s assault. In the siloviki’s imagination, Ukrainians become enemies of Russia either by refusing to accept themselves as a mere branch of the Russian people, by collaborating with the West in its alleged war against Russia, or by doing both.38

In its turn, the mechanism of historical revisionism deepens the sacralisation of Russian history and infuses a sense of perpetuity into the idea of a Western conspiracy against Russia, with Ukraine portrayed as just one malign element among many.

Historical revisionism in Russia is largely channelled through the Russian Military Historical Society, headed by Putin’s aide and former Minister of Culture (2012-2020) Vladimir Medinsky, and through The Military Historical Journal, overseen by the Ministry of Defence. The Russian Military Historical Society floods the public sphere with patriotic fervour through multimedia exhibitions, monumental memorials, battle reenactments, military-historical tourism, and intensive work with children and young people.39 At its helm, Medinsky has become the chief architect of a state-driven, nationalist version of history, championing a singular “patriotic” narrative that exalts Russian greatness, defends Soviet-era myths, and casts Russia as both the eternal target of Western aggression and the steadfast bulwark against it.

As Andreas Heinemann-Grüder shows, The Military-Historical Journal also serves as a mouthpiece for a state-controlled, glorified vision of Russian and Soviet history, playing a central role in the broader project of memory politics – the reshaping of historical consciousness to suit present political needs.40 Its mission is to instil national pride through tales of Russian and Soviet heroism, especially on the battlefield.

In these narratives, Russia stands alone as the rightful moral heir to the Soviet Union’s victory in the “Great Patriotic War”, while other European nations are accused of falsifying history and whitewashing their alleged collaboration with Nazi Germany. At the same time, these myths fiercely deny any Soviet complicity in the outbreak of the war, erasing from memory the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the joint invasion of Poland in 1939.

Criticism of the Soviet Union’s collaboration with the Third Reich is presented as an attack on Russia’s honour and moral standing. Seen through this lens, the Russian war against Ukraine “appears as a defence of the ‘Great Victory’ in the Second World War, and thus rather as a holy war to defend the collective image of self than a war to achieve defined goals. The narrative is fundamentalised and essentialised, elevated to the status of a religious obligation”.41

As with the denial of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, Russia’s historical revisionism also seeks to erase evidence of its own culpability, particularly in relation to Ukraine. One of the most shameful examples of this practice is the deliberate suppression of the memory of around two hundred Ukrainian intellectual and cultural figures – writers, playwrights, scientists, and others – who were arrested on fabricated charges by Soviet security agencies and executed in the Sandarmokh forest in Karelia in 1937.42

Sergei Lebedev notes that the Sandarmokh executions expose a historical continuity in Moscow’s systematic violence against Ukrainian national identity, culture, and political autonomy. Acknowledging this legacy would compel Russia to confront its colonial and repressive past, to recognise the long-standing policy of suppressing Ukrainian (and other non-Russian) nationhood, and to undermine the narrative that Ukraine naturally belongs under Russian control.43

Since Russian historical revisionism imagines Russia as the perennial victim of Western aggression, events such as the Sandarmokh executions and the Nazi-Soviet occupation of Poland in 1939 must be erased from public memory – either by criminalising their discussion or by effacing the sites of remembrance.

Ultimately, Russian historical revisionism seeks to perfect the past by constructing a mythologised continuity of the “Great Russian” civilisation, whose integrity is portrayed as being constantly challenged, directly and indirectly, by the West. Today’s eliminationist war against Ukraine is held up as both the existential expression of Russia’s historical destiny and as the act that brings this mythologised past into reality. This creates a closed loop: sustaining the invented past demands violence, and violence, once unleashed, feeds back into the myth of the tripartite conflict in which the West uses Ukraine to harm Russia.

Pan-Russian ultranationalism and historical revisionism amplify the existing elements of Putin’s vision of the West and Ukraine. In turn, political technology reinforces that vision from a managerial perspective.

Contemporary Russian political technologists emerged in the 1990s; their role was to manipulate electoral campaigns in favour of those politicians who could afford to hire them. In this sense, they differed little from Western political operatives, consultants, and PR managers. But over time, emboldened by their domestic triumphs in steering public opinion, Russia’s political technologists evolved into something far more pernicious. Today, although many still serve politicians and officials, political technologists increasingly see themselves as a distinct managerial caste of social architects. They are guided by their own grim philosophy – one rooted in the belief that ordinary people are incapable of governing themselves and must be shaped, steered, and ruled from above to ensure the proper functioning of society.

In his discussion of the role of political technologists in Russia’s war against Ukraine, Andrew Wilson shows how their denial of individual agency has been translated into imperialist geopolitical directives.44 Drawing on the theory of the “Russian world” developed by Georgiy Shchedrovitsky, the concept of “supra-societies” formulated by Aleksandr Zinoviev, and Karl Schmitt’s notion of “Great Spaces”, political technologists such as Sergey Kiriyenko deny Ukraine any right to geopolitical self-determination. They argue that if the Russian elites – as representatives of a “supra-society” – so choose, the “Russian world” must be imposed on Ukraine, regardless of the will of its citizens, because Ukraine lacks the defining characteristics of a “Great Space”.45 After such an imposition, Ukrainians are to be reprogrammed and re-educated into Russians; those who fail to conform are to be exiled – or annihilated.46

Neither pan-Russian ultranationalism, nor historical revisionism, or political technology has introduced any qualitatively new elements into Putin’s intellectually shallow perspective on the role of the Ukrainian national project in the West’s perennial warfare against “Greater Russian” state. His understanding of that role had been shaped well before he started working in post-Soviet Russia. Yet his notion that an alternative history could be transformed into political reality might have remained little more than a fantasy without the enabling environment created by these three mechanisms, each amplifying and reinforcing the fever of his imagination. Whether the operators of these mechanisms share Putin’s visions of symbolic immortality, or whether they are – more likely – driven largely by financial gain and career ambition, they have become willing executors of his sick dream and equal accomplices in his inhuman crime.

The ruin

In 79 CE, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius annihilated several Roman settlements, most famously Pompeii and Herculaneum. In the 18th century, excavations at Herculaneum revealed the Villa of the Papyri, a treasure trove containing the largest collection of ancient texts to survive into the modern era, entombed beneath layers of ash and pumice. Hundreds of scrolls were unearthed – miraculously preserved yet carbonised, their fragile forms rendered unreadable, impossible even to unroll without inflicting fatal damage.

In 2023, computer scientist Brent Seales inaugurated the Vesuvius Challenge, an international contest aiming to recover the lost words of the Herculaneum scrolls.47 What was long deemed impossible has been made attainable by the strides of modern technology: today, scholars can peer inside the scrolls and read their contents without unrolling them.

The project unites minds across the realms of computer science, engineering, classical studies, papyrology, physics, and mathematics. It is a testament to the collective brilliance of humankind – a labour of hope and imagination, seeking to restore to humanity hundreds, perhaps thousands, of forgotten works of classical literature and philosophy.

The Vesuvius Challenge is not the first attempt to harness advanced techniques in service of this cause. However, it has proven the most successful effort so far, with just $1,500,000 awarded by 2025 – a modest price for revealing the first legible letters and titles from the Herculaneum scrolls, developing faster segmentation and ink detection methods, and creating open-source tools to advance the virtual unrolling and reading of ancient papyri.

The project is also a kind of time machine: its participants journey across the centuries, defying the wrath of Vesuvius to reclaim what its fires once wrested away, seemingly forever. In doing so, the project aspires to realise an alternative history – one in which the eruption of 79 CE had not consigned hundreds of ancient texts to oblivion.

It is in contemplating these awe-inspiring efforts devoted to the restoration of our lost ancient heritage that I feel a particular disgust toward the senseless devastation of valuable resources, and of invaluable human lives and futures, wrought by Russia’s eliminationist war against Ukraine.

And it is in observing the immense collective endeavour of Russian economists, propagandists, engineers, IT specialists, political technologists, educators, industrialists, infrastructure experts, and many others – all tirelessly working to fuel the relentless machine of death and destruction – that I cannot help but wonder:

What if, instead of extinguishing hope and future, instead of reversing life into death, their ingenuity – so capable of creating, persuading, and inspiring – were harnessed to reverse loss into renewal, and to craft a horizon shaped by dignity and human possibility?

***

An impressionable teenage Putin – a fan of historical reconstructions featuring Soviet operatives battling Western threats to Russia – marvelled, in his own words, at “how one man’s efforts could achieve what whole armies could not. One spy could decide the fate of thousands of people”.48 For Putin, his immersion in Soviet thrillers and identification with heroes such as Stierlitz became a rite of passage from adolescence into the adulthood in which he would become a KGB officer.

His years in the KGB only deepened his hostility toward the West, and toward any stirrings of popular sovereignty or national liberation – all of which, in defiance of Soviet repressive rule, he came to view through a securitised lens as deliberate assaults orchestrated by the West against Russia.

The trauma of Dresden in 1989 and the collapse of Soviet power appear to have taken Putin’s anti-Western prejudice to a new level, shattering the psychological armour that had shielded him from mortal dread with the promise of survival through the permanence of the Soviet state. As he grew more powerful as Russia’s president – and edged closer to death as a physical being – he must have increasingly seen the West’s victory in the Cold War, along with the existence of the Ukrainian national project, as historical ruptures that could be undone through war, reclaiming the promise of his symbolic immortality.

It took powerful networks of pan-Russian ultranationalism, historical revisionism, and dehumanising political technology to help Putin decide “the fate of thousands of people” and to forge the Russian war effort – directed openly against the Ukrainian nation and, indirectly, against the West. And it took millions of Russian soldiers and civilian auxiliaries to sustain it, turning ambition into brutal reality.

The war has already proved catastrophic not only for Ukraine, but for Russia as well. And in this, the true nature of Putin’s quest for immortality stands revealed: in the end, he has not achieved Russia’s greatness, but only ruin – the destruction of countless Ukrainian, Russian, and other lives, sacrificed like the retinue of a dying pharaoh to accompany him toward his inevitable final death.

Endnotes

-

- See the discussion of Russian popadanstvo in Eliot Borenstein, Unstuck in Time: On the Post-Soviet Uncanny (New York: Cornell University Press, 2024).

- See, for example, Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961); idem, Myth and Reality (New York: Harper & Row, 1963).

- David Crawford, Marcus Bensmann, “Putins frühe Jahre”, Correctiv, 30 July (2015), https://correctiv.org/aktuelles/korruption/system-putin/2015/07/30/putins-fruehe-jahre/.

- Andrew Wilson, Political Technology: The Globalisation of Political Manipulation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024).

- Ot pervogo litsa. Razgovory s Vladimirom Putinym (Moscow: Vagrius, 2000), pp. 71-72; Steven Lee Myers, The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (New York: Vintage Books, 2016).

- Arkady Ostrovsky, The Invention of Russia: The Rise of Putin and the Age of Fake News (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), p. 230; Phillip Knightley, The Second Oldest Profession: Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century (London: Pimlico, 2003), p. 368.

- In 2019, referring to a conversation with someone in the Russian Presidential Administration, Semyonov’s daughter, Olga Semyonova, said that Seventeen Moments of Spring was Putin’s favourite novel, see “Doch’ Yuliana Semyonova Olga o vospitanii ‘po Shtitlitsu’ i lyubimom geroe Putina”, Sputnik Belarus, 22 May (2019), https://sputnik.by/20190522/Doch-Yuliana-Semenova-vospitanii-po-Shtirlitsu-i-lyubimom-geroe-Putina-1041261512.html.

- “Romantik iz razvedki: v Peterburge vspomnili pervoe poyavlenie Putina na TV”, NTV, 27 March (2007), https://www.ntv.ru/novosti/106187/.

- Kirill Fokin, “A vas, Shtirlits, ya poproshu vmeshat’sya”, Novaya gazeta Evropa, 11 August (2023), https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2023/08/11/a-vas-shtirlits-ia-poproshu-vmeshatsia; see also “Chetyre portreta prezidenta-2000”, Kommersant, 11 May (1999), https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/15481.

- See Ivan Zassoursky, Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia (Armonk: ME Sharpe, 2004), pp. 132-134.

- A research report on the occupation of the Stasi district administration in Dresden and the period afterwards does not confirm Putin’s involvement in the standoff by the KGB residency on 5 December 1989, see Ilona Rau, “Besetzung der Dresdener Bezirksverwaltung und die Zeit danach – ein Recherchebericht”, StasiBesetzung, https://stasibesetzung.de/dresden/default-title.

- The 2006 German drama film The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen) directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck provides an excellent glimpse into the horror of the Stasi surveillance in East Germany.

- Ot pervogo litsa, pp. 71-72.

- “Annual Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation”, President of Russia, 25 April (2005), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/22931.

- “The Heroics of Everyday Life: A Theorist of Death Confronts His Own End. A Conversation with Ernest Becker by Sam Keen”, Psychology Today, Vol. 7 (1974), pp. 71-80 (71). See also Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (New York: Free Press, 1973).

- See Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, Thomas A. Pyszczynski, The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (London: Penguin Books, 2016).

- Holly A. McGregor, Jeff Greenberg, Jamie Arndt, Joel D. Lieberman, Sheldon Solomon, Linda Simon, Tom Pyszczynski, “Terror Management and Aggression: Evidence that Mortality Salience Motivates Aggression against Worldview-Threatening Others”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 74, No. 3 (1998), pp. 590-605.

- “Address by the President of the Russian Federation”, President of Russia, 24 February (2022), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843.

- Butkevych survived Russian captivity and was released in October 2024 as part of a prisoner swap between Ukraine and Russia. See also “Life After Captivity and Justice for Ukraine. Maksym Butkevych and Misha Glenny in Conversation”, Institute for Human Sciences, 19 March (2025), https://www.iwm.at/event/life-after-captivity-and-justice-for-ukraine.

- Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, President of Russia, 12 July (2021), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181.

- Yulian Semyonov, “Tretya karta”, Ogonyok, Nos. 37-52 (1975).

- “Helsinki Final Act”, OSCE, 1 August (1975), p. 5, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/5/c/39501.pdf.

- Ot pervogo litsa, p. 24.

- Mykola Riabchuk, “Ukrainians as Russia’s Negative ‘Other’: History Comes Full Circle”, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 49, No. 1 (2016), pp. 75-85 (77). Today, “khokhol” (singular) and “khokhly” (plural) are derogatory ethnic slurs used against Ukrainians.

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (New York: Knopf, 2004), p. 202.

- Zinoviev quoted in Lea Haro, “Entering a Theoretical Void: The Theory of Social Fascism and Stalinism in the German Communist Party”, Journal of Socialist Theory, Vol. 39, No. 4 (2011), pp. 563-582 (565).

- Haro, “Entering a Theoretical Void”, p. 581; Roger Griffin, Fascism: An Introduction to Comparative Fascist Studies (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), p. 15.

- Aron Brouwer, “Authoritarian Anti-Fascism in Russia: Embracing Fascist Symbols and Practices in the Name of Anti-Fascism”. Paper presented at the Fifth Convention of the International Association for Comparative Fascist Studies, “Beyond the Paranoid Style – Fascism, Radical Right and the Myth of Conspiracy”, held at the University of Florence, Italy, on 14-16 September 2022.

- Quoted in Griffin, Fascism, p. 16.

- The chorus of the “The Sacred War”, one of the most famous Soviet songs of the “Great Patriotic War”, read: “Let noble wrath boil over like a wave! This is the people’s war, a sacred war!”.

- See a helpful discussion of these developments, especially in the post-Sovet period, in Galia Ackerman, Le Régiment immortel: la guerre sacrée de Poutine (Paris: Premier Parallèle, 2019).

- “Signing of Treaties on Accession of Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics and Zaporozhye and Kherson Regions to Russia”, President of Russia, 30 September (2022), http://en.special.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/69465.

- Timofey Sergeytsev, “Chto Rossiya dolzhna sdelat’ s Ukrainoy”, RIA Novosti, 3 April (2022), https://ria.ru/20220403/ukraina-1781469605.html. See the English translation here: Timofey Sergeytsev, “What Should Russia Do with Ukraine?”, StopFake, 6 April (2022), https://www.stopfake.org/en/what-should-russia-do-with-ukraine-translation-of-a-propaganda-article-by-a-russian-publication-by.

- Andrey Pertsev, “Putin po familii Volodin”, Meduza, 7 April (2022), https://meduza.io/feature/2022/04/07/putin-po-familii-volodin.

- “Volodin: ‘Est’ Putin – est’ Rossiya, net Putina – net Rossii’”, MK, 23 October (2014), https://www.mk.ru/politics/2014/10/23/volodin-est-putin-est-rossiya-net-putina-net-rossii.html.

- Martin Kragh, Andreas Umland, “Ukrainophobic Imaginations of the Russian Siloviki: The Case of Nikolai Patrushev, 2014-2023”, Centre for Democratic Integrity, 6 October (2023), https://democratic-integrity.eu/ukrainophobic-imaginations-of-the-russian-siloviki/. See also Martin Kragh, Andreas Umland, “Putinism beyond Putin: The Political Ideas of Nikolai Patrushev and Sergei Naryshkin in 2006-20”, Post-Soviet Affairs, Vol. 39, No. 5 (2023), pp. 366-389.

- Ivan Egorov, “Patrushev: Zapad sozdal imperiyu lzhi, predpolagayushchuyu unichtozhenie Rossii”, RG, 26 April (2022), https://rg.ru/2022/04/26/patrushev-zapad-sozdal-imperiiu-lzhi-predpolagaiushchuiu-unichtozhenie-rossii.html. For stylistic purposes, I use the Romanised Russian, rather than Ukrainian, version of the name of Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv.

- Kragh, Umland, “Ukrainophobic Imaginations of the Russian Siloviki”.

- Dietmar Neutatz, “Putins Geschichtspolitikmaschine: Die Russländische Militärhistorische Gesellschaft”, Osteuropa, No. 12 (2022), 143-164.

- Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, “Memory, Myth, and Militarisation: Russia’s War Propaganda and the Construction of Legitimised Violence in Ukraine”, Centre for Democratic Integrity, 1 December (2024), https://democratic-integrity.eu/memory-myth-and-militarisation/.

- Ibid.

- Sergei Lebedev, “Sandarmokh, a Symbol of Russia’s Historical Responsibility for Colonial Violence against Ukraine”, Centre for Democratic Integrity, 14 November (2023), https://democratic-integrity.eu/sandarmokh/.

- Ibid.

- Andrew Wilson, “The Methodology of the ‘Russian World’ as the Technological Foundation for Ukrainophobia”, Centre for Democratic Integrity, 31 October (2023), https://democratic-integrity.eu/the-methodology-of-the-russian-world/.

- Ibid.

- Anton Shekhovtsov, “The Shocking Inspiration for Putin’s Atrocities in Ukraine”, Haaretz, 13 April (2022), http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2022-04-13/ty-article-opinion/the-shocking-inspiration-for-russias-atrocities-in-ukraine/00000180-5bd0-d718-afd9-dffc6b210000.

- Vesuvius Challenge, https://scrollprize.org.

- Ot pervogo litsa, p. 24.